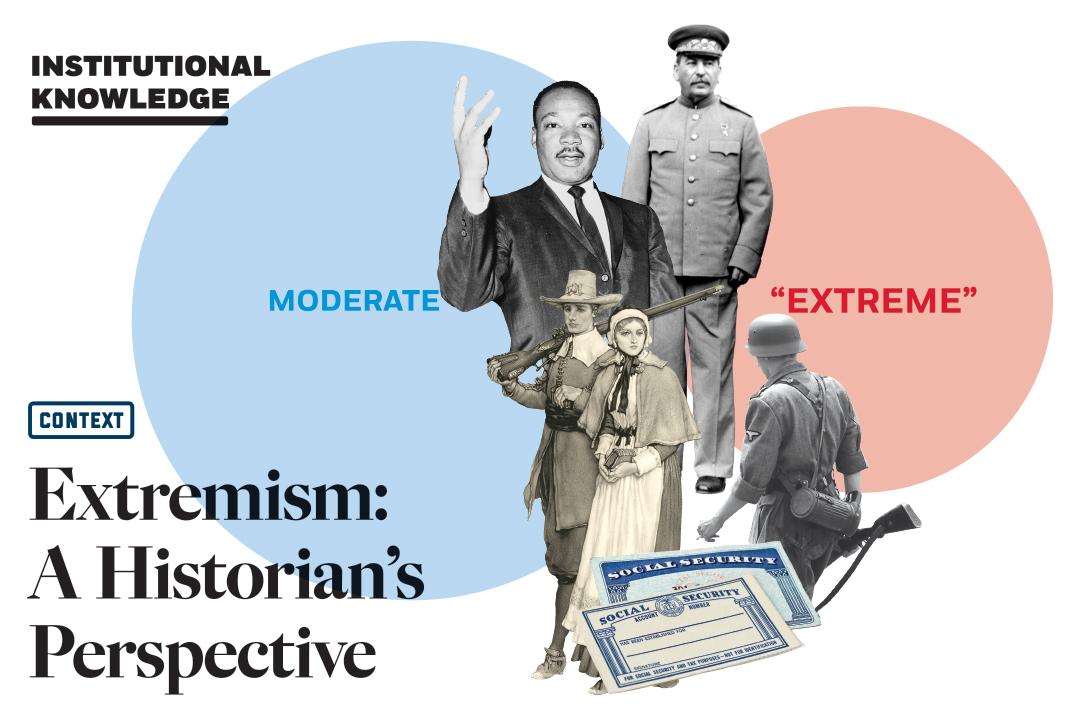

Extremism: A Historian's Perspective

(Social Security Cards: iStock.com/Richano / Soldier: iStock.com/Serhiy Divin / Others: Library of Congress)

Professor Leo Ribuffo talks about what we mean.

Leo Ribuffo, a GW professor of U.S. history since 1973, offers a note on the use of the word "extremism" in the United States.

From his perspective—the historian's perspective—"extremism" is a vague term for something that's not easily classified.

"On the one hand, Southern segregationists called Martin Luther King Jr. an extremist. Period," says Dr. Ribuffo, who got his PhD at Yale University in 1976 and is the Society of Cincinnati George Washington Distinguished Professor of History. "On the other hand, Joseph Stalin framed himself as a moderate beset by extremists on his right and left. Period. In fact, King was not extreme and Stalin was not moderate. Period."

Extremism is about context. Opinions change over time. The Puritans are stamped as extremists today, but in 1600s New England, most people agreed with them.

"Since it represented the majority," he says, "how can you call it an extreme movement?"

Opinions also change from place to place. In the United States, self-described Democratic- socialist Bernie Sanders may be extreme—break up the banks! free college and antibiotics for everyone!—but in Norway, he'd probably be a moderate.

Dr. Ribuffo says he's OK with "openly moralistic categories" like "bad, evil, stupid," but won't ascribe "extremist" to a person or concept. He'd actually like to retire the word altogether, especially as it relates to the U.S. political spectrum, which, since the 1930s, has been based on the correctness of whatever's considered the moderate position of the day and the demonization of the fringes.

"Probably the oldest political tactic anywhere—certainly the oldest political tactic in the United States—is to associate an opponent with his or her most disreputable or most peculiar allies," Dr. Ribuffo says.

The problem with that is the fringes move.

"It was very common for opponents of Social Security to say this is like Nazism or Communism," Dr. Ribuffo says. "'If the government gives you a number today to carry in your wallet, before you know it, you'll be in a concentration camp with the number tattooed on your arm.' Now, whether you like the Social Security system or not, almost everybody in retrospect would say that was an overreaction."

The language of extremism persists, Dr. Ribuffo says, because, historically, it's been an easy way to talk about something that's really hard.

"It's kind of a conceptual problem," Dr. Ribuffo says. "The real danger is that you write off people without trying to understand them. And if you're going to deal with people, even your enemies, it's better to understand them than not understand them. I mean, that's not rocket science."

Other Spring Features

5 Questions: Advocating for Syrian Refugees

Elliott School students launch the first collegiate branch of the Syrian refugee aid group No Lost Generation.

The Path to 'Mr. President'

An alumna and a professor discuss the first battle of a nascent Congress.

Ants That Don't Just Build Architecture, They Become It

In a new study, researchers explore the bridges that army ants build using their own bodies.