Just Passing Through (Winter 2016)

The Ship Hotel, built in the 1930s, sits in the snow along a bend on U.S. Route 30 in February 1971. The building burned down in October 2001. (Photo by Richard Longstreth)

With the automobile boom in the rearview and the Interstate Highway System ahead, a professor spent the late 1960s and '70s documenting a moment in time on the American road.

By Danny Freedman, BA '01

Tooling across U.S. 14 in South Dakota in a 1964 Buick Skylark, Richard Longstreth came upon three

gas pumps, stubby pillars of red, white and teal on a dirt landscape beneath a bunched-up blanket of clouds.

He took out his camera.

He did the same when he reached a snowy bend along U.S. 30 in Pennsylvania and saw the Ship Hotel, looking for all the world like a steamer moored to an Allegheny mountainside. Snap.

And at the fluid contours of Ralphs grocery in Beverly Hills, Calif., the charming stone faces of the Melinda Motel in Springfield, Mo., the starched angles of the Wake Up gas station in Indianapolis—snap, snap, snap.

It was the early 1970s, and Dr. Longstreth was attempting to capture a piece of the American road's loose and laissez-faire adolescence while some part of it remained. Half of the monolithic Interstate Highway System already had been built. The expanse—now nearly 47,000 speedy miles of pavement and knotted interchanges—would, ultimately, steal the pulse of the old U.S. Highway System, the scraggly network of arteries that had been spreading across the nation since the 1920s, trumpeting the era of the automobile.

Dr. Longstreth, an American studies professor who arrived at GW in 1983, spent more than a dozen years traveling those routes as life bounced him around the country, first as an undergraduate student in the late 1960s, then during a stint in the U.S. Navy, as doctoral student, a husband, a father and as the author of an architectural guide to Philadelphia.

Back and forth and back again, manifest destiny with a V-6 engine.

All told, he guesses he covered 60,000 miles.

"I was the voyeur," Dr. Longstreth says, looking back on the pursuit four decades later. "I was passing through and probably took, in many cases, the only photograph that's ever been taken of a lot of these [places]."

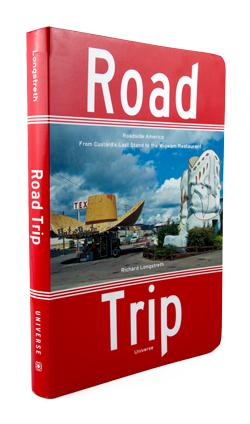

More than 200 of those photos have been collected in a new book, Road Trip. Many volumes have focused on the road's kitschier elements and its irrepressible goofball charm. Even this book's cover shows a gas station that sits under the brim of a colossal, 44-footwide cowboy hat and beside a proportional pair of boots (they housed the bathrooms). But in his new book, Dr. Longstreth democratizes the structures along the road, finding equal value in greasy-spoon hamburger stands, in past-their-prime motels and stately ones, in gas stations and the modern lines of a high-flying supermarket sign.

And he does it without nostalgia, opting instead for the practical disposition of a scientist: One landscape degrades and creates another, as it always has.

"In the mid-20th century, [highway commerce] was really a distinctly American thing," he says. "... None of this was really thought of as long-term. It was developed to capture a specific market at the moment, and investment was not such that it was going to last—or if it did, it would transform itself again and again and again."

"Like yea?"

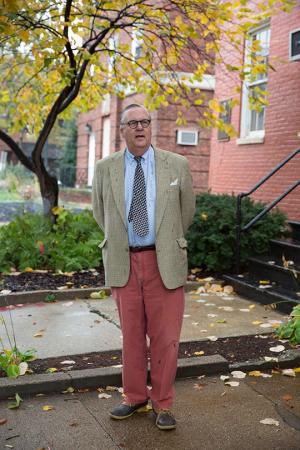

Dr. Longstreth is posing outside under an October drizzle. He's wearing a tie and houndstooth blazer with a handkerchief, taking directions from a photographer to look this way or that.

He is accommodating and jovial and speaks with a graceful polish—an unnamed colleague is "thus-and-such," the word "rather" comes out as the softer "rah-ther."

He didn't intend during his travels to produce this book. Instead, over time, the photos became

mainstays of Dr. Longstreth's lectures and informed his research. But a few years ago he felt one of those now-and-then waves of public interest in the American roadside and decided to hop on. The fact that the book exists and that he is the encyclopedic authority behind it would have been surprising at one point in his life.

"My father being an architect, I thought that would be the last thing I wanted to do," he says from behind his desk in a rowhouse on G Street, surrounded by the stuff of a life enamored of architecture and cityscapes. Across from the desk, five steel card-catalog-style file cabinets—and the shelf they create—are filled with slides, 180,000 or so, he figures. Behind him, a busted parking meter's red flag is sprung, blaring "Time Expired."

His father, Thaddeus Longstreth, worked first on the West Coast, then the East, with the influential architect Richard Neutra, before building a name for himself as a prominent modernist architect in Philadelphia and New Jersey.

Richard Longstreth, though, wasn't interested in the subject until he went to high school outside Newport, R.I., and encountered summer cottages from the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the time, he says, many were vacant or abandoned and could be wandered through freely. "It seemed like a lot of it was simply going to vanish."

He landed at the University of Pennsylvania as an undergrad in the mid-1960s and was surprised to find that it was, he says, the epicenter of the study of American architecture, and he took that on as his major. At that time, "if you were a serious art historian you did Renaissance or medieval, or something like that; became a classicist," he says. "And doing modern, especially U.S.? 'Welllll, if you can't hack the real stuff ...'

"Not everybody felt that way, but there was still something of a residue."

By the early '70s, Dr. Longstreth's interests had solidified around architectural history, and he enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of California, Berkeley, where "there were, for the first time, actual faculty members with whom you could discuss this sort of thing." Among them was foundational lecturer and essayist J.B. "Brinck" Jackson. But even he faced an uphill battle in higher education. "I confess," Mr. Jackson once wrote, "it was mortifying to realize that landscape studies, however important to me or acceptable to students, had no claim to academic legitimacy."

Dr. Longstreth funneled his research energy into early 20th-century architecture, particularly in San Francisco, though by then he also had a budding interest in so-called roadside vernacular architecture.

"If I said I wanted to look at the filling station or something like that, the most liberal of professors would have said, 'No, no, I don't think that would be very wise for you to do if you want to get gainful employment anywhere.'"

So he continued with it as more of a hobby, as he had since the late '60s. On short jaunts and long regional stretches, he drove the old highways with a Nikon F camera at the ready. There was no plan, other than getting from Point A to B. "You just go. You just go and see."

The 1970s brought a "generational shift" in the thinking, "a broadening of scope of what is worth investigating," he says. "You have the 'new history' of the early '70s. It's no longer just famous politicians and generals. It's looking at broader patterns and other things, and that was happening in architectural history, as well."

In the case of roadside architecture, Mr. Jackson and, later, Dr. Longstreth, believed that its very ubiquity in American life made it intrinsically worthy of study.

Dr. Longstreth's own underlying interest in these buildings was—and remains—hard to define, he says. "It wasn't the subject of any deep thought or anything of that nature. It was just things that I was looking at that seemed rather fascinating in their exuberance and, oftentimes, in their ad-hocism."

On the road, he says, "it's hard not to be interested if you're looking."

The U.S. Highway System, with its iconic numbered shields, was born in 1926. It effectively brought order to an agglomeration of existing roads and mapped out new ones, each built for the same reason that civilizations have been building roads for thousands of years: conquest—of people, of markets and, in more recent times, of curiosity and nature's magnificence.

Before and since, the story of the American road and the commerce that sprouted alongside it has had an almost meditative rhythm of growth, decline, cannibalism and, through it all, evolution.

Roads and businesses that prospered with the stagecoach suffered through train travel and the growth of cities, then bloomed again in the automobile age. In his seminal 1985 history, From Main Street to Miracle Mile, scholar Chester Liebs—who rode along with Dr. Longstreth on some of his trips—wrote that the neglect of rural roads spurred the 20th-century improvements that solidified the highways. Farmers needed to move goods. But there also was a blitz of new drivers. The ranks of registered cars rocketed from 8,000 in 1900 to more than 450,000 in 1910—and to 8 million in 1920, according to Dr. Liebs. And up and up it went, leading Dr. Liebs to call the view from the windshield "that most ubiquitous of twentiethcentury vantage points."

Along the way, roads consumed paths, and businesses moved into the shells of ancestors or built new storefronts, and revised, improvised and accessorized as needed.

Inside of three decades, though, parts of the U.S. Highway System were already feeling cramped and unsafe.

The Interstate Highway System, signed into law by Dwight Eisenhower in 1956, would change that—and a lot of other things.

The interstates brought the breathing room of 12-foot-wide lanes, 10-foot shoulders and limited points of access. Gone were the days of sudden stops for lefthand turns that sent speeding drivers darting to safety in the right lane. And gone were the days of needing to lumber along a two-lane highway going only "as fast as the slowest car," Dr. Longstreth recalls.

Historians consider the interstate system a marvel—"When in the history of the world has a public works program like that been undertaken?" Dr. Longstreth asks—even as they study what has been lost in all that was gained.

(And it's only here, when prodded, that Dr. Longstreth admits a bit of nostalgia. "As one of my professors said ... historians will write about Attila the Hun; it doesn't mean they're rooting for him.")

By the time Dr. Longstreth began documenting the road, the saturated Virginia stretch of U.S. 1 had been "obviated" by I-95, he says. The interstates would roll right over some of the old routes and bypass others. Interstate 5, for example, siphoned traffic from the highway on which the Hat n' Boots gas station sat in Seattle; it closed in 1988. Even that outlasted the archetypal Chicago-to-L.A. Route 66, which was decommissioned in 1985. In some cities, the interstates carved through neighborhoods and provided a pipeline to the suburbs that drained urban populations.

Driving the interstates, Dr. Longstreth found, "you don't really ... engage with the landscape around you,

you're separate from the communities that you are passing nearby," encountering only franchises "in little oases that are generally divorced from even the communities they're near to."

On the old two- and four-lane highways, he says, "you really get to see stuff. And not knowing what you're going to see, I think, is part of the fun of it."

Those structures all "have stories to tell about reception, about marketing, about the economy."

The architectural DNA of the highway shows how service stations morphed from places that fix horse-drawn buggies into ones that gas up cars. It shows the evolution of road food, from hamburger stands to diners built in the husks of old rail cars, drive-ins and, eventually, the making of a few fast-food kings of the road. And it shows how buildings represented a playbook for attracting eyeballs at breakneck speeds, which might explain why you'd have a statue of Paul Bunyan holding a hot dog or a gas station with a decommissioned bomber perched overhead.

It's like theater makeup, "which, if you see close up, is really frightening," he says. "But the audience is a distance away so it has to be exaggerated in order to be visible at all."

In photographing the buildings Dr. Longstreth says he wanted them to appear no prettier or messier than they are in everyday life. He wants the images to be up for interpretation.

Where there are people in the photos or some whimsy to the pieces—the California gas station attendant wearing a white apron or the two old cars with fins alone in a parking lot facing different directions, like steel codgers—the photos seem to capture a lived moment in time.

But photos of buildings can also carry an eerie idleness, an abandoned feel. Part of that, Dr. Longstreth points out, is practical: People and cars tend to get in the way of photographing a building. And, of course, "motels during the day are not places of hyperactivity," he says.

Elsewhere, though, the places are as still as they seem.

Flipping through the book, he points to a quiet, commercial strip in San Antonio that once thrived but was boarded up by the time he arrived. "That's urbanism," he says. Vacancies are "just part of the equation."

To be sentimental about it would almost be missing the point.

As his Berkeley professor J.B. Jackson wrote: "Ruins provide the incentive for restoration, and for a return to origins. There has to be ... an interim of death or rejection before there can be renewal and reform."

Which is to say: What Dr. Longstreth saw then, all that we see now, is not nearly the end of the road.

Other Winter Features

Jonquel's Best Shot

The Bahamian standout took a 900-mile leap and landed as one of the WNBA’s top prospects.

You Are Here

As president of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Daniel Weiss, BA ’79, finds his way anew on familiar turf.