Balancing the Books (Spring 2016)

Alumna Kyle Zimmer’s nonprofit, First Book, is pooling the

buying power of educators and families in need to

change the face of—and the access to—children’s publishing.

By Julyssa Lopez

Photos by Logan Werlinger

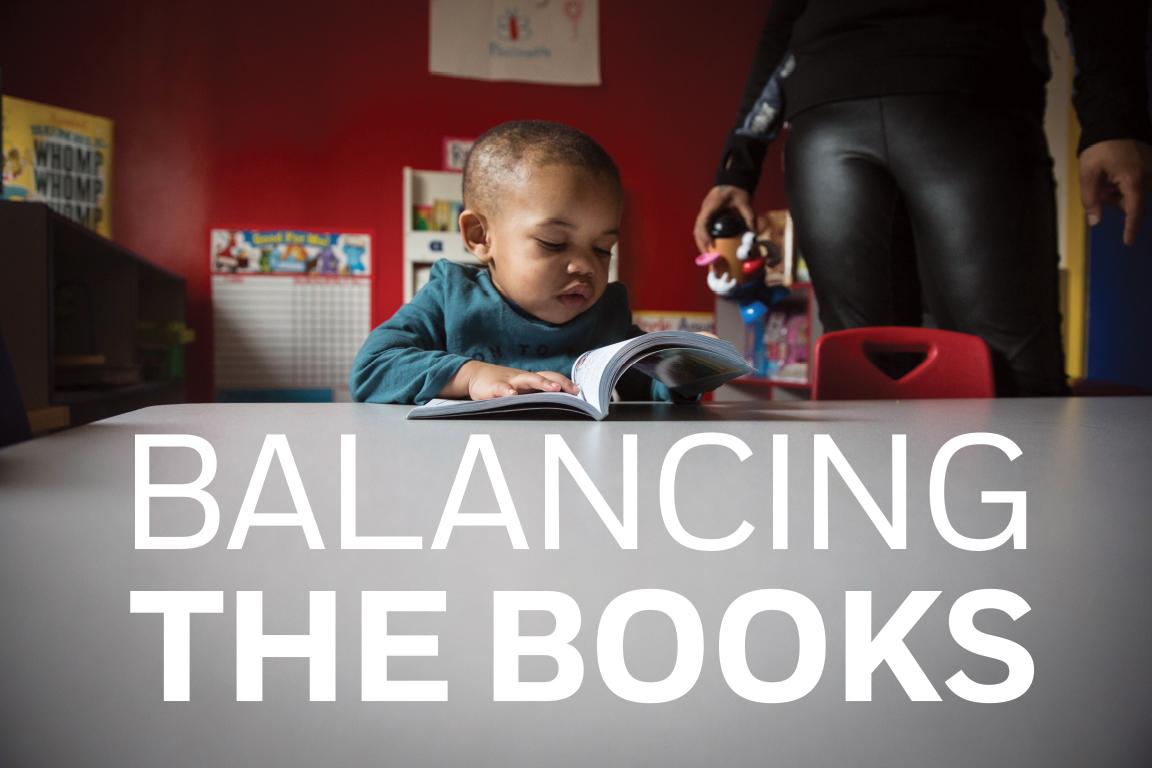

The two-floor apartment in Woodland is loaded with crates of glossy new children's books.

Books are a rarity in this Southeast D.C. neighborhood. Woodland is located in one of the city's poorest and least-developed wards. The neighborhood is small, home to about only 600 people, nearly all African American. Crime and gang violence are frequent here—last summer, police flooded the streets after the community witnessed three shootings in just 10 days.

Cherie Craft is straightening up the piles of hardcovers. She came to Woodland two years ago to open an outpost of Smart from the Start, a community organization that started in Boston to encourage early learning for children growing up in low-income communities. The kids in Woodland know that they can get free books through her—they constantly poke their heads into the blue mailbox outside to see if she has slipped in any new volumes.

Today, she has about 100 copies of Raquel Jaramillo's award-winning Wonder and Disney's bubble gum-pink P Is for Princess, among others. The stacks of books could fill a small library.

"Who's that?" Ms.Craft says, pointing to the little boy in the book.

"Me," Blake replies.

"Look at this," Ms. Craft says, flipping over a book in her hands and pointing to the $12.99 price on the back. "We would never, ever be able to afford this." She doesn't have to—a Washington organization called First Book, co-founded and run by Kyle Zimmer, JD '87, stocks schools, caregivers and community programs like Ms. Craft's with free and low-cost books; 140 million of them, actually, and counting.

Ms. Craft is particularly excited this afternoon because First Book shipped over Jean Reagan's How to Surprise a Dad. She says it's a favorite among the young fathers in Woodland, who come to Smart from the Start for parenting workshops.

"First Book knows exactly the kinds of books we like," she says. "To read a book about a dad playing and doing things with his kids makes a huge difference around here."

As she's speaking, 2-year-old Blake Augburn bounds into the room with the self-assuredness of a Fortune 100 CEO—like he owns the place.

"He does own the place," Ms. Craft laughs.

Blake has been coming to Smart from the Start with his parents since he was a newborn. Blake's father, Ed, is one of the young dads Ms. Craft works with, and one of the first people she connected with when the center opened. In the corner of the room, a rocking horse waits for Blake to hop on for a ride. Blake approaches the candy-colored steed, plays equestrian for about 10 seconds and then abruptly dismounts. He runs to the table where Ms. Craft put down a copy of How to Surprise a Dad.

"Book!" he shouts.

He reaches for it and thumbs through pages of illustrations by Lee Wildish, which tell the story of two African American kids.

"Who's that?" Ms. Craft says, pointing at the little boy in the book.

"Me," Blake replies.

"What about that?" she asks, pointing to the father in the book.

"That's Daddy," he says. The room releases a collective "Aww."

The scene is cute. It's endearing. It would make anyone smile. But there's more behind this moment—nearly 25 years and an organization that has been working relentlessly to shake things up in the world of children's literature.

That's the story of First Book, the nonprofit that is working with thousands of organizations like Smart from the Start to bring diverse stories to kids like Blake, and, in the process, it's going where no one in the publishing industry has gone before.

Cherie Craft’s Woodland outpost of Smart from the Start receives books from First Book; kids constantly check in to see which books have arrived.

First Book's offices are tucked between a handful of restaurants and stores downtown, across the street from the National Press Club and a few blocks from the White House. The 80-person organization rents four floors in a stone building with gilded trimmings. While First Book deals in nonprofit work, the space has the creative, playful nature of a startup. The senior vice president of finance sits in a desk he crafted entirely from books. The customer service team answers calls beneath streamers and the glow of Christmas lights. The stairwell linking the floors is covered in murals.

It feels animated and buzzy—not unlike Ms. Zimmer, 55, the alumna who is First Book's president, CEO and co-founder. She is a recognized force in these halls and beyond: In 2014, the National Book Foundation presented her work with its annual Literarian Award, an honor previously given to Maya Angelou and Terry Gross.

She's a petite woman, humble about her own accomplishments but completely enthusiastic about the goals of First Book. She's upbeat, and she speaks authoritatively and directly, which might come from her years working in corporate law. Her demeanor is something the publishing industry talks about.

"The first thing that struck me about her was that she was a very motivating, energized, passionate person," says Susan Katz, who retired last year as president and publisher of HarperCollins Children's Books. "Kyle was a woman on a mission."

That mission began more than 25 years ago when Ms. Zimmer was working as a lawyer. She spent time then volunteering at Martha's Table, an organization that serves a large number of D.C. children who are homeless or underprivileged. She would sit in a barren room, trying to tutor the kids and help them with homework.

"There would be 50 or 60 kids, doing everything right. They were looking for adult intervention.

They were looking for a safe place," Ms. Zimmer recalls.

She remembers thinking, "These hours would really be so much more valuable to these kids if we just had books."

But Martha's Table couldn't afford books. Neither could most of the children's families. Ms. Zimmer grew up in a household that valued social justice and public service. As a lawyer, she had represented the interests of the Navajo Nation and worked for an organization founded by longtime consumer safety advocate Joan Claybrook.

She began to think about how to provide more books and educational resources to the kids she saw every week.

Starting a nonprofit was in the back of her mind early on. She had frequent conversations with her friend Elizabeth Arky, JD '86. But to build the boundless repository that First Book would turn out to be, Ms. Zimmer first would need to learn the ins and outs of the publishing industry.

Lesson number one: To a publisher, every book is a risk.

The industry is based on a consignment model, Ms. Zimmer explains, and publishers have to front the money for all the retail books they produce. Books that collect dust on a store shelf become unsold inventory and they're shipped back to publishing houses, which absorb the cost.

Publishers factor the cost of that returned inventory into their prices, which, in part, is why you'll often see hardcover children's books heaving an $18 retail sticker. If you're one of the estimated 31.4 million U.S. children living in a low-income family, that price is a nonstarter.

Lesson number two: Since publishers need to ensure they sell a certain amount of books, they produce titles that appeal to people who can buy them. Those people, unsurprisingly, are affluent. They are also predominantly Caucasian, and the stories told in the pages of a picture book often reflect that.

"This isn't about black or white—the dominant color in this conversation is green," Ms. Zimmer says. "I think if you went to a publisher and could prove that books about purple people would sell, publishers would climb over each other to produce them. These are businesses."

It was that kind of acumen that set up First Book to be a partner to publishers, not an adversary.

Ms. Zimmer and Ms. Arky pitched their idea to friend and fellow lawyer Peter Gold. The three made plans to talk more about the challenges of the publishing industry and come up with some solutions over a meal together. A successful dinner might end with a good conversation and some podcast recommendations.

This one ended with an outline for building a social enterprise.

First Book President and CEO Kyle Zimmer, JD ’87, cofounded the nonprofit in 1992 with Elizabeth Arky, JD ’86, and Peter Gold. Both Ms. Arky and Mr. Gold still serve on its board of directors, as they have from the beginning.

One of the most distinctive qualities about First Book is its plucky approach to innovation. Its ethos is similar to the "fail fast" mentality prevalent in Silicon Valley: If a strategy doesn't work, scrap it and learn from it. Then think of something better.

After experimenting with a volunteer-based distribution model, the First Book team came up with the idea of the National Book Bank. Unsold children's books, cheerful illustrations and all, eventually get pulped into a cloudy liquid used for recycled paper. First Book's team realized they could save books from that end by creating an efficient avenue for publishers to donate excess inventory to North American schools and community programs serving children in need.

The result is the first and only clearinghouse for large-scale book donations, which launched in 1998. Through the National Book Bank alone, First Book now distributes approximately 10 million books each year from 19 warehouses around the country.

But, Ms. Zimmer says, the Book Bank alone wouldn't close the gap between the publishing industry and the base of the economic pyramid. The bank opened access to free books, but not to the ones flying off the shelves at stores. And because the Book Bank depended on donations, First Book couldn't predict what titles would be available at a given time. Ms. Zimmer wanted teachers and kids to have a chance to access the industry's best, and to know the titles they need will be available when they need them.

So in 2008, the team set up an e-commerce site, the First Book Marketplace, specifically for those serving children in need.

First Book arranged to buy large quantities of new titles from publishers. By guaranteeing that inventory would not be returned, First Book could negotiate lower prices and offer books to educators at 50 percent to 90 percent below retail.

"This isn't about black or white -the dominant color in the conversation is green."

From the start, Ms. Zimmer knew this would only work if First Book could allay publishers' concerns about an alternate market. So the organization set up a screening process: Anyone who wanted books would register through First Book and submit their bona fides. First Book would review every request.

"They were very market-driven and they wanted to know our needs," Susan Katz from HarperCollins remembered. "That—and that they were so dedicated to providing diverse books—made them easy to work with."

With publishers on board, the Marketplace began attracting a staggering range of people and organizations that worked with children. Requests came in from teachers who were opening their own wallets to fill classroom bookshelves, librarians wanting to replace tattered paperbacks, even barbershop owners who opened their doors to kids who had nowhere else to go after school.

"Literally anywhere where kids gathered and where kids were reading—or, in most cases, not reading," Ms. Zimmer says. The Marketplace evolved. It soon offered thousands of books (recently, it added snacks, school supplies and even coats). The membership roster of schools and programs grew with it. Between the National Book Bank and the Marketplace, the list hit 50,000 members, then 100,000.

And teachers and nonprofit workers didn't just ask for resources and walk away. They had questions and requests. They had ideas. What started as a screening device became a powerful feedback loop, for the first time aggregating a significant number of the 1.3 million educators that the organization estimates serve kids in need.

First Book began to realize its roster was more than a list of names: It was market muscle and it could be flexed.

Then a little larva with an appetite came along.

When network members repeatedly complained that they would need to buy both an English and a Spanish version of Eric Carle's 1969 classic, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, to serve the needs of their classrooms, First Book decided to test its heft.

The organization reached out to Philomel Books, a children's literature imprint of Penguin Books USA, with a proposition: If Philomel produced a bilingual edition of the book, First Book would buy 30,000 copies to sell on its Marketplace. With a guarantee that high, Philomel agreed and published the book in May 2011.

Ms. Zimmer was floored.

"Oh my God," she thought. "We could do things that have a splash effect in the larger market."

For First Book's next act, the organization set out to address the lack of diversity in children's books head-on.

Again and again First Book heard that the network wanted books that illustrate the experiences of their kids. According to a tally of 3,400 kids' books reviewed last year by the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, only 7.8 percent had a significant character or subject representing African Americans, and for Latinos it was just 2.4 percent.

This would be trickier than stocking libraries and classrooms, or sparking a special run of one book. First Book would need to prove it had enough influence and buying power to fund a change. The organization was by now partially self-funded from revenues from the Marketplace, and it had financial support from foundations, corporate partners and others. Plus, now it had a network of hundreds of thousands of educators behind it.

In 2013, the organization approached publishers with an offer: First Book would put down $500,000 to buy books from the publishing house that submitted the best selection of existing titles featuring minority voices, characters of color and diverse experiences. Publishers responded enthusiastically. And this time, Ms. Zimmer wasn't surprised. "This is not a group of people who are recalcitrant. Publishers want to make this happen.

It wasn't shaming the publishers—we were saying we have a market, and we can make it so publishers are less nervous about stepping out into uncertain territory," she says. First Book was so inundated with proposals that it became hard to choose a single winner. It decided to choose two—Harper-Collins and Lee & Low Books—and double its $500,000 commitment.

The "big buy," as First Book calls it, launched the start of its market-driven Stories for All Project, made media headlines and brought to the First Book Marketplace more than 600 existing titles featuring diverse characters and experiences.

Its expansion into this new realm only boosted growth: The membership roster now stands at more than 230,000 and the Marketplace sells 5 million low-cost books each year, on top of the 10 million that are given away by the Book Bank.

And as for that first test of its market muscle? First Book has sold more than 140,000 copies of the bilingual version of The Very Hungry Caterpillar and inspired Penguin to make the edition available in retail stores.

Alison Morris' office resembles what a library might look like after an earthquake. Every couple of feet a new stack of books sprouts from the floor. The middle row of a blond wood shelf has collapsed under the weight of colorful volumes.

And yet, it doesn't feel chaotic. That might be because Ms. Morris herself is neat and organized in her thinking, and has a tidy catalog of children's books built in her head. She's read almost every text in the room.

As the senior director of First Book's collection development and merchandising team, Ms. Morris is the person who scours through journals and publisher catalogs. Her goal is to expand the Marketplace with materials that speak to the children First Book serves. Questionnaires and surveys of First Book's network have helped paint a picture of those children. Forty-five percent of respondents report that the kids they serve face homelessness.

Eighty-three percent say their students come from single-parent homes. Thirty-two percent say their kids encounter community or gang violence. Fifty-four percent report that the kids they serve have incarcerated parents or siblings.

Ms. Morris thinks about these things constantly when she's introducing new titles to the Marketplace. She goes to a bookshelf outside her office and comes back with a copy of Jacqueline Woodson's Visiting Day. The picture book follows a young girl excited about reuniting with her father, who is in prison. The story doesn't dwell on why he's incarcerated. Instead, it focuses on the child's relationship with her dad and the strength of their bond.

Another one of her favorite new books is K.A. Holt's House Arrest. The novel, written in verse, describes a young boy's year on probation after he uses a stolen credit card to help his family.

"I don't think books are intended only for a certain kind of kid," she says. "Any kid can read this and it will help them develop empathy and help them ponder their sense of right and wrong."

But when these books go into the hands of kids living these experiences, she says, they become personal.

The idea has continued to drive the organization's Stories for All Project. Last year, the Walt Disney Co. helped First Book distribute more than 270,000 culturally relevant books to the Latino community. First Book also worked with HarperCollins to release an English and Spanish bilingual edition of Goodnight Moon.

More recently, working with Target, Jet- Blue and KPMG, First Book brought to its Marketplace 60,000

copies of six more books with diverse characters or plots. Two of those titles are from authors and illustrators new to the children's picture book world: Boats for Papa, Jessixa Bagley's story about dealing with the loss of a parent, and Emmanuel's Dream, Laurie Ann Thompson's true account of disabled cyclist Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah. Four were existing titles made available in exclusive paperback editions, including And Tango Makes Three about a same-sex family, and Niño Wrestles the World about a little lucha libre fighter.

In February, the White House, First Book, the New York Public Library, publishers and other libraries launched an effort to provide access to $250 million worth of e-books for free to children from low-income families. And this spring, the Library of Congress recognized First Book with its $150,000 David M. Rubenstein Prize, part of the library's annual Literacy Awards.

Still, lofty goals remain. Ms. Zimmer says the market-driven strategies for the Stories for All Project will continue to evolve, and that First Book is expanding its presence in Canada and the United States, aiming to reach "every educator who needs us and every child who needs us." First Book also has small pilot projects in 19 countries to figure out how it can scale its distribution internationally.

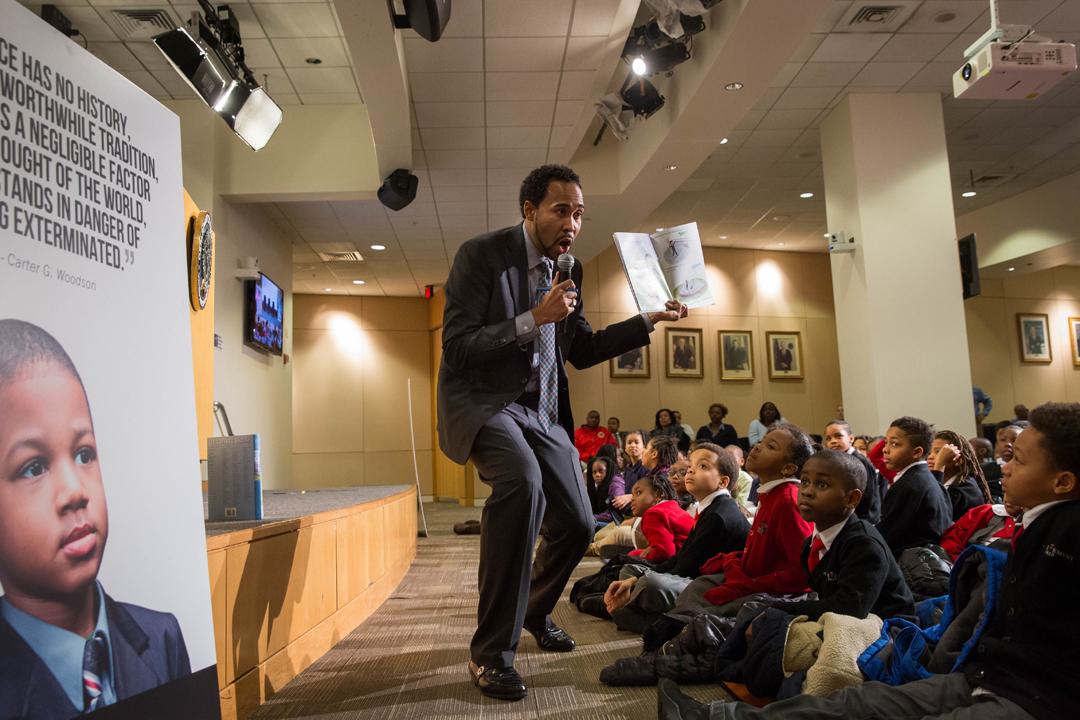

On a Monday morning in February, lopsided lines of elementary school kids file into the Department of Education's auditorium. It isn't the sterile government building room you might imagine; the lighting is bright and the carpets are colorful and playful. There's music. The floor is decked out with a couple of football-shaped beanbag chairs that the kids race toward excitedly.

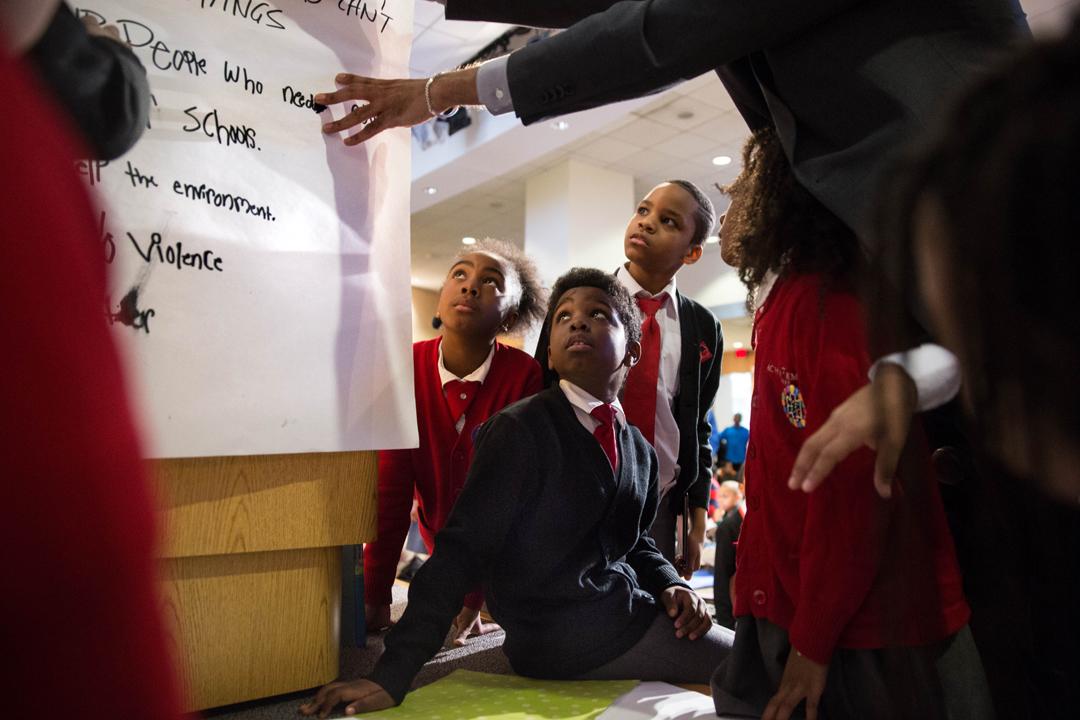

Five inner-city D.C. schools have been invited here for a Black History Month celebration hosted by First Book and the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans. The White House initiative has planned a couple of empowerment activities for the kids, and then First Book will give every child a hardcover copy of the anthology Our White House: Looking In, Looking Out.

A room full of kids spanning grades three through six might sound like a recipe for chaos. Yet the students are surprisingly quiet and attentive. They sit cross-legged watching little screens blaring videos of YouTube sensation Kid President.

The initiative's executive director, David J. Johns, takes the mic and kicks off the action. He's tall and enthusiastic, comfortable talking to elementary school-aged kids. He's been a teacher before, and he's been spearheading educational excellence for African American students since former Education Secretary Arne Duncan put him in charge of the initiative in 2013.

He pulls out a copy of Catherine Stier's If I Were the President and begins reading it out loud. The book follows a multicultural cast of kids imagining what it would be like to lead the country.

"If I were president," Mr. Johns reads, "I'd travel in my own limousine or my private airplane, Air Force One." He looks up at the crowd of students, and they're hooked. He decides to intersperse the story with some trivia.

"Do you guys want to know what the code name is for the president's car?" Mr. Johns asks. Heads bob up and down in unison. "The Beast," he whispers, letting everyone in on the secret. Two boys exchange wideeyed looks and one repeats the name: "The Beast!"

When Mr. Johns gets to the last page of the book, he breaks the kids into groups and gives them an assignment to come up with a list of what they would accomplish as president. Students gather around large sheets of paper to brainstorm ideas that range from "treat everyone equal" to "make college free." After every group presents its platform, First Book's staff begins lining up the kids in front of a massive table where their free books are waiting. One by one, Our White House: Looking In, Looking Out gets placed into every pair of small hands. Some of the kids are so little they have to hug the weighty, 250-page hardcover with both arms.

A few teachers linger in the auditorium, asking their classes to pose for pictures. Clusters of students hold up their White House books before a constellation of flashing iPhone cameras. They grin up into the lenses, showing smiles with missing baby teeth. The phones come down, and a couple kids peel away from the crowd.

One child plops down in the middle of the floor and lurches the book onto his lap. He begins thumbing through it slowly, looking at illustrations of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. He lands on a picture of the White House.

After a day like today, where he's spent all day thinking about what he would do as president, he might be picturing himself in that house.

Next to him, a couple of other children have also stopped to look inside the book. The room has grown quiet—just a few voices and the sound of pages turning.

Other Spring Features

Tracking Terror in the U.S.

A new think tank finds the "democratization of terrorist recruitment" on social media is helping to create an increasingly diverse picture of Islamic-inspired extremism.

In Addition to History

Novelist Thomas Mallon imagines what lies between the facts in the lives of presidents and those around them.