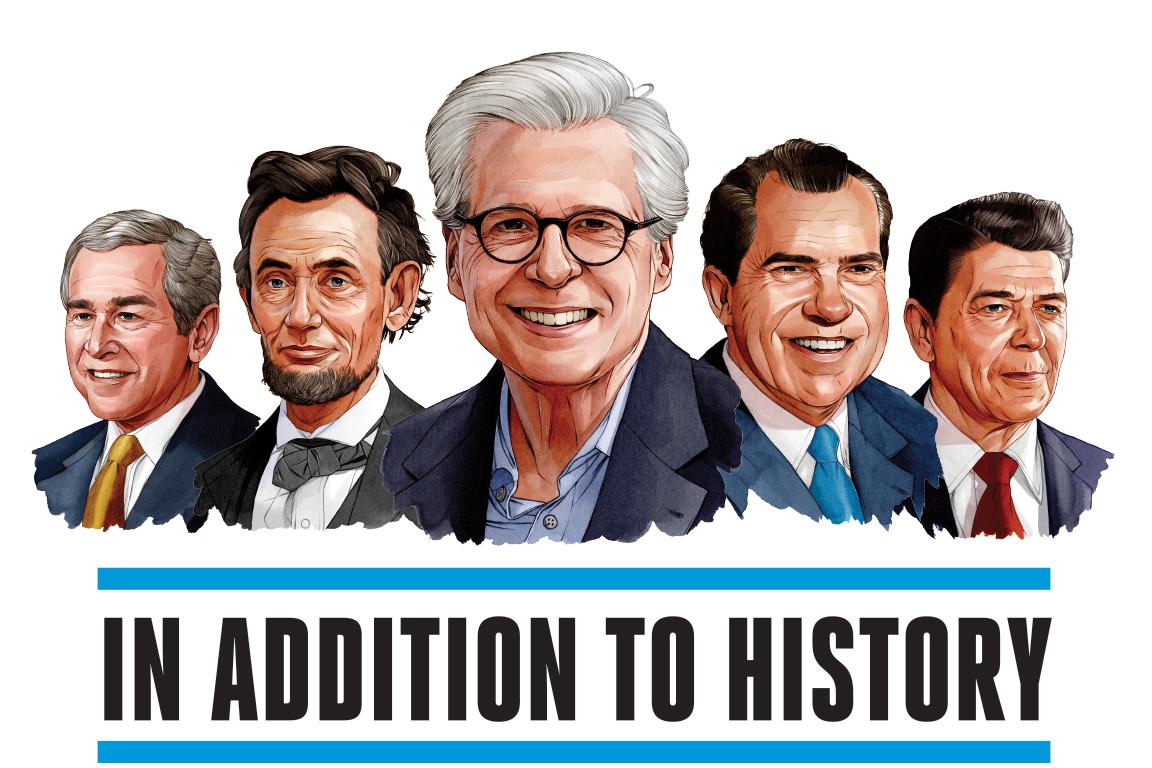

In Addition to History (Spring 2016)

Novelist Thomas Mallon imagines what lies between the

facts in the lives of presidents and those around them.

By Matthew Stoss

Illustrations by Michael Hoeweler

The best part about Thomas Mallon's 2009 takedown of Ayn Rand—a delicate evisceration, massaged over 4,226 words in a November edition of The New Yorker and executed with the precision of a GPS-enabled scalpel—is how much he earned it. The dear man forfeited a summer to endure all 9 billion pages (approximately) of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, and other Randian writings, as well, in the holy name of preparation.

Dr. Mallon is nothing if not a thorough man, tidy and prone to cardigans, cleanliness and teal-striped socks. A registered (but wholly disenchanted) Republican, the 64-year-old gets his hair cut for $26 at the Watergate barbershop, because, well, if it's good enough for Bob Dole, he says, it's good enough for him. It's also a short walk—he might ride his Marin bicycle if it was much farther—from his sixth-floor Phillips Hall office in Foggy Bottom, where he's been an English professor and Rate My Professor darling since 2007.

Students vouch, with an average of 4.8 stars out of 5, for his charm, his wit, his helpfulness, his clarity.

They testify, as even Ms. Rand might, if she were still alive, to his dedication to knowing as much stuff as possible, and then, if there's time, a little more. An essayist, a critic and a well-lauded novelist, Dr. Mallon—who got his PhD in English and American literature from Harvard University in 1978—researches hard and at length, which is how he came to write about Ms. Rand, her philosophy of Objectivism and what she watched on TV.

Before that New Yorker piece, Dr. Mallon hadn't had more than a casual brush with Ayn Rand. He might have been among that group that, as he wrote seven years ago, made "their first and last trip to Galt's Gulch ... sometime between leaving Middle-earth and packing for college." And he went back only because The New Yorker paid him to write about two Rand biographies: Ayn Rand and the World She Made, by Anne C. Heller, and Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, by Jennifer Burns.

Dr. Mallon, though, went into the dark beyond the biographies, also trudging—uphill (both ways), barefoot, in the snow—through Ms. Rand's novels, We the Living, The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, and Ms. Rand's nonfiction, The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature and The Art of Fiction: A Guide for

Writers and Readers. Dr. Mallon whittled from a block of Randian ironwood an essay that went deep on her Russian roots and a screenwriting dalliance in Hollywood. Dr. Mallon dug into Ms. Rand's personal life, her political influence and her cult of votaries. He even mined Ms. Rand's Charlie's Angels fandom for a mordant crack about Objectivism.

In total, Dr. Mallon persevered through more than 3,500 pages of Ayn Rand and Ayn Rand scholarship to craft a review-essay on two biographies, to establish gravitas and earn these delicious cuts: Ms. Rand's "intellectual genre fiction puts her in the crackpot pantheon of L. Frank Baum and L. Ron Hubbard," "the novel's dialogue is never even accidentally plausible" and "the books would have been no more concise and no less clumsy

had she written them in Russian."

Ariel Gonzalez—an English professor at Miami Dade College and NPR host who has reviewed books for The Washington Post and The Miami Herald—described Dr. Mallon as one of the "best book critics" in the country because, while Dr. Mallon may not celebrate an author's catalog, he will most certainly read it, even if it's "so bad," Dr. Mallon says, it "just makes my head explode."

"He writes comprehensive essay-reviews on someone," Mr. Gonzalez says. "That's something a lot of critics won't do. He takes the author seriously. So even if he's criticizing you—even if he's attacking you—you should at least be happy with the fact that he's paid so much attention to your work."

That is what he did for 4,226 words on two Ayn Rand biographies. Now, consider what he might do for his own books.

THOMAS MALLON PULLED, from the fluorescent hammerspace of his corner office, the first four pages of Landfall, his novel about President George W. Bush. Dr. Mallon's 10th novel, it's scheduled for a 2018 release and with a chunk of it set during Hurricane Katrina. Landfall is the final book of the "trilogy" he never meant to write, but Pantheon Books, his publisher since 1997, and his agent suggested he postpone a novel centering on Fort Sumter during the Civil War—tentatively titled The Late Unpleasantness—to first novelize Bush the Younger.

The "trilogy"—Dr. Mallon didn't name it that but he likes to use the term ironically—covers the major Republican presidents from the last third of the 20th century and the forward tip of the 21st. The series started with Richard Nixon and the PEN/Faulkner-nominated Watergate in 2012, then Ronald Reagan and the well-received Finale: A Novel of the Reagan Years in 2015, and now, W. and Landfall.

"You are the first person to read that, besides me," says Dr. Mallon, handing over the pages. "It was only written in the last couple of days."

It's January and the air is gloomy. The pages are handwritten front and back in blue roller-ball ink, ripped primly from legal pads he buys in quantity. Dr. Mallon's handwriting is small, more print than cursive—but occasionally the two modes do commingle—the letters snuggled. No one would teach children to write this way. There are big spaces between the words and he writes on every other line to leave optimum room for editing, which is where Dr. Mallon does his hardest work.

There's nothing spontaneous about Dr. Mallon's process, no word-magic, no jazz, and if there's a stream of consciousness, it's been dammed. He would never self-oblige himself an artist—how gauche—and it's still modestly that he marks "writer" on his W-2.

"I said once in an interview, and I got in trouble for it—it was thrown back in my face by a critic, later, who didn't like something I'd written," Dr. Mallon says. "I once said that I never think of myself as an artist; I think of myself as a craftsman."

He thinks for a moment, an Orwellian Barry Goldwater campaign poster staring down his back from the skinny far wall of his office.

"I suppose I am an artist if I've written all these novels and they've been taken pretty seriously and so forth," says Dr. Mallon, whose mastery of historical fiction has been compared to that of Gore Vidal, with whom Dr. Mallon worked as an editor at GQ in the early 1990s.

Dr. Mallon even modeled Finale on Mr. Vidal's Lincoln. In both novels, neither Reagan nor Lincoln are point-of-view characters. Instead, they're observed Guildenstern and Rosencrantz-style by the people in the near periphery—William Seward and Nancy Reagan. She, along with Richard Nixon and Christopher Hitchens (a real-life friend of Dr. Mallon's), are the stars of Finale.

"I think of them as being more like carpentry or architecture, actually," Dr. Mallon says of his novels. "Obviously, they've got an inventive element to them, so there's the architectural aspect to them, but maybe it's just because I enjoy it more—the carpentry of them, the rewriting of them.

"I don't know why, this interviewer—this was quite a long time ago—he seemed repelled by the notion that a literary novelist wouldn't think of himself as an artist. Who confers that title on himself? I'm an artist. I can remember the point in my life when, after a couple of books, I could actually—when people asked me what I did—I'd say I'm a writer, even though ... I was a working college professor, like I am now. And I thought, 'I'm entitled to that—I'm entitled to that self-description.' ... I take 'writer' as my primary identity, and that I'm willing to claim. Artist is maybe a bridge too far."

There would be more boxes in Dr. Mallon's office but he's just moved in from across the sixth-floor elevator bank and a lot of his stuff hasn't made the trip. He's also been shipping the accumulated clutter of a book-writing career that started at age 31 to Brown University, which, since 1991, has been compiling a Mallon archive that now fills 16 boxes and spans 15 linear feet in the key-swipe-secured back stacks of the John Hay Library. Christopher Geissler, the director of the library and its special collections, says manuscripts—for Dr. Mallon's novels, there can be as many as five drafts—make up the bulk of the archive, starting with Dr. Mallon's first major book, A Book of One's Own: People and Their Diaries, which was published in 1984.

The library's back stacks cover eight floors, plus an off-campus annex, and the collections of some authors fill as many as 50 boxes, depending on what's included and its completeness. Material can range from manuscripts to correspondence to writings from an author's youth—their juvenilia. In terms of manuscripts, Mr. Geissler says, the collection of Dr. Mallon—who got his undergraduate degree at Brown in 1973—is "remarkably complete," thanks in part perhaps to what Dr. Mallon described as his "archivist's temperament." He keeps everything.

Work on Dr. Mallon's collection began in 1991 when he and the library's former director, Sam Streit, started corresponding after Mr. Streit, a heavyweight in the field who's responsible for building much of the Brown library's author archives, showed interest in the writer from Long Island's Nassau County.

In Dr. Mallon's GW office, the storage space consists of a three-drawer filing cabinet and a few boxes, none of it overly secure. But the boxes, the cabinet, even the nooks of his desk, are chubby with ephemera. There are three-ring binders, manila folders, phonebook-fat stacks of paper—the stuff of Dr. Mallon's most recent drafts and research.

For one novel, Two Moons, he read a whole year (1877) of a defunct Washington, D.C., newspaper, The Washington Evening Star, printing relevant bits from microfilm to annotate and highlight. For Finale, he took a plane to Reykjavik one mid-October, just so he could be there the same time of year that Mr. Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev had their summit on nuclear disarmament in that big white house. Dr. Mallon went to the big white house, too, learning, among other things, that Mr. Gorbachev's security detail passed their time by watching Tom and Jerry cartoons in the basement.

Also in those boxes, cabinet drawers and desk nooks are his outlines. Human DNA has been mapped less precisely.

Dr. Mallon plans in "micro" and "macro" outlines. The micro versions are written by hand, chapter by chapter and sentence by sentence, in tiny letters, copied from a slaughtered forest's worth of to-be trashed pages. This outline is so final that it might as well be writ on diamond tablets handed down through sky-fire on Mount Sinai. The macro map, which he keeps in his computer, is more fluid. That's where Mr. Hitchens, not included in the early Finale plans and whom Dr. Mallon first met at a GQ party in Washington in the late '90s, snuck in. Dr. Mallon says he needed a Greek chorus character, someone like Alice Roosevelt Longworth in Watergate, who could do play-by-play and be funny about it.

The micro outline for the Landfall prologue alone is eight double-columned pages and gets as specific as "Bush waves." From the micro outline, Dr. Mallon handwrites a first draft—he says the micro outline is so detailed that this part is "almost rewriting"—which he then marks over with pencil before typing. Draft 2 is printed and marked in pen. So is Draft 3. Draft 4 is a full-on edit of a finished manuscript. It's the same procedure for a novel, for an essay, for a review, for anything he writes that isn't his morning diary entry.

"I still don't like writing," Dr. Mallon says.

There's always a Starbucks to-go cup on his desk. There's one there now. "I find writing difficult because there's still, with all that planning, even with all the outlining, there's still a certain fear of the blank page—that I'm not gonna be able to come up with that first draft.

"But I love rewriting because once I have something done, it may not be very good, but I can always make it better—I can make it measurably better. To me, the real stuff is in the revisions. ... If I can balance the self-loathing with a bit of self-flattery, I know what I'm doing when it comes to it."

IDEALLY, THOMAS MALLON says, he would write the way Rosemary Clooney sings—at least he'd write

in the style, of his interpretation, of the way Rosemary Clooney sings. To Dr. Mallon, Ms. Clooney is all intellect and vocal tautness, pared lean of aural fat to a mellifluous BMI. To his ear, she sings with a sureness of voice, of delivery, of elocution. She sings ex cathedra, and Dr. Mallon wants a drop of that lyrical infallibility.

Still, being a specific man, Dr. Mallon is specific about the Rosemary Clooney he wants to channel, and, for him, there are two incarnations. First, there is the Rosemary Clooney of White Christmas and of her first hit, "Come On-a My House," a jaunty song with a vaguely wicked feel and words that are both benign and suggestive at the same time.

This is not Thomas Mallon's "Rosie."

"Rosemary Clooney's probably my absolute favorite singer," Dr. Mallon says. "When she was young, she was this very pretty, perky pop singer who sang a lot of these novelty songs, a lot of junk, even. She wanted to be a much more serious singer—a jazz singer and a much more complicated practitioner of American standards. She really had two careers. She disappeared for a while, she had a lot of personal troubles and then she came back toward the end of her life and she made a whole huge series of albums with the Concord Jazz Quartet. They're fantastic."

That's his Rosie.

"She had such an intelligent delivery of lyrics," says Dr. Mallon, who wanted to do a magazine profile on Ms. Clooney, but nothing ever came of it. She died in 2002 at age 74. "She never gets in the way of the lyrics. She knows exactly how every word should fall. It's very simple and elegant."

While elegant, Dr. Mallon's style isn't succinct. There are clauses and parentheticals, reiterations and reestablishings. It's all well-crafted, but to Dr. Mallon, it's just not in Ms. Clooney's spirit of essential leanness. Her style, he says, has been elusive, and it's when he's listening to her—say, to the matured concision and clear consonants on 1983's aspirational "My Shining Hour"—that Dr. Mallon considers his limits and that maybe his strength is also his weakness: thoroughness and information.

"I think my writing has too many bells and whistles," he says. "Too many parentheses, too many flourishes—not so much stylistic flourishes, but there's too much stuff."

The line here is fine. The issue is balance and the ability to get out of one's own way and not muscle up on a strength. Ms. Clooney's singing serves, it seems, as the bumper on Dr. Mallon's authorial bowling alley, bouncing him back to the arrows when he slips to the gutter. He may not be Ms. Clooney's avatar, but she can at least be his compass.

Ariel Gonzalez, the professor and book critic, and Dan Frank, Dr. Mallon's editor of more than 20 years at Pantheon, agree that Dr. Mallon's novels can sometimes get snagged by too much planning, too much exposition. Mr. Gonzalez says that Dr. Mallon's characters can be too meticulous and jokes about his urge to "mess up their hair." Yet, the men say, it's a minor quibble—every writer must balance their strengths (Dr. Mallon often talks about the "tradeoffs" in writing)—because it's Dr. Mallon's attention to a thickness of "stuff" that cuts his niche in contemporary fiction.

A Spotify Playlist made by Thomas Mallon, inspired by Rosie.

Mr. Gonzalez met Dr. Mallon in 2001 at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference in Middlebury, Vt., where he did a workshop with Dr. Mallon that compelled him to read the author's work. Since, Mr. Gonzalez has interviewed him on WLRN-FM, Miami's NPR station, and positively reviewed several of Dr. Mallon's books for The Miami Herald, most recently Finale, praising Dr. Mallon's prose and his ability to cull heart from the gray space between history's facts.

The parts that Dr. Mallon seems to see as irreducibly complex in his writing, Mr. Gonzalez sees as welcome infrastructure, an effort to write good sentences and a dedication to incisive, cinematic scenes. Even Mr. Frank says that Dr. Mallon is a "clean edit," capable of great detail and wit.

Mr. Gonzalez wrote in his review of Finale, the Reagan-centered book, that Dr. Mallon is "truly incapable of writing a bad sentence" and that one of the novel's "many joys" is the "beauty and elegance" of the prose, which, in an interview this winter, Mr. Gonzalez described as "classically cool" and "refreshingly old-fashioned."

"I'd rather have his very well-detailed, formally structured novels than a lot of the rambling first-person monstrosities that we see today," Mr. Gonzalez says.

Dr. Mallon doesn't push boundaries or press hot buttons. He sticks to linear plots while avoiding the first person. It is, Mr. Gonzalez says, writing excised of "pyrotechnics."

"His writing style is extremely refined but not in an unapproachable way," Mr. Gonzalez says. "Anyone can read Tom's prose. ... It's very accessible in the sense that you can understand it if you want [and] every sentence really dazzles because of its crystalline nature. By that I mean his writing style is almost flawless. If you read his essays, if you read a page from his novels, you can see how meticulously crafted his prose is, and that also is very refreshing because sometimes there is too much sloppiness going on in today's fiction. He just doesn't jump on any bandwagons. He doesn't want to follow any bigger trend. He has a chosen path for himself and he's sticking to it."

Dr. Mallon, with a laugh, just calls it his "narrow talent." And while, to him, his writing may not be as trim as Rosie's singing, his fat is, at least, essential.

GORE VIDAL IN 1987 described history as the "agreed-upon facts," and, like Mr. Vidal, Thomas Mallon plays in the fissures between them, but carefully. Dr. Mallon sidles a threshold of plausibility, wielding his poetic license with tweezers, forceps and a large bottle of iodine. He's not offering alternate history, although he will commit the occasional fudging. His primary objective is to entertain and tell a good story, but he won't change a major agreed-upon fact, like the winner of an election, to do it.

His most egregious fudging in Finale is having Bette Davis get her Kennedy Center Honors in 1986 instead of 1987, just so she could play foil to Ronald Reagan, a former actor with whom she starred in Dark Victory in 1939.

It's a venial sin—especially compared to inventing an extramarital affair for Pat Nixon in Watergate—that still tweaks Dr. Mallon, who included Ms. Davis for her political affiliation (Democrat) and her entertainment value. He just asks that people not read his novels near the Internet.

Overwhelmingly, though, Dr. Mallon is offering what happened in addition to and not what happened instead of. He pokes around in history that's gone dark or never saw light, and he's proposing what might have been, even though that often means going inside a real person's mind. That, Dr. Mallon says, is the "huge license" he takes.

"Do I really know that Nancy Reagan and Ronald Reagan related to each other in the way that I have them doing?" he says. "It's not tampering with verifiable facts, like date and location, but it's a huge tampering with reality because it's an invention. I don't really know, but it's plausible."

Plausibility is the keystone of the conceit. In Landfall, like in Finale, in Watergate, in Dewey Defeats Truman, in Henry and Clara—all linked in a Mallonverse continuity—the historical figures will act as it seems to us they would, giving Dr. Mallon the cover he needs to stick in the odd fictional character, like the you'd-never-know-if-you-didn't-Google Anders Little in Finale. Thomas Mallon won't have George W. Bush slaying vampires. He practices fidelity to history and fidelity to the voices of history's figures.

A gifted mimic, Dr. Mallon eases conversationally in and out of impressions. At a lecture in February, Dr. Mallon went from Reagan to Donald Trump to Nixon to Merv Griffin and back to Reagan. To do Trump, he blusters hot air and bellows. For his Nixon, he hunches his shoulders and summons all the gruff and jowl he can. His Reagan sounds like James Mason dazed on nitrous oxide, which makes you realize that's actually kind of what Reagan sounded like. He's still working up his Bernie Sanders.

Before writing dialogue, Dr. Mallon speaks it out loud, muttering with what Dan Frank, Dr. Mallon's longtime editor, calls the author's "ventriloquist gift" and doing voices to himself in a dry run of plausibility. He's exploring what he describes as a "certain conscious empathy" that's part of making himself more completely the person he's writing.

Dr. Mallon wouldn't disagree that so far he's been most comfortable in Richard Nixon's head. He also knows when to inhabit a historical figure and when to cave to their inscrutability. Ronald Reagan was too opaque, so Dr. Mallon punted, as Mr. Vidal did on Abraham Lincoln. Dr. Mallon, as of January 2016, says he plans to go inside the head of W. for Landfall. But if he can't find Mr. Bush's voice somewhere in the blue ink of his Mont Blanc pen—a gift from astronaut Scott Carpenter after Dr. Mallon helped him with his memoirs—he can always find someone else's.

"He does wonders with Nancy Reagan, so that's sort of fantastic," Mr. Frank says. "He uses her to project

an understanding of Reagan, and for him to suggest that, even to Nancy, Ronald Reagan remained an enigma is sort of fabulous. It humanizes Nancy and at the same time it gives you an insight into just how enigmatic Reagan himself was."

Henry and Clara came out in 1994. Mr. Frank considers it the novel that made Dr. Mallon. In a September issue of The New Yorker that year, John Updike wrote about the novel—which follows the real-life couple seated next to Abraham Lincoln on the night of his assassination—and Dr. Mallon's work to that point, calling Dr. Mallon "one of the most interesting American novelists at work," in the penultimate sentence of an adoring review.

Henry and Clara also helped bring Dr. Mallon to Pantheon from Ticknor & Fields, uniting Dr. Mallon and Mr. Frank, who met over lunch, or a drink, maybe both— Mr. Frank doesn't remember exactly—in New York some time in the mid-1990s when Dr. Mallon was still working as the literary editor at GQ.

Dr. Mallon says his interest in historical fiction started with an elementary school reading of Men of Iron by Howard Pyle. He followed that with a novel by Elizabeth George Speare called Calico Captive, which is set during the French and Indian War. It's the first book that made him cry.

That was around the fifth grade, a year after he told his classmates from behind a "Vote Nixon" button that they had achieved previously unknown levels of wrong for supporting John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election. Dr. Mallon, then 9 years old and parroting his father's unconditional support of Richard Nixon, reasoned that Mr. Nixon was the correct choice to succeed President Eisenhower because he'd been vice president for eight years and Mr. Kennedy was just a lowly senator. It was an adroit argument, for a 9-year-old.

"It just seemed logical to me," Dr. Mallon says.

He can still name the members of Mr. Nixon's cabinet.

Five years later, at age 14, Dr. Mallon's interest in politics and historical fiction intersected for the first time, when he attempted his first novel, titled Impeachment. He made it through about a hundred pages—his "patient" father was the only other person to read them—before aborting and making his first go at keeping a diary. He would journal off and on until his first year of grad school—an anxious, unhappy, confused and overworked time in his life—when he took up the habit full time, writing a few hundred words every morning about the day before.

Dr. Mallon says he owes his writing career to his diaries, which may or may not end up in his collection at Brown—"I don't think I've had an interesting enough career for a biographer ever to be interested in it"—because, he says, diaries taught him the tightness of narrative that defines, and occasionally hampers, his novels.

Back in his office in January, Dr. Mallon's talking about Dawn Powell and the danger of "emptying your notebook." He's working on an essay about Ms. Powell, a little-known American writer whose acclaim came postmortem, for The New York Times Book Review. "Emptying your notebook" is when a writer uses every bit of research they have in an often vain attempt to show the reader just how much stuff they know. This, Dr. Mallon admits, is especially dangerous to him.

From there, he segues into how he balances planning and future inspiration, consulting a Powell anthology that seems sturdy enough to throw through the glass of a submarine porthole. He's looking for a Powell quote to explain all this and can't find the page. After a few seconds of futile searching, something occurs to him and he stops, shifting to the papers underneath the brick-shaped anthology.

"I bet I can find it on my outline."

A Novel Process

A Draft-By-Draft Look at Thomas Mallon's Latest Novel, Finale: A Novel of the Reagan Years.

Drafts Courtesy of the Brown University Library

"Through the open window Nancy heard five revs of the chain saw, his signature warm-up. Even before the tool could bite into the madrone's trunk, she knew that it had to be Ronnie --- not Barney Barnett, out there with him --- who was felling this particular dead tree. In no time at all he would clear three or four more from the property. Chopping them down remained his favorite form of exercise at the ranch."

Other Spring Features

Balancing the Books

Alumna Kyle Zimmer’s nonprofit, First Book, is pooling the buying power of educators and families in need to change the face of—and the access to—children’s publishing.

Tracking Terror in the U.S.

A new think tank finds the "democratization of terrorist recruitment" on social media is helping to create an increasingly diverse picture of Islamic-inspired extremism.