Jonquel's Best Shot

(Illustration by Minhee Kim / Photo by Ned Dishman)

Bahamian standout Jonquel Jones took a 900-mile

leap and landed as one of the WNBA's top prospects.

By Matthew Stoss

All 6 feet 5 inches of Jonquel Jones—purveyor of hugs, GW's Bahamian women's basketball star and projected WNBA first-round draft pick—was folded into a chair. It was afternoon, late summer, and hot blue through the windows. A reporter asked what seemed like an intelligent question: Is there professional women's basketball in the Bahamas?

"In the Bahamas?" she says.

It wasn't an intelligent question. You could tell by all the laughter. She laughed with her body, all arms, legs and dreadlocks. She celebrates it when she laughs, the way people should but usually don't.

When the laugh passes, she explains why the Bahamas, while lovely, isn't the place to make a basketball career, and why, at age 14, she left her family and the option to wear shorts comfortably year-round to go 900 miles to suburban Maryland to live with people she didn't know and make new friends at a $10,000-a-year private school she couldn't afford.

"It was definitely a difficult decision to leave home and all that," Ms. Jones says. "But I'd been nagging my mummy for a very, very long time to come over. So I would always be telling her, 'I just want to play basketball. They take basketball seriously over there.'"

Somewhere between the fourth and seventh grades, Ms. Jones figured out that she had to leave the Bahamas to play big-time women's hoops—the kind that comes with cable airtime, endorsement deals and the squealing adulation of 9-year-old girls.

In Freeport, Ms. Jones' hometown of about 45,000 souls, there are three proper basketball gyms, one each at two high schools and a third at the local YMCA. There are outdoor courts, too, but in terms of the fancy developmental infrastructure that an aspiring young American hoopster might recognize—facilities, coaches, elite youth leagues—there's not much.

"If you don't come over here," Ms. Jones says of the United States, "it's really difficult to be seen and get the opportunity."

So, she came over. That was September 2008, when she was 5-9, more talented than skilled, a little terrified but confident enough. She got winter clothes, found a second family and made new friends with the help of the private school's small cafeteria.

Oh, and she got to play basketball.

Last season as a junior, Jonquel Jones averaged 15.3 points and 12.5 rebounds in 30 games for GW, stats that ranked sixth and first in the Atlantic 10. She was named the league's Player of the Year, as well as its Defensive Player of the Year, becoming just the fourth player to pull the two-fer since the defensive award was created in 1997.

As of late December, she was again averaging double-digit points and rebounds. Ms. Jones also broke the school record for rebounds-in-a-game when she grabbed 26 in a double-overtime win over the University of Iowa in November.

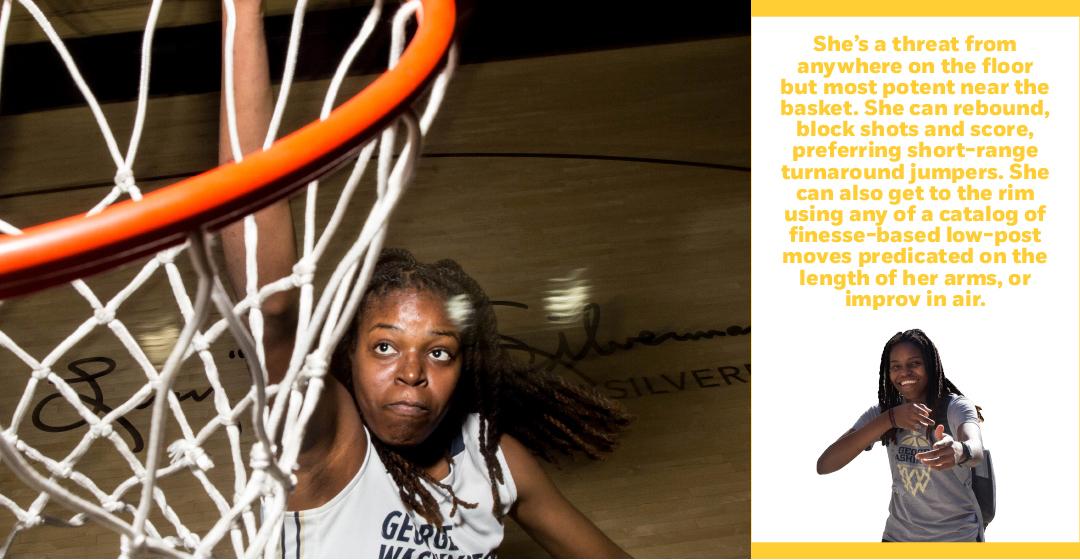

Although officially a power forward—she's got to be listed some way on the roster—she can play any position. She's a threat from anywhere on the floor but most potent near the basket. She can rebound, block shots and score, preferring shortrange turnaround jumpers. She can also get to the rim using any of a catalog of finesse-based low-post moves predicated on the length of her arms, or improv in air.

During an October morning preseason practice, she pulled off a shot that teased sky hook, turned scoop shot in the middle and finished as some genre of finger roll. Asked to repeat it a few weeks later, she had no idea what she did.

"An up-and-under?" she says.

No.

"A drop step?"

Kind of.

"Was it on a fast break?"

Maybe?

"What about this?"

Not that, either.

From the perimeter, Ms. Jones' jumper is controlled minimalism, repeated sweetly over and over, as if she's rotoscoping herself each time. Even if her shot hits the rim with all the grace of a large appliance, there's still a smoothness to how it left her fingertips. And it always feels like the next one's going in.

Her fade away?

"Legit," she says.

What about something ridiculous, like a 45-footer?

Ms. Jones' game is protean, and that is the crux of her pro appeal.

"She's ready to play at that level physically," says Doug Feinberg, who has covered women's basketball for The Associated Press for the past 10 years. "The other thing, she's not just purely a post player. I mean, [6-foot-5], 10 years ago, you would think, 'OK, that's somebody who goes in the post and they're a center and they do post-up moves—[but] she can hit the 15-footer. She can hit the mid-range jumper, which makes her more attractive. ... She can do some other things on the floor, which make her more valuable to WNBA coaches."

In the olden days of women's basketball, size largely defined position, with 6 feet being the approximate divider between guard and center or forward. In the last five to 10 years, position became less contingent on size. No longer are big players exiled to the low post and shamed for taking anything greater than a layup.

The shift occurred first in men's basketball, spurred by the influence of the European game, which emphasizes an all-around skill set for players of all sizes. It helped create an NBA in which LeBron James, at a very postsized 6-9, 250 pounds, can play point guard. The same evolution is now happening in the women's game, with players like Ms. Jones and WNBA superstars Candace Parker and Elena Delle Donne. These big players are able dribblers and outside shooters, unlike the centers and forwards of recent yore, who seemed clunked from a monolith factory—immovable objects with names like Patrick Ewing and Shaquille O'Neal.

"It's the progression of women's basketball," GW women's coach Jonathan Tsipis says.

The sport has grown a lot since the 1972 passage of Title IX, a law that, in part, assured equal funding for women's sports at the college level and effectively led to the creation of the WNBA in 1997, not to mention a proliferation of resources for girls at the youth level. Today, boys' and girls' hoops are as equal as they've ever been. Players are nourished in well-funded, nationwide, elite amateur leagues—a whole to-do centered on getting a college scholarship that's produced convention-bending players like Ms. Parker, Ms. Delle Donne and, now, Ms. Jones, who as a high school senior was one of the top players in the country. Collegiate Girls Basketball Report, a recruiting website that rates high school players, ranked her as the 38th-best player for the class of 2012, her senior year.

Dan Olson—who founded Collegiate Girls Basketball Report in 2006 and also directs ESPN's girls' basketball recruiting website, HoopGurlz—spends 50 weeks a year watching girls' basketball in gyms across the United States, seeing as many as 5,000 high school-age players. Years later, Ms. Jones still stands out.

"That's what everybody covets is a kid like her," Mr. Olson says. "I mean, she's [6-5], can handle the ball and she's wiry, long and lean, and she's a star in the collegiate scene. There's no doubt about that."

WNBA scouts have been regular guests at GW practice since Ms. Jones' sophomore year. In September 2015, Washington Mystics guard and ESPN women's basketball analyst Kara Lawson described Ms. Jones as one of the "more intriguing" prospects in the 2016 draft.

After the University of Connecticut's Breanna Stewart, the consensus no-duh best player in the draft who is projected to go No. 1 to the Seattle Storm, there isn't a lock to go No. 2. Maybe it's Ms. Stewart's teammate, Moriah Jefferson. Maybe it's the University of South Carolina's Tiffany Mitchell, the two-time Southeastern Conference Player of the Year. Maybe it's Jonquel Jones.

"It's obviously still early but her name is being mentioned," says Mr. Feinberg, the AP reporter. "Definitely in the first round, if not the first five picks."

Jonquel Jones wanted to go to America to play basketball. She begged her parents for years but they always said no. Money was a problem, as was Ms. Jones' young age and maturity. Her family also didn't know anyone in the United States, although overtures were made to a private school in Jacksonville, Fla.

The Joneses weren't against their daughter moving to the United States. It was an issue of logistics.

But in the spring before Ms. Jones' freshman year of high school, the Joneses got in touch with Diane Richardson through a family friend who had done exactly what Ms. Jones wanted to do: She went to the United States for high school and played Division I college basketball.

Ms. Richardson now is an assistant coach at GW, but at the time she was the head coach of the powerhouse, nationally ranked high school team at Riverdale Baptist School in Upper Marlboro, Md., its roster replete with elite players, many of whom got D-I scholarships, including Jurelle Nairn.

Ms. Nairn, nicknamed "Jello" by Ms. Richardson, lived with a host family while at Riverdale. She went on to play at North Carolina A&T, where she graduated in 2006. She's currently an assistant coach at Salisbury University in Maryland.

"We stayed in touch and all that," Ms. Richardson says. "And she said, 'Coach, there's a kid ... in the Bahamas that I think would benefit from being in the states, much in the same way I did.' I said, 'Well, Jello, tell me a little bit about her.' And she said, 'Nice kid and everything ... but needs to get away and have the experience of being in the states.'"

Ms. Richardson intervened. She got the Joneses on the phone and talked to an endearingly shy, "Yes, ma'am"-prone 14-year-old Jonquel and her parents, pitching herself, her family and Riverdale Baptist. It all sounded nice but the tuition cost too much. Plus, Riverdale isn't a boarding school. That meant Ms. Jones needed a host family. She didn't have one.

Nothing came of that phone call but Ms. Richardson kept in touch with Ms. Jones and her mother, Ettamae, building a rapport through that summer. Ms. Richardson also kept thinking.

"I had in the past taken kids under my wing, so to speak, because I came from a really difficult background and someone did that for me," Ms. Richardson says. "My husband and I talked about it, and I said, 'Why don't we sponsor her?' which was different than before, where kids would come and stay with me for a little bit and go home. This took a lot more."

Ms. Richardson grew up in the 1960s and '70s in Southeast D.C., on Benning Road, in a two-bedroom house she shared with her mother and her four siblings, her aunt and her aunt's five kids, as well as her grandparents. She says she wore her brothers' and cousins' hand-me-downs and that she'd get into fights at school when the other kids picked on her for dressing like a boy.

Eventually, Ms. Richardson, a superlative athlete—she says her brother used to race her against the boys and bet $2 she'd beat them (she never got a cut of the winnings)—went to Largo High School in suburban Maryland. There, a teacher named Norma Trax became more than a mentor. With Ms. Trax's support, Ms. Richardson went to Frostburg State University, where she played basketball and graduated in 1980, going on to found a lucrative investment firm, RCI Financial. She sold it in 1997.

Ms. Richardson credits Ms. Trax, with whom she remains close, for changing her life.

"I got to see where people have grass, picket fences," Ms. Richardson says. "She got me from being so rough around the edges, stopped me from being so defensive. ...And she stayed on me. Whenever I got unruly, she would take me to her house, and I got to grow up with her kids. She would take me places. She would take me to the fair. She would take me with her kids."

In September 2008, Ms. Richardson and her husband, Larry, invited Ms. Jones and her parents to visit. The trip started at BWI (with Ms. Jones going to basketball practice immediately after) and lasted about a week, becoming, in essence, an interview for the franchise rights to be Ms. Jones' American parents.

"I remember being terrified," Ms. Jones says. "... I met Coach Rich. I was walking up and she was full of energy and stuff, like this lady I hardly even knew is bumping me, saying, 'You ready? You gonna be strong in the paint?' and all this stuff like that."

Before the trip, there was an understanding that Ms. Jones may not go back to the Bahamas, even though she brought little more than a suitcase's worth of clothing, none of it cold-weather useful. The two families had made arrangements in case the meet-and-greet went well.

It did.

"It was like I knew Coach Rich," Ms. Jones' mother, Ettamae, says by phone from the Bahamas. "It was as if Jonquel was Coach Rich's daughter and I was helping to raise her until she got to that age and I was giving her back to her mother because there was no doubt in my mind that this was going to be the best place for Jonquel, the best family for her to be with."

Later, the Richardsons became Ms. Jones' legal guardians in the United States. She's on their insurance, in their wills and listed in Ms. Richardson's online bio as one of her four children. The Richardsons paid Ms. Jones' full tuition at Riverdale Baptist and the basketball court at their house in Ellicott City, Md., now has lights because Ms. Jones insisted on practicing even when normal people were sleeping.

"One of the things with Jonquel, the whole time she's been here, is she did not want to be sent back home," Ms. Richardson says. "She didn't want to fail and have to go back home."

But Ms. Jones had to get physically stronger. She had to refine her basketball skills to match an athleticism honed through a multi-sport childhood in which she excelled at soccer and track and field. That athleticism went mostly untouched by the gawkiness of a growth spurt that just won't die.

After a year in America, Ms. Jones was still raw, unburnished, more potential than payoff. She didn't make varsity full-time until her junior year and didn't start until her senior year, following a disheartening cameo as a sophomore.

That season, Riverdale played for a national championship in Erie, Pa., and after the bus ride back to Upper Marlboro, while in the car on the way home to Ellicott City, Ms. Jones asked Ms. Richardson a question.

"I had moved her up to varsity," Ms. Richardson says. "She was the only person who didn't play. I saw a tear afterwards and I was like, 'Oh, man,' you know? Of all the kids, my kid. ... And on the way home, she said, 'What do I need to learn to get better?'"

No one moment convinced Jonquel Jones that, to pursue basketball, she needed to leave the Bahamas. Instead, a series of events and realities coalesced inside her brain and over time pointed her in one direction.

As a kid, she watched the Junkanoo Jam, a Thanksgiving-time basketball tournament in Freeport, and she saw the skill gap between the American players, the Bahamian players and herself. Ms. Jones' mother says her daughter asked her at the time if she thought she'd ever be as good as those American players.

Then there was family friend Yolett McPhee-McCuin. Twelve years older than Ms. Jones, she went to the United States to play college basketball, becoming, it's believed, the first Bahamian woman to get a basketball scholarship without first playing in the United States.

It was also just the state of girls' basketball in the Bahamas. Outside of Ms. McPhee-McCuin's father—Gladstone "Moon" McPhee, who nearly 30 years ago founded a youth basketball program focused on coaching and skill development—there weren't opportunities for girls to play at a high level. Ms. Jones says her school season was 10 games, if that, and they played the same three or four teams. There's also nowhere to go after high school, and U.S. college coaches typically don't recruit the Bahamas.

Then Ms. Jones faced Americans for the first time. A squad from Boynton Beach, Fla., visited the Bahamas competitive basketball has been played.

"They busted our butts," Ms. Jones says. "This is back when I'm really young. ... and you think you're good, and then you're stepping on the court with these players and you're like, 'What the heck? She's the same age as me and she can do all this? And she's better than me.'"

The problem with girls' basketball in the Bahamas isn't talent, says Ms. McPhee-McCuin, the coach of both the Bahamian national and the Jacksonville University women's teams.

The athletes either play other sports—track and field is especially popular—or aren't cultivated as basketball players. It's a lack of emphasis, interest, infrastructure and resources. The talent, Ms. McPhee-McCuin says, is underdeveloped, the competition is weak and there aren't enough coaches.

A little girl, about 10 years old, on a neighboring island is doing a report for her P.E. class on the daughter of Preston and Ettamae Jones. The little girl's mom telephoned them to ask for anything—pictures, memorabilia, a brief oral history—that might help her daughter put together something A-worthy.

Fortunately for the little girl, the Jones family dining room is multipurpose. You can, of course, eat there—it has a glass table and four black leather chairs, for the easy service of chicken souse, chicken curry and Johnny bread—but the dining room's also good for archival research, especially if you're a little girl doing a report on your favorite Bahamian women's basketball player: Jonquel Jones.

The organization of that archive, however, Ettamae Jones admits, needs work. "I have to really try to organize it in a more fashionable way," she says, laughing.

Looking through the mementos of her daughter's basketball career usually turns a mess of baskets, envelopes and zip-shut plastic bags into a bigger mess of baskets, envelopes and zip-shut plastic bags. There used to be more but a hurricane destroyed the pre-high school stuff when they lived in Freeport. Not long ago, they moved to the Abacos, a Bahamian island group less than 100 miles west of Freeport.

In a more arranged future, there will be one authoritative scrapbook (but probably more) and perhaps color-coded, alphabetized files and the hiring of a professional who specializes in the conservation of memories. In short, there will be order. Glorious order.

The volume of material demands it, as does the fact that there will be more to archive. Ms. Jones still has the rest of her senior season, the Atlantic 10 tournament and, if all goes well, the NCAA tournament. The Colonials made it last year for the first time since 2008, securing the league's automatic bid by winning the A10 championship. GW last won the A10 title in 2003.

After that, for Ms. Jones, it's the WNBA draft. As of fall 2015, two thirds of the league's 12 teams had inquired about her, according to Mr. Tsipis, who is in his fourth season as the Colonials' coach. He guessed that by the time the draft gets here in April, every team will have scouted his star senior, who transferred from Clemson University eight games into her freshman year.

It's expected that Ms. Jones will be the first GW WNBA draft pick since 2009. That year, the Phoenix Mercury took Jessica Adair in the third round and 34th overall. None of the five GW players drafted have gone higher than 26th overall.

Folded in the chair and putting out a contemplative vibe, hands mostly still—she's not really a gesticulator—Ms. Jones considers this.

"I would say anybody in my situation, any player across the country that says they don't think about it—someone who wants to play basketball as their livelihood—they'd be lying. I definitely think about it a lot. Well, not a lot—but a good bit. But I try not to let it negatively influence me."

If it has or does, Ms. Jones doesn't show it. She walks around campus, laughing and hugging, long, tall and smiley. Mr. Tsipis says she might be the most recognizable athlete in Foggy Bottom.

"She's 6-5, and with her dreads, she's closer to 7 feet sometimes," he says. "... I think anybody that's been in a class with her, met her, that's what they always remember: this giant smile, this gangly kid who probably gave them a hug, and I think she leaves that lasting impression."

She has in the Bahamas. There among the 700 or so islands and islets, Ms. Jones is unconditionally adored. When GW played in the 2014 Junkanoo Jam, her presence alone filled the 500ish-seat gymnasium at St. George's High School with spectators.

Kids got out of class early to go, showing up en masse and in their school uniforms to watch her play. The adults came in homemade blue and white GW T-shirts featuring Ms. Jones' name and number. Later, Ms. Jones ended up on the back page, New York Post style, of The Freeport News, her picture ample above the fold and the crop agreeable to her fame. She was on the front page, too. Mr. Tsipis keeps a copy in his office.

And on the day the team arrived, when everyone else went to swim with dolphins, Ms. Jones went to meet Bahamian Prime Minister Perry Christie.

"She's a celebrity there," Mr. Tsipis says.

Jonquel Jones remembers crying after Riverdale Baptist lost that national championship game. That

was the game she didn't play because her coach and mother (American version) thought she wasn't ready, that there would have been "matchup problems." Ms. Jones, called up from JV, was the only player who didn't see the floor.

She cried for a lot of reasons. Riverdale lost. Her teammates were crying. She felt bad for the seniors who didn't win a title. She didn't play. She didn't help. The moment overcame her.

"I just didn't do anything to contribute to the team at all," Ms. Jones says. "It was tough because it was a situation where you leave your family, you leave everybody behind, and then you come into a place and the one thing you came over to do, you're not getting the chance to do."

Failure is hard, but this didn't qualify as failure. Action is a prerequisite for failure, and Ms. Jones was denied her action. That is worse than failing. At 16 years old, she—in her mind, at least—was a basketball star manqué.

"It wasn't even that I felt like she was being unfair as a coach," Ms. Jones says. "I knew I wasn't ready to play at that level and I wasn't proving it in practice."

That all seems dramatic, but none of the other kids traveled 900 miles just to play basketball and then not play. It was hard and it hurt, but even then she could cope like maybe other heart-crushed teenagers couldn't, because those kids (likely) didn't have Ms. Jones' unusually philosophical understanding of hugs.

In late October, Ms. Jones is at GW's media day. She's folded up again, this time at a table, in sniffing distance of the catered sandwiches, and talking to a reporter again. She's wearing her uniform (the home whites) and the interview's gone on for a while.

"Are we really having a 20-minute conversation about hugs?" she says.

Yes, but it's her fault.

"Whenever she meets somebody," Mr. Tsipis says, "whether it's the first time she's meeting them or somebody she's known for 10 years, she makes you feel like you're the most important person in the room. And usually, with her giant arms, she's going to hug you."

Mr. Tsipis' kids, ages 11 and 9, still talk about meeting her and getting arm-swaddled when she brings it in for the real thing.

"My son and daughter say it's like being hugged by an octopus," he says.

When Ms. Jones talks about hugs, you feel like you've been hugging wrong all your life—that you should call your mom immediately and ask forgiveness for all the years of shabby affection.

Ms. Jones, she has it worked out, speaking deeply and scientifically on hugs and their emotional value. The most important part, she says, is committing. Go in with all your might, assert your heart's dominance, and if it all comes up awkward, just leave with a smile.

"It's a like a free throw," Ms. Jones says. "If you go in like, 'Oh, I think I'm gonna miss it,' then you're more than likely going to miss it."

If someone comes at her with the handshake and she's feeling hug, Ms. Jones has devised a maneuver to function as a reverse into her octopus embrace. It starts with the handshake, but she pulls you in close for a chest-to-chest (the "dap") and finishes with a series of back pats.

"A hug is like, 'Oh, she really wants to get to know me,'" Ms. Jones says. "Or 'She really feels comfortable around me,' or, 'Dang, she just really made me feel comfortable.' So I think the hug definitely puts people in an area or a situation where they feel more like you're really invested in them, regardless of how you long they've known you."

It's philosophical for Ms. Jones. It's psychological.

The hug is the manifestation of whatever it was that made her—after an ego-rending benching—get up early the next morning and practice. Wherever those hugs come from, it's the same place that steeled a shy 14-year-old girl enough to leave her home and chase a basketball career 900 miles, to make new friends at a new school and to find a second family.

"In life, you have to be able to find moments where you just have to be able to uplift yourself, you know what I'm saying?" Ms. Jones says. "No matter what kind of situation you're in. If you can't do that, then who's going to be able to bring you up? If you can't love yourself, like they say, how are you going to expect someone else to love you? I think that's one of the big situations where people let their surroundings determine how they're going to be that day. Sometimes I'm a victim of it, too, because I'm a human being, but at the same time, you have to know when to be able to pull yourself out of that kind of mess and be able to just move on."

Other Winter Features

You Are Here

As president of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Daniel Weiss, BA ’79, finds his way anew on familiar turf.

Just Passing Through

With the automobile boom in the rearview and the Interstate Highway System ahead, a professor spent the late 1960s and '70s documenting a moment in time on the American road.