Poetry in Motion

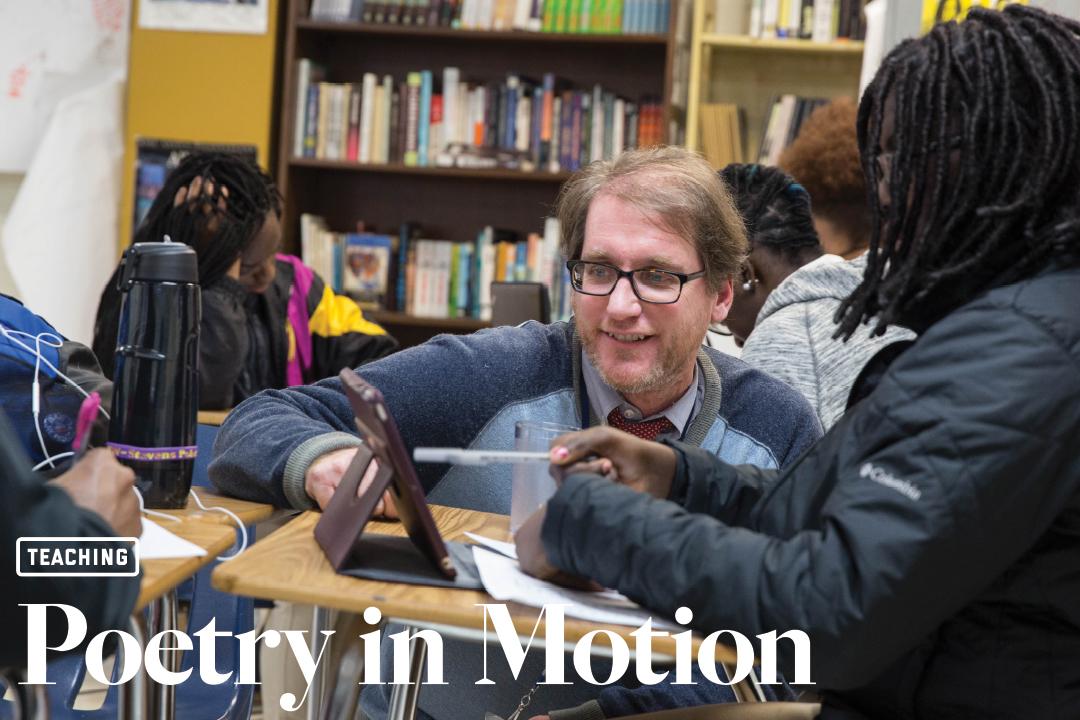

Topher Kandik, MEd ’07, works with an Advanced Placement English student at the SEED School of Washington, D.C. (Photo/Logan Werlinger)

A second-career English teacher helps kids find their voice

and confidence in school through "wrestling with words."

Topher Kandik was working as a high-level fundraiser at a prestigious arts organization when a chance encounter on a Metro train changed his life.

"This big guy came and stood over me. And, you know, when you're on the Metro and someone approaches you, you get a little nervous," Mr. Kandik remembers. "Then he said, 'Topher?'"

Mr. Kandik recognized the man as a former "chubby little boy" named Marcus. He had mentored Marcus in an after-school playwriting program in D.C.

"He was saying, 'I had so much fun doing that play. I need to get a copy.' It was the worst play ever—maybe eight lines—but the class had so much fun. And I thought, 'Why am I spending all day talking to rich people?'"

Before long, Mr. Kandik was a master's student at GW's Graduate School of Education and Human Development. After graduating in 2007, he joined the SEED School of Washington, D.C.—a public charter school for grades 6-12 in the city's historically underserved Southeast quadrant—and has remained there ever since as an English language arts teacher.

In December, he was named the 2016 District of Columbia Teacher of the Year. The award, given by the city's Office of the Superintendent of Education, marks the distance he has traveled from his shaky first day leading a high school classroom.

"I was a deer in the headlights,"Mr. Kandik remembers. "The students were taken aback. I had done all this planning, and I couldn't get a word out.

"But then someone cracked a joke and, in the long term, it was a net positive. After having that terror on the first day—you can't be afraid of making a mistake because you've already done it. The kids will forgive you, and you can move on."

FEBRUARY RAIN drizzled gloomily outside the windows of a conference room at SEED. Inside, two rows of teenagers stood facing each other, shifting and giggling. "Without conflict, there is no drama. Without drama, there is no poetry!" Regie Cabico calls out. "We are triggering some drama!"

Mr. Kandik leans forward a little, calmly narrowing the space between him and his students. "Remember," he says, "this isn't a shouting match."

Mr. Cabico—a D.C. performance artist Mr. Kandik had invited to help run a day of classes—backs him up, then readies the students again. "On your mark, get set, go!" In ragged unison, the group on the left says their assigned line: "I can't do it."

"It was the worst play ever- maybe eight lines- but the class had so much fun. And I thought, 'Why am I spending all day talking to rich people?'"

Like an orchestral conductor, Mr. Cabico raises his arms to cue the second row of students.

"You can do it!" they call back.

Their partners gain conviction—but, mindful of their teacher's directions, not too much volume. "I can't do it!"

"You can do it!"

Mr. Kandik, watching from the sidelines, smiles. Mr. Cabico was directing this 11th-grade English class in improvisational warmups as part of their preparation for the Poetry Out Loud competition.

When he first brought the nationwide competition to the school several years ago, Mr. Kandik says, it was almost impossible to convince his self-conscious teenage students to embrace it.

"They would just take a zero on the assignment," he says, rather than do something as potentially embarrassing as reciting poetry in front of their classmates.

But now, Poetry Out Loud is a SEED institution. Every student chooses a poem from the organization's database to memorize and recite, and classes choose one winner to send to a schoolwide contest in early March. Mr. Kandik says students are much more confident about participating and more supportive of their fellow competitors now that they've all had to do it themselves.

Last year's champion, a boy named Chris with a hesitant smile, was in the classroom. His winning selection: Joel Nelson's 28-line Equus Caballus. As Mr. Kandik explains that the winner at SEED goes on to regional and, if successful there, national competitions, Chris gestures toward himself with a thumb. That's gonna be me, he mouths jokingly. Chris, Mr. Kandik says later during an interview, is an example of the effect arts integration can have on students who may not excel in traditional academics.

"Every year, one or two students who have been failing up to then do well [at Poetry Out Loud], and then they take that success and build on it. Chris is an example," Mr. Kandik says. "He was pretty disengaged until Poetry Out Loud, and then, it was like it gave him an excuse to throw himself into something. Once he did that, it became his thing."

Mr. Kandik says one of his most essential insights as a teacher has been that no student wants to fail, but not all have the opportunity to envision themselves as successful.

"Even the most jaded, the most defiant kid wants to do well on stuff," he says. "They know they haven't, and they know it's been a chore, so they decide to throw their hands up. But that doesn't mean they're lost. That doesn't mean they don't want people, whether it's their teachers or peers, to tell them they've done a good job."

That realization is part of the reason Mr. Kandik tries to bring as many influences and activities into the classroom as possible. "The kid who hasn't been playing nice could make a switch and really be into something we're doing," he says. "You might not even know it in the moment, but eventually it comes out.

"That's like the Marcus realization," he says, referring to the former mentee in the playwriting class who stopped him on the Metro. "When we were actually doing [the class], it didn't seem like he cared. It was only later that I knew it had mattered to him." But Mr. Kandik is aware that in an educational environment that is increasingly focused on quantifiable results, it's not always easy to convince school administrators to diversify their students' opportunities.

"The sad thing is that [arts integration] actually helps with test results," he says. When students compete in Poetry Out Loud, for instance, "they're wrestling with words and interpretation, and, more importantly, they're becoming more confident and comfortable in the classroom."

INVITING OUTSIDERS like Mr. Cabico into the classroom has always been part of Mr. Kandik's classroom philosophy.

"He never views the classroom as a totally contained space," says Brian Casemore, an associate professor of curriculum and pedagogy who worked with Mr. Kandik during and after his time at GSEHD. "Those boundaries for him were porous from the beginning."

Mr. Kandik's previous career in arts fundraising left him with connections all over the city, and he works extensively with local and national organizations such as PEN/Faulkner, 826DC and the American Film Institute. "Part of what makes Topher such a good teacher is that he has his finger on the pulse of the city and its culture," says Mr. Cabico, who has known Mr. Kandik for almost a decade.

The day before Mr. Cabico's visit, Pushcart Prize-winning author Celeste Ng joined his Advanced Placement English class as part of a PEN/ Faulkner partnership. So did about a dozen students from Maret, a private school in Northwest Washington—an ongoing arrangement that Mr. Kandik says helps students from both schools broaden their horizons.

"I think there are artificial barriers we put up, and one of them is the school you go to," he says. "Why should kids at SEED not interact with kids from Wilson or Maret or Sidwell Friends?"

Making that connection is part of Mr. Kandik's commitment to educational and social justice. He wants his students, almost all of whom are African American and from low- to middle-income families, to have the same opportunities as their private school counterparts. He integrates current events like the Black Lives Matter movement into the curriculum, linking present-day activism with the long history of civil rights struggles.

"My AP class reads a lot of slave narratives, and we notice time and time again that knowledge is dangerous," Mr. Kandik says. "There are all these stereotypes of dangerous black youth, but in a sense that's what I want my students to be: dangerous, equipped with ideas. Once you have discipline and context, then you become a powerful person."

Other Spring Features

Class Assignment: Free a Man from Prison

As law students, Courtney Francik and Bart Sheard petitioned President Obama to commute a man's sentence—and he did.

The Ball is in his Court

Former GW tennis star David Haggerty recently took the helm of the sport's international governing body.