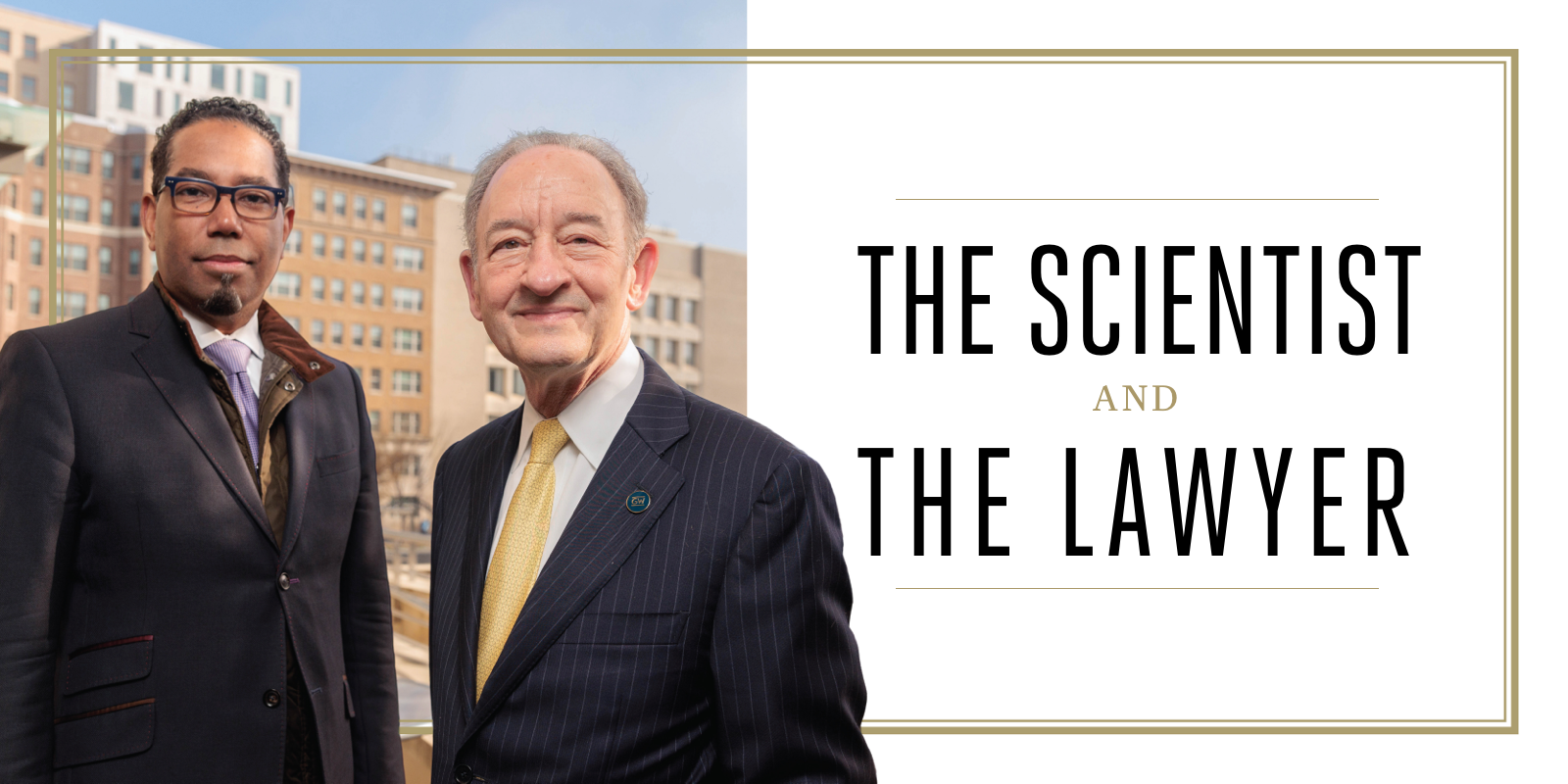

The Scientist and the Lawyer

From chemistry labs to courthouses to classrooms, GW President Mark S. Wrighton and Provost Christopher Alan Bracey have made a lasting impact at every step of their careers. Now they’re teaming up in new roles with a new mission—leading GW into its third century.

By John DiConsiglio

For a time in his life, George Washington University President Mark S. Wrighton felt most at home in a laboratory.

From his undergraduate days as a Florida State University chemistry student through his Ph.D. work at the California Institute of Technology to his tenure as head of the chemistry department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Wrighton could happily lose himself among vials and beakers. “By education, I’m a scientist,” he says, “and doing science is much more interesting than reading about it.”

Wrighton once imagined a contented career for himself in a lab coat and goggles. In the 1980s, his work in fields like solar energy and photosynthesis was cited in “Fortune,” “U.S. News & World Report” and “Esquire.” In 1984, “Science Digest” called him one of America’s brightest scientists. “I thought all along,” he says, “that being a scientist would be a rewarding and satisfying life.”

GW Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs Christopher Alan Bracey has had a lifelong love affair with the law.

As an editor of the “Law Review” at Harvard Law School and a clerk for a U.S District Court judge in Washington, D.C., Bracey fell under the spell of legal writs and reasoning. In the courtroom, he argued cases on telecommunication, antitrust and criminal law. He challenged segregation in the Baltimore public housing system. Burrowed deep in law library stacks, Bracey dissected precedents from Plessy v. Ferguson to the Dred Scott decision until he’d established himself as an author, lecturer and leading legal expert on race and the law.

Like a scientist, “lawyers think in terms of facts and evidence and looking for proofs,” Bracey said. “We use different skills and approaches, but we go after the same targets.”

Now the chemist who once considered dedicating his life to research and the legal scholar who can quote chapter and verse of constitutional law are stepping into key new roles at GW. As president and provost, Wrighton and Bracey are partnering atop the university leadership rung, taking the reins of an institution that weathered the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic and guiding it into the dawn of its third century.

The pair bring a wealth of experience to their new positions. Wrighton, 72, served as chancellor and chief executive officer of Washington University in St. Louis for nearly 24 years before being named as the next GW interim president in September. (He started his tenure Jan. 1 and is expected to serve for up to 18 months while the university embarks on a search for a permanent president.) He also spent five years as the provost at MIT. Bracey, 51, has held a number of leadership positions since joining the GW faculty in 2008, including vice provost for faculty affairs. At GW Law, he’s served as both interim dean and senior associate dean for academic affairs. Bracey was named GW’s permanent provost in February after serving as interim provost since June 2021.

In their short time as GW president and provost, they have faced a packed agenda of major university initiatives. Much of Wrighton’s early days in office were focused on leading the university’s pandemic response. He’s introduced himself to the community and immersed himself in campus life, attending basketball games and gymnastics meets, appearing at employee appreciation events for safety and facilities workers and visiting faculty, staff and students across schools.

Bracey and Wrighton walk through Kogan Plaza on an early spring day.

Bracey, meanwhile, has already launched task forces to address topics like diversity and inclusion and shared governance. Their multiple priorities also include strengthening GW’s interdisciplinary projects, enhancing research across all fields and overseeing the effort to expand the university’s financial aid resources and commitment to greater access to higher education. At the top of their list, they agree, is sustaining a foundation of world-class faculty and students—the cornerstone, they say, of GW’s academic reputation.

“We are here for the students and the faculty. We serve them,” Wrighton says. “Our objective must be to help our students and faculty realize their maximum potential with a minimum of difficulty. We have the responsibility to explore what we can do to make their future brighter.”

Indeed, while Wrighton and Bracey first made their marks in disparate settings—the lab and the law—both have firm roots in the classroom. They even continued teaching after taking on leadership responsibilities. Crediting his parents with fostering his passion for higher education despite never attending college themselves, Wrighton returned to teaching chemistry classes after completing his Washington University chancellorship. “I didn’t ‘step down’ from being chancellor, ” he says. “I ‘stepped up’ to a faculty position.”

Bracey was in Paris cheering on his wife in a marathon when then GW Provost Forrest Maltzman called him in 2016 and asked him to become a vice provost. Like Wrighton, Bracey had one request: He wanted to continue teaching.

“It was Paris in the springtime, I was in a good mood,” Bracey laughs. “I probably didn’t know what I was getting into.”

Wrighton and Bracey share other passions, including their pets. (Wrighton has a dog named Spike and a cat called Purrfessor; Bracey and his wife are longtime pug owners.) Still, the two believe their differences will also contribute to making them an effective team. Wrighton lauds Bracey’s institutional knowledge of the GW community. “I’m brand new, and [Chris] has history here and understands the culture and traditions,” he says. At the same time, Bracey praises the new president’s fresh vision and extensive leadership track record. “Mark’s arrival signals an important transition in the trajectory of the university. His energy and experience bring something new that we really needed. It is a very exciting time to be part of the administration.”

In a conversation with “GW Magazine,” the leadership duo talk about the rewards of their new roles, the resilience of the GW community and how a scientist and a lawyer can partner to lead a university.

Wrighton addresses alumni and friends at the GW + You Opens Doors New York City reception, held March 28 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Credit: Ben Solomon

GW Magazine: You’re both stepping into new leadership positions after successful careers in other roles. Why take on these new challenges now?

Wrighton: I wasn’t looking for a university presidency when I wrapped up my chancellorship at Washington University in 2019. I was happy to assume a full-time faculty position. But then, in the spring of 2020, the world went into lockdown, and my wife and I suddenly found ourselves homebound. I spent more time with my wife in six months than we had in the preceding 20 years. And we discovered—happily—that we were each other’s best friend.

But I started thinking there must be something beyond walking my dog and catching up on television for the first time in my life. I felt energetic and refreshed. I was receptive to taking on something meaningful. Of course, GW has a high reputation—mostly because of its students, its faculty, alumni and staff. Coming to GW held out the opportunity to work with outstanding academic leaders and talented individuals like Chris. And the capstone was that we have a daughter [a GW School of Business alumna] and grandchildren in the area who we hadn’t seen very much in the last few years.

Bracey: One of the things I’ve learned about being in the provost office—and this is true of other offices as well—is that we are in the people business. University leadership at any level is all about connecting with and helping others. It’s become a passion of mine to take on the challenges of enabling our community—deans, program directors, department chairs, faculty—to aspire to excellence and succeed in all areas of their life cycle. And I’ve found I enjoy basking in the reflected glow of others. With Mark’s arrival, I’m lucky to be in a position where I can watch him, learn from him and witness the highest levels of leadership in very close proximity.

GW Magazine: Chris, you’re learning from Mark’s experience. You’ve been a fixture at GW for nearly 15 years. What can you teach him about this community?

Bracey: Mark’s been meeting folks here on campus—faculty, students, staff. So he’s already getting a sense of what makes our community distinctive.

One thing that I would want to share with him is that our community members really care about each other—about the people and the institution. The bonds they’ve forged in their schools and departments are enduring and robust. The faculty care about the staff and their well-being; the staff care about the students; the students are interested in knowing how the faculty and the administrators are doing.

The folks who work for GW would do anything for it. And that’s what I think allows us to pull together in tough times—like our pandemic response. As a result of the faculty pulling together with the staff, we were able to migrate much of our coursework online in a week’s time. And the students were accommodating. They understood that these were challenging circumstances that would require everybody to work collectively.

GW Magazine: Speaking of the pandemic, this community has been through a lot. What message do you have for them after a wearying few years?

Wrighton: The pandemic has been a huge challenge, of course. I’m grateful that Chris and many others here created a great infrastructure to deal with the pandemic problems. But I understand how hard it’s been. For some, it’s been the most difficult years of their lives. Younger people have been disappointed with respect to dashed dreams. Many people have changed their outlook on the future.

I would say I admire people who have shown resilience and a sense of optimism. There is much to be optimistic about.

An academic institution provides a great setting to learn from the past and respond to the challenges of the present. What I’ve seen here at GW are people who are ready to focus on what we learned through the course of the pandemic and eager to press on, to strengthen the institution. I sensed that when I watched the double Commencement ceremony in October. I saw the evidence of pride and enthusiasm when you celebrated 200 years of existence as an academic institution. I also have experienced firsthand the excitement of our community of alumni, families, donors and friends, and the commitment they demonstrate to our university—whether they are in California, London or New York City.

Moving forward, we all have the responsibility to take what we’ve learned in these challenging times and make this an inflection period. To me, there’s no question about whether GW will survive. The question is, are we going to thrive in the future? I think we are already seeing that.

GW Magazine: Can both of you talk about your priorities? How do you envision GW’s direction under your leadership team?

Wrighton: I like to refer to a pair of words—distinguished and distinguishable. We must be both.

We’re not striving to be a Xerox copy of any other academic institution. We can develop programs of real significance that contribute to society; we can strengthen the student experience, expand research opportunities, encourage interdisciplinary work. And we can do that by building on the strengths that we already have—the many distinguished and distinguishable aspects that make GW unique.

The Elliott School of International Affairs, for example, is not an academic area that many other institutions have. It is one of the most outstanding programs in the country, and it is right down the street from the Capitol and the White House and the State Department, where policies relating to international affairs are formulated and adopted.

Another example is the great Milken Institute School of Public Health. It is providing guidance, education and scholarly work that is extremely important in these times. The era ahead is very promising for such a school. Every school across the institution can be on a path to becoming stronger and higher in impact.

Bracey: I would just add that the foundation for everything that the president is talking about is students and faculty. That means our aspiration has to be recruiting the most qualified set of students—really smart people who are genuinely curious about exploring the world of ideas. At the same time, we want to recruit the world-class faculty that will produce and disseminate research that can transform the world.

Mark talked about making an impact. That’s why people come to GW—they want to be impactful. Students come to GW because they want to have an impact on the world. And you can see the impact they have by looking to the long list of accomplishments of our distinguished alumni. Our faculty come to GW because they want to be impactful instructors and researchers. People don’t come to GW to be passengers. They come here because they want to drive.

Photography: William Atkins