Ants That Don't Just Build Architecture, They Become It

(Photos and video: Courtesy of Matthew Lutz and Chris Reid)

In a new study, researchers explore the bridges

that army ants build using their own bodies.

A colony of the army ant Eciton hamatum can contain hundreds of thousands of ants. Those ants spend their days out looking for other ant nests to raid. When they find one, they fight, steal the larvae and carry the tasty spoils back to their young.

But army ants aren't just raiders. They're also architects, using their own bodies to make their trails faster and smoother. As they run, they cross over leaves, twigs, holes—and the bodies of their sisters.

"These self-assembling structures that army ants build are very unique in the ant world," says GW biology professor Scott Powell. Army ants plug potholes in the forest floor and build ladders to help the colony traverse tree trunks. They even build a temporary nest, complete with tunnels and rooms, that's reassembled every night by living ants who grab onto each other and hold on tight. Dr. Powell studied how the ants plug holes as a graduate student. Now he is part of a team of researchers trying to understand more about how army ants build one kind of structure: bridges.

The question, he says, is this: "How do you have these relatively simple, uninformed individuals that interact to solve a bigger problem?"

For a new study, Dr. Powell'sco-authors—Chris Reid, then a postdoctoral fellow at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, and Matthew Lutz, a PhD student at Princeton University—carried out experiments with colonies of army ants living on Barro Colorado Island, a Smithsonian research site in the Panama Canal.

The first step each day was to hike through the forest until they came across a column of foraging ants. Then Dr. Reid and Mr. Lutz had to coax the ants onto an experimental apparatus. Army ants move fast and pack a nasty sting. Poking them with sticks is a bad idea. Instead, the scientists used a trick they learned from Dr. Powell: spraying water from a plastic bottle to gently encourage the ants toward the ramp.

"Within about 10 or 15 minutes we had the ants already redirected through our maze and happily foraging, none the wiser that they were being experimented on," Dr. Reid says. Once on the apparatus, the ants were sent on a V-shaped detour, a pair of skinny plastic platforms connected by a hinge. In every experiment, the ants started a bridge at the joint between the two platforms—the pointy inner corner of the V-shape. Gradually, more ants would glom onto the outside edge of the bridge, which then inched away from the corner and back toward the line of the main trail.

The researchers found that the ants didn't always make the shortest possible route. Instead, they

adjusted the bridges constantly. When more ants were running through, the bridge moved farther to make a shorter route; when traffic let up, the bridge moved back toward the corner. The research was published in December in the Proceedings of theNational Academy of Sciences. The researchers developed mathematical models that suggest the ants are constantly managing the costs and benefits of the bridge. Bridges speed traffic, but tying up ants in bridges means risking having inadequate numbers at a battle.

For the next step, Dr. Powell and Simon Garnier of the New Jersey Institute of Technology, another author of the paper, hope to study more structures—and to collaborate with a group of researchers who work with a kind of simple robot that operates in swarms. Some day it might be possible to make robots that would assemble themselves into a bridge and adjust according to traffic, like the ants do.

"It's just a bunch of ants running around in the forest," Dr. Powell says, but it's also something else: "an extreme example of collective problem solving."

Other Spring Features

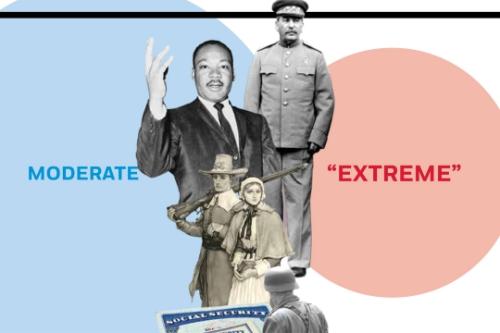

Extremism: A Historian's Perspective

Professor Leo Ribuffo talks about what we mean.

5 Questions: Advocating for Syrian Refugees

Elliott School students launch the first collegiate branch of the Syrian refugee aid group No Lost Generation.

5 Questions: Advocating for Syrian Refugees

An alumna and a professor discuss the first battle of a nascent Congress.