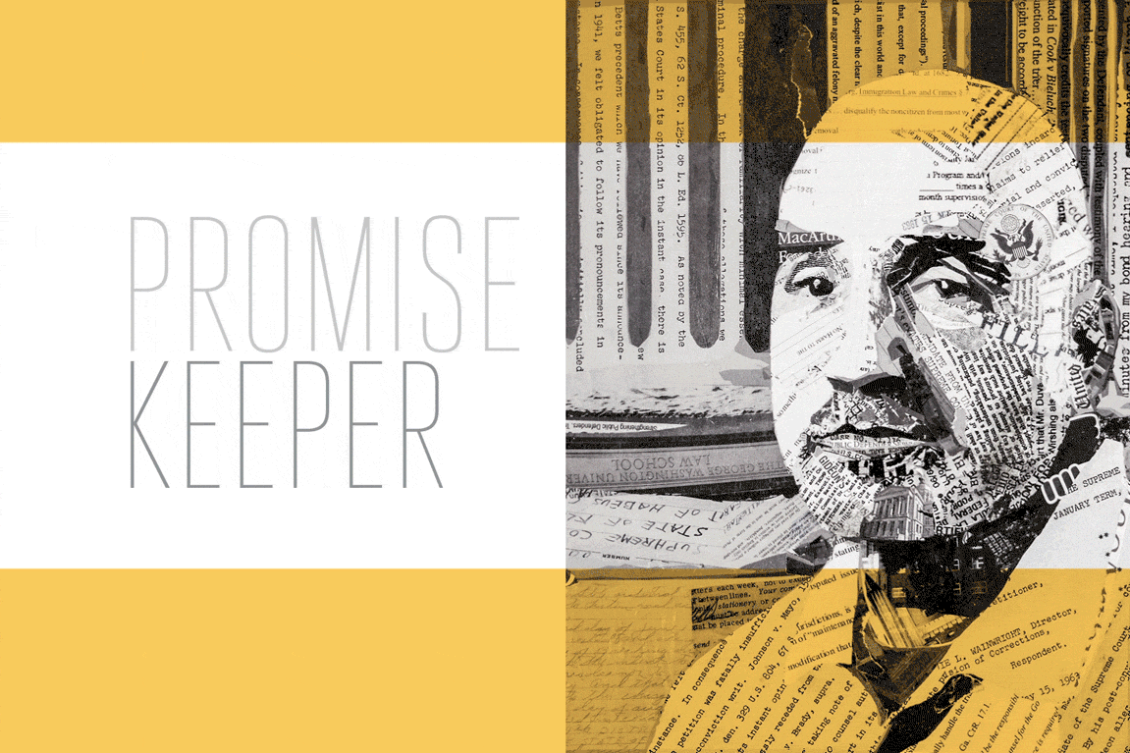

Promise Keeper

(Illustration: Minhee Kim. Reference photo: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

MacArthur Fellow Jonathan Rapping, JD '95, is helping the government fulfill its duty to stand up for the indigent accused with his program, Gideon's Promise.

By Tony Rehagen

Anna Kurien wasn’t sure she could keep doing this job. She had joined the Fulton County Public Defender’s Office fresh out of law school in 2008 and dedicated four years to representing the indigent in Atlanta. But this was her first murder trial— and she had lost. She had no idea how she was going to go back into that courtroom. For two days, she couldn’t even get out of bed.

Ms. Kurien felt that her client’s case was clearly self-defense. She spent months not only piecing together events, but getting to know the accused and his family, gradually painting the portrait of a hardworking man who was trying to protect himself. But he was an undocumented immigrant, a Latino, and it seemed like that was all the jury, the prosecutor, even the judge could see.

“They didn’t care about him,” Ms. Kurien says of the 2012 case. “They didn’t think of him as human.”

Now he faced a mandatory sentence of life in prison, while Ms. Kurien faced the task of making his wife and child understand that they would never see their husband and father out from behind bars again. The stepson had given Ms. Kurien a letter, written in the broad, crooked pencil strokes of a 7-year-old, to read to the judge at the sentencing. Please bring my Daddy home. I miss my Daddy.

It would have been easy to just quit, to walk away and apply her education to a less daunting aspect of the law. It might have been easier still to fold up that child’s letter and stuff it deep down in her briefcase, to give in to the exasperation felt by overworked, under-resourced and unappreciated public defenders across the nation, and to stop living and dying with each case. “I didn’t think I had the strength to face that loss again,” she says.

She found fortitude in the teachings of Jonathan Rapping. Ms. Kurien had first met Mr. Rapping, or “Rap” as he likes to be called, in 2006, when she was an intern at a neighboring public defender’s office and he was a trainer for the Georgia Public Defender Standards Council.

More than just teaching courtroom procedure and caseload management, Mr. Rapping had emphasized the public defender’s role in standing up for the humanity in their clients, who are often in the worst trouble of their lives with no one else to turn to. As a society, we have throw-away people, she remembers him saying. If you want true justice, you must remind the system that these are human beings.

“Rap was like a small, bald, Jewish Jesus,” Ms. Kurien says. “He was dedicated to the church of public defense.”

The following year, Mr. Rapping started what would become Gideon’s Promise, an organization devoted to that ideal, work that would eventually win him a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called genius grant. In 2010, Ms. Kurien was enrolled in the Gideon’s Promise training program when Mr. Rapping pulled her aside and told her she was “born for this.”

“I clung to those words,” she says. She also held on to something else Mr. Rapping had preached: “The only way to accurately convey a person’s humanity is to open yourself to their pain.”

From the 24th floor of a nondescript high-rise, the offices of Gideon’s Promise look out over downtown Atlanta. The broad windows and their majestic view belie a workspace that is becoming more and more cramped to contain a budding staff. The baseboards of Mr. Rapping’s modest office—he yielded the most spacious quarters to the executive director, who also happens to be his wife—are lined with framed news clippings, three-deep in some places; trophies that can’t find room on the wall. Most of the clippings are brand new, fruit of the recent MacArthur grant. “We are growing,” says the 48-year-old Mr. Rapping. “All of a sudden people are paying attention.”

Mr. Rapping first became aware of Gideon v. Wainwright—the landmark 1963 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states must provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who cannot afford it—when he was a student at GW Law School in the mid-1990s. But at the time, it was just another chapter of a case law book.

“In law school, you learn laws in theory,” he says. “But you can’t understand how they are applied or the impact they have on people until you have a real-world setting.”

He got that during his first summer, through an internship with the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia. Mr. Rapping’s mother had been politically active in the 1970s, and he had grown up around attorneys who defended protesters. In his young mind, defense lawyers were superheroes who stood up against the powers of the state. He says that the lawyers he met at the D.C. public defender service lived up to that archetype.

“They were passionate and hardworking,” Mr. Rapping says. “They spent their days defending the world.”

He shadowed them for the next two years and saw how their work affected individuals, families and entire communities by helping people when their need was most dire.

He had heard the call.

“In the classroom we learned about the concept of justice,” he says. “Most lawyers never think about it again. I didn’t want to be one of those lawyers who realize that, as someone once said, ‘the first thing I lost in law school was the reason that I came.’”

During his third year at GW Law, Mr. Rapping took part in the school’s criminal defense clinic. There, he represented his own clients, and following the example of his mentors, he got to know them beyond their legal predicaments. He built relationships, and he saw that they all had similar stories: They were from poorer parts of D.C., had come through schools that didn’t work, faced some sort of mental health challenge and had social needs that weren’t being met.

“These are people we walk past on the street,” he says. “But we’re completely desensitized to their struggles. In many ways we ignore them.” He was not going to ignore them anymore.

Upon graduating in 1995, he joined the public defender service as a staff attorney. The office—a federally funded, independent legal organization—stood out to many as a model, even as the city itself was struggling to shed its “murder capital” moniker. Mr. Rapping specialized in cases involving domestic abuse and sex offenses. He went on to become training director, reminding new attorneys that law was more than a code of rules and procedures.

In 2004, after nine years with the D.C. office, he received an offer to go to Georgia to set up a new statewide training program for public defenders. It was an opportunity to impart the ideals he had formed in the District to a state’s worth of young attorneys. But when he arrived in the South, he soon realized that the supportive atmosphere and enthusiasm for public defense that he had taken for granted in D.C. was more the exception than the rule.

Ilham Askia had her own preconceived notions about public defenders.

When she was 5, her father was arrested for an armed robbery he had committed years prior. Since then he had straightened out his life, met and married Ms. Askia’s mother, converted to Islam, had three children with another on the way and opened a small fish market in Buffalo, N.Y. But the attorney appointed to represent him didn’t seem interested in telling that story, showing the jury and the judge that he had changed. Ms. Askia’s father was quickly convicted and sentenced to 10 years in Attica.

It broke the family apart. Her parents separated, and even after her father was released, he was never the same. Detached and unaffectionate, he lived alone in his mother’s cinder-block basement until he violated probation and went back to jail. Ms. Askia’s brother ran afoul of the law and wound up in prison himself. She doesn’t blame the attorney for her father’s actions, nor those of her brother. But she knows how far and deep the cracks of one criminal case can run and the feeling of helplessness when the one person who was supposed to defend you fails to stand up.

So she was skeptical of Mr. Rapping when she first met him during a teaching externship in D.C. Outside of school, she was a server at a bar that Mr. Rapping and his colleagues frequented after work, and as the schoolteacher gradually got to know the young public defenders, she saw they were different—Mr. Rapping, especially.

After the two started dating, she noticed that he would talk about his clients like they were extended family members. He would drive to the jail and arrive as soon as the gates opened to meet with a defendant. He secured housing for some, clothing for others, day care for parents who couldn’t bring their children to court. “He went far beyond the scope of what I thought was expected of a public defender,” Ms. Askia says. “I wish somebody had done that for my dad.”

Once she and Mr. Rapping were married, Ms. Askia became an informal part of that support network. She followed him south in 2004, when he accepted the offer to set up the training program in Georgia—where he would need her encouragement more than ever. “I learned about Gideon v. Wainwright in law school,” says Mr. Rapping. “But I didn’t appreciate it until I moved to the South.”

The fledgling attorneys he encountered in Georgia were as smart, skilled and well intentioned as any he had worked with in Washington. But the system was broken.

Each state and even some individual counties have their own public defense systems, forming a patchwork of structures built from different blueprints and parts. Legislatures at the time were slashing budgets all over the country, leaving public defenders offices underpaid and understaffed. And while national standards established by the American Bar Association and a presidential commission recommended 150 felony cases per attorney each year, some public defenders in Georgia were facing upwards of 400—and as many as 900—cases total.

In the courtroom, Mr. Rapping says, it could feel at times like prosecutors and even judges were more focused on expediency than justice, and that public defenders were pressured not to gum up the works by rejecting plea deals and going to trial. Over a four-year period, one Georgia attorney saw 99 percent of his 1,500 cases result in a plea.

“I started to see systems that had come to accept the poor representation of poor people,” Mr. Rapping says. “Young public defenders were talented and passionate, but the system was beating the passion out of them.”

When Mr. Rapping was called on to help reform the New Orleans public defender’s office in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, he saw the problem extended beyond Georgia. He returned to Atlanta in March 2007 and secured a grant from the Soros Foundation to start his own organization, dedicated to giving young public defenders the tools they need.

Ms. Askia quit teaching to join him as executive director, overseeing fundraising and staffing for the newly dubbed Southern Public Defender Training Center, later renamed Gideon’s Promise.

The name wasn’t scrapped merely because it was a mouthful.

First, even though it was important to instruct young attorneys in verbal and procedural tactics, like challenging a confession, and on building graphics and multimedia into defense strategy, Mr. Rapping’s organization was much more than a training center.

As much as technical support, these young attorneys and many more-experienced public defenders needed moral support in the struggle against the status quo, and Mr. Rapping’s expanding roster of disciples provided that.

“Today you can send out an email asking for help,” says Ms. Kurien, the Fulton County lawyer, “and within 30 minutes you have eight lawyers offering advice and even their phone numbers.”

In fact, Mr. Rapping’s movement was growing so rapidly that it could no longer be contained by the name “Southern.” Gideon’s Promise was battling a nationwide problem.

In 2013, at an event marking the 50th anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright, then-Attorney General Eric Holder noted that, across the country, public defense systems “exist in a state of crisis,” which he called “unacceptable and unworthy of a legal system that stands as an example for all the world.”

For Gideon’s Promise, what had started as a three-year training program—a two-week “boot camp” and semiannual meetings—for 16 attorneys in two offices in Georgia and Louisiana had soon grown to include 300-plus lawyers in more than 40 offices across 15 states. The curriculum, primarily geared toward new public defenders who either apply on their own or are sent by their offices, also evolved into five programs aimed at different audiences, from leaders of public defender offices to students still in law school. Last year, Mr. Rapping struck a deal with the state of Maryland to apply the Gideon’s Promise model to the entire statewide defender system.

Then last September, he was notified that he was one of 21 MacArthur Fellows—recipients of the coveted $625,000 no-strings-attached grants from the MacArthur Foundation. The sudden windfall of cash, which comes in quarterly payments, certainly has been appreciated. And under the aura of the fellowship’s spotlight, Gideon’s Promise picked up 170 new donors in the six months that followed.

Mr. Rapping and company are now moving to a bigger Atlanta office to accommodate a growing staff, and Ms. Askia says the five-year plan is to have a freestanding training center that would host entire staffs from other states.

But for Mr. Rapping and Ms. Askia, the most basic aspects of the MacArthur grant far exceed coins in their coffers: The recognition validated their work and sacrifice. And with every interview they grant to newspapers, magazines and TV stations, their message is carried to new audiences—not just beleaguered public defenders who might be on the verge of giving up but also members of the general public, taxpayers who may not understand or even acknowledge the problem until they or a loved one find themselves in trouble with nowhere else to turn.

“Gideon’s Promise is about a cultural transformation,” Mr. Rapping says. “Without that transformation, all the money in the world won’t get us to equal justice.”

Change is slow, even on an individual basis. Mr. Rapping teaches young attorneys that they can’t flip a switch and throw themselves into every single case. Even in an ideal setting, public defender offices carry a heavy caseload, he says, and the goal should be to make more of a difference each year. This year it’s 20 cases, next year try for 30. And 40 the next. Along the way, he says, “you have to forgive yourself for those who slip through the cracks.”

With Mr. Rapping’s support, Ms. Kurien—the Georgia lawyer and protégé—was able to move on from that first murder case and return to the courtroom. This year will mark her eighth with the Fulton County Public Office, an anniversary she says she would not have seen if not for Mr. Rapping, Ms. Askia, and Gideon’s Promise.

Last year, Ms. Kurien attended a Gideon’s workshop on how to make a biographical video for clients, aiming to help the court see the person behind the defendant’s table. She chose a case that she felt had potential for mitigation. Then she filmed interviews with the client’s fiancé, her 15-year-old daughter, her work supervisor and a childhood friend. She took photos of the 15-year-old’s room, the walls papered with letters the client had written her daughter from prison. Ms. Kurien then edited down hours of footage to a five-minute video and showed it to the district attorney.

Her client, who was facing a mandatory 25 years in prison without parole, had her sentence reduced to three years.

Ms. Kurien has more than a few personal success stories she can attribute to Gideon’s Promise. But perhaps more important are the lessons she is now able to pass on to her younger colleagues. “When I see young attorneys with desperation on their faces,” she says, “I see myself in them.”

Other Summer Features

Five Years Later in Haiti

Half a decade after a catastrophic earthquake, a Pulizter Prize winner finds that life in the beleaguered nation goes on, as it always has.

Reuniting Babies and Their Bottles

Feeding tubes and surgeries offer an imperfect fix for infants with disorders that leave them unable to eat. The problem is in the brain, and that's where GW researchers are looking for a cure.

"We Are Always Activists First"

Students on the front lines of a national movement against sexual violence find a battlefield with no boundaries.