The Path to 'Mr. President'

Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon, MPhil ’06, PhD ’10 (Photo/William Atkins)

An alumna and a professor discuss the first battle of a nascent Congress.

By James Irwin

George Washington was on his way to New York in the spring of 1789 to take the oath of office as first president of the United States.

There was just one problem: Nobody knew what to call him once he got there.

"He's coming, the Senate is convening, and people start wondering: What are we going to call him?" Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon, MPhil '06, PhD '10, said at an event in February. "Are we just going to call him 'Mister?' I don't think so."

This confusion, she said, led to the first dispute between the Senate and the House of Representatives, the topic of Dr. Bartoloni- Tuazon's 2014 book, For Fear of an Elective King. She explored the topic in discussion with Associate Professor of History Denver Brunsman, part of the university's monthlong celebration of Washington's life.

The idea of the presidency was contentious at the time, she said.

"We had just fought a war against a king, and yet, six years after the end of the war, this new Constitution featured a federal, singular, central executive with no term limits and vaguely defined powers," she said. "There were those who were worried that the president would turn into a despotic, all-powerful monarch. But there was another group of Americans who were worried about a weak executive that would be subject to manipulation."

Those fears framed a congressional (and later public) debate in April and May of 1789 over whether to add a regal prologue—"elective majesty" for example—to the title "president of the United States." The Senate wanted the title. The House was against it. Washington's own celebrity played a role in shaping positions.

"The enthusiasms toward Washington were so excessive and king-like," Dr. Bartoloni- Tuazon said. "He brought this whiff of monarchy to the presidency just in the way people celebrated him. And that was a problem for the office."

Vice President John Adams, who led the pro-title movement, feared the rise of an aristocracy that would corrupt and diminish the presidency, Dr. Brunsman said. He believed the Senate could become such a body if the executive was too weak. A powerful title with royal overtones would strengthen the office. The House and its effective leader, James Madison—and, to an extent, Washington himself—were on the other side of the debate. Article II of the Constitution called the officeholder "president." The House saw no reason to deviate.

After three weeks, the Senate yielded to the House. It was a win for civil discourse—and for the presidency, Dr. Bartoloni-Tuazon said. Debate, meanwhile, slowly moved into the streets and newspapers of the new country, where the public took up the argument that summer. A majority believed the Senate was right to drop the pro-title fight. Though they were debating something that was legislatively finished, it was an important moment, Dr. Bartoloni-Tuazon said.

"The public needed to debate this," she said. "As a result, some public fears—about their new government, Congress and their new president—were resolved. They gained more trust in the new federal government, that these new legislators could argue something as politically volatile as this and come up with the solution the people agreed with."

Other Spring Features

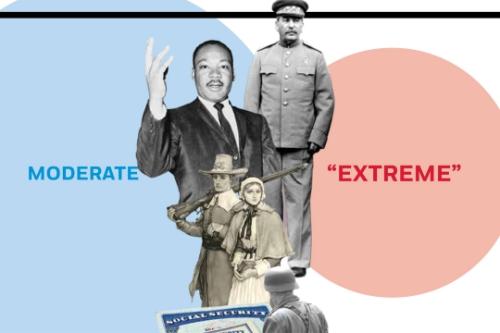

Extremism: A Historian's Perspective

Professor Leo Ribuffo talks about what we mean.

5 Questions: Advocating for Syrian Refugees

Elliott School students launch the first collegiate branch of the Syrian refugee aid group No Lost Generation.

Ants That Don't Just Build Architecture, They Become It

In a new study, researchers explore the bridges that army ants build using their own bodies.