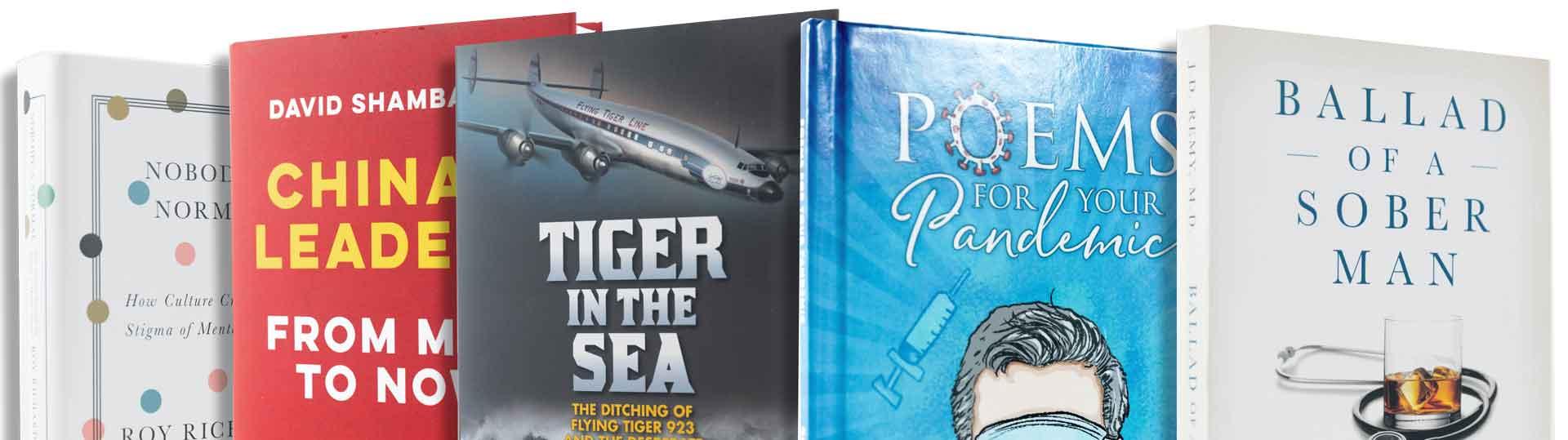

Bookshelves

Bookshelves

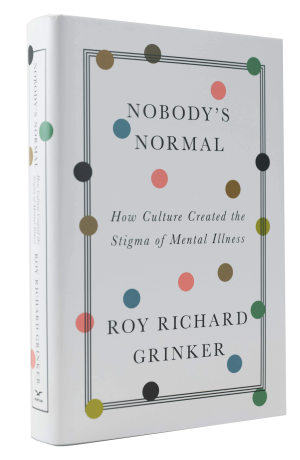

The Illusion of ‘Normal’

In Nobody’s Normal, Roy Richard Grinker draws on his personal history—from his daughter’s autism to his grandfather’s analysis with Sigmund Freud—to challenge mental illness stigma.

In his undergraduate anthropology class, Roy Richard Grinker, professor of anthropology and international affairs, often cites statistics to help his students grasp the worldwide prevalence of mental health disorders.

More than 260 million people suffer from depression, he tells them. Approximately 1 in 50 children in the United States are diagnosed with autism each year. And, at any particular time, 25 percent of Americans meet the scientific criteria for a mental illness—not to mention the tens of millions more who regularly suffer through waves of anxiety and sadness.

Nobody’s Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness (W. W. Norton & Company, 2021) By Roy Richard Grinker, professor of anthropology and international affairs

As Grinker checked off figure after figure in a recent class, one student observed, “So, nobody’s normal.”

Not only had the student summarized the point of Grinker’s lecture—in mental health, differences aren’t always deficits—but she’d also given him the title of his next book. In Nobody's Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness, Grinker reveals how centuries of moral judgments have fueled stigma against people with mental illnesses.

Few scholars are better qualified to cast a discerning eye on the history of mental illness than Grinker. He was raised among three generations of eminent psychiatrists. His grandfather was one of Sigmund Freud’s last patients. And his books often draw on his personal history—including his daughter’s autism diagnosis, his travels among hunter-gatherers in central Africa and his conversations with his students—for illustrations of shifting cultural perceptions.

In his book, Grinker acknowledges the challenges people with psychological conditions face, but he sees a light at the end of the tunnel. As old mental health prejudices are rejected and differences embraced, Grinker believes his student was right. “Normal is an illusion,” he said—and one that’s fading fast.

“We learned from our culture to put stigma and mental illness together,” he said. “And that means we can also learn to take it apart.”

Embracing Differences

Growing up the son of a psychiatrist in Chicago—and with his psychiatrist grandfather living across the street—Grinker said his family believed that everyone had a touch of mental illness. His grandfather (also named Roy Richard Grinker) regaled him with stories of working with Freud, from the legendary analyst’s stale-smelling Vienna waiting room to his wish that some psychiatric conditions would someday be no less stigmatized than the common cold. During World War II, Grinker’s grandfather conducted pioneering studies of American pilots suffering combat-related distress. “He said his patients were not abnormal, they were normal people in abnormal circumstances,” he recalled.

Grinker’s family was disappointed that he didn’t pursue psychiatry. (His wife is a psychiatrist with the National Institute of Mental Health.) But as an anthropologist, he has become a leading voice in framing an understanding of cultural attitudes toward mental health. In his book, he traces the origins of mental illness stigma to the Industrial Revolution, when people were often confined to asylums less for psychological conditions than for being nonproductive workers. “Mental illness and stigma were born together of capitalism,” he said. “Capitalism defined ‘normal’ as someone who was autonomous and independent and produced the most capital. And we stigmatized those who produced the least.”

During his global field work, Grinker has observed how different societies embrace notions of mental illness. In Namibia, for example, he spoke with the father of a young boy who exhibited classic autism traits but was respected in his village for his goat herding skills. When Grinker asked the father if he was worried about who would care for his son after he was gone, the man gestured toward his neighbors and said, “We won’t all die at once.” Through the village’s social support network, “they fashioned a society that accepts differences we shun,” Grinker said.

Still, Grinker is hopeful that stigma is rapidly diminishing. He doesn’t minimize the barriers that remain. In a TED Talk, he noted that 60 percent of Americans with mental illness get no treatment, worse among minorities; suicide is still the third leading cause of death among teenagers; and anorexia mortality rates are as high as 10 percent. But he also sees signs that, as both Freud and Grinker’s grandfather hoped, mental illness is increasingly accepted as a common part of human diversity. Today, for example, 12 percent of American public school children receive some form of special education, he noted, while 10 percent of Americans use antidepressants—as many as take cholesterol-lowering statins.

In his own life, Grinker’s daughter Isabel, 29, self-identifies as autistic, channeling her energy into caring for animals at a research lab. Grinker no longer hears the question he posed to the Namibian father: How will she survive on her own? And in a recent class, one of Grinker’s students described her ADHD diagnosis as the highlight of her freshman year. “Finally,” she said, “somebody saw that I wasn’t lazy or stupid. I just needed a little bit of help.”

“Our ideals are changing,” Grinker said. “We value diversity more than sameness. We no longer worship the person who conforms to an illusion of normality. Normal is becoming whatever someone wants it to be.”

– John DiConsiglio

China’s Leaders: From Mao to Now (Polity Press, 2021)

By David Shambaugh, Gaston Sigur Professor of Asian Studies, Political Science, and International Affairs

Building on nearly 50 years of Shambaugh’s study of China, this book focuses on the idiosyncrasies of five leaders: Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and current Chinese President Xi Jinping. The idea for the volume came to him when he realized that there were individual books he could assign to students, but no catch-all that covered the major rulers from 1949 (when the People’s Republic of China was founded) to the present. With no checks and balances, totalitarian system leaders tend to have oversized impacts, Shambaugh writes, and that is true of “populist tyrant” Mao, “pragmatic Leninist” Deng, “bureaucratic politician” Jiang, “technocratic apparatchik” Hu and “modern emperor” Xi. The latter, the reader is informed, had a difficult upbringing after his father was purged from the party, which may have helped shape his independence. Among the other details we learn are that Xi was criticized as a teenager for feeding dumplings to stray dogs at a time when food was scarce, and there are accusations that his doctoral thesis was plagiarized.

Poems for Your Pandemic (Outskirts Press, 2021)

By Gary Alexander, JD ’67

The author allows that some might balk at a poetic, often humorous, take on the pandemic. But this is ultimately an optimistic volume, though the poems sometimes reflect frustration and anger. One observes that even Santa Claus must follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance; “Yes, this pandemic affects jolly St. Nick,/ The CDC warns: ‘Kids will make Santa sick!’” Of his wife cutting his hair, the author records the barber in hiding (who did a first-rate job), “refused every tip!” Alexander is a lawyer who doesn’t usually write poetry but found penning this volume at midnight gave him much-needed laughs and helped him go back to sleep. The book, which addresses the 1918 flu pandemic, too, notes of a COVID Thanksgiving “a feeling of doom,/ To see your loved ones, you had to use Zoom!”—one of many passages that evoke Dr. Seuss. The latter would likely approve of the poem about scarce toilet paper (“I confess I took toilet paper for granted,/ Weren’t zillions of toilet paper trees planted?”) and the one on a lost mask (“I really loved this mask … it will never, ever be the same,/ My mask is gone, I’ve got no one else to blame!”).

Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival (Lyons Press, 2021)

By Eric Lindner, BBA ’81

Sea tigers may conjure the film Life of Pi, but this gripping tale from 1962—which isn’t for those with aerophobia—centers on Captain John Murray intentionally crashing (or “ditching”) Flying Tiger Line Flight 923 into the stormy Atlantic Ocean after the engines failed. The flight, which had originated in New Jersey, was en route from Newfoundland to Frankfurt. At the time, Lindner writes, flying was 100 times more dangerous than today, and this aircraft had a tendency to erupt into flames. The pilot—with a prior record of near-miraculous flying in tough conditions—tried to save as many of the other 75 people as he could. As one character thinks at the time, “It looks like fireworks. Nothing’s gonna happen. We’re just gonna have a great story to tell.” For those that lived to tell it, the tale is riveting, and the author provides all the context a reader would want—not only during the dramatic events of that day, but also setting up what happened before and after, right up to the present day.

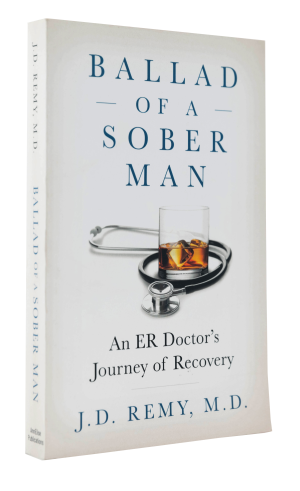

Ballad of a Sober Man: An ER Doctor’s Journey of Recovery (AnnElise Publications, 2020)

By J.D. Remy,* MD ’92

“Successfully getting sober is much like successfully getting wealthy—it’s slow and methodical, and it requires patience,” writes the author in this hauntingly beautiful memoir about losing his house, marriage, medical career and children. After being wheeled into the emergency room where he works, he has to go about the long, hard process of a “wet brain drying out.” The comparison between becoming sober and wealthy is one of many insights he shares, and many readers will wonder how he managed to observe so much during such difficult periods of his life. In a psychiatric ward, he notes many of the medical technicians are named Wayne; he finds echoes of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, Star Trek, The Shining, The Catcher in the Rye and others. Penning the book, he writes, has been “undeniably, a portkey in my recovery journey.” Throughout, there is the refrain: “We are only as sick as our secrets.” *pseudonym

– Menachem Wecker, MA ’09

Photography:

William Atkins