After the Facts

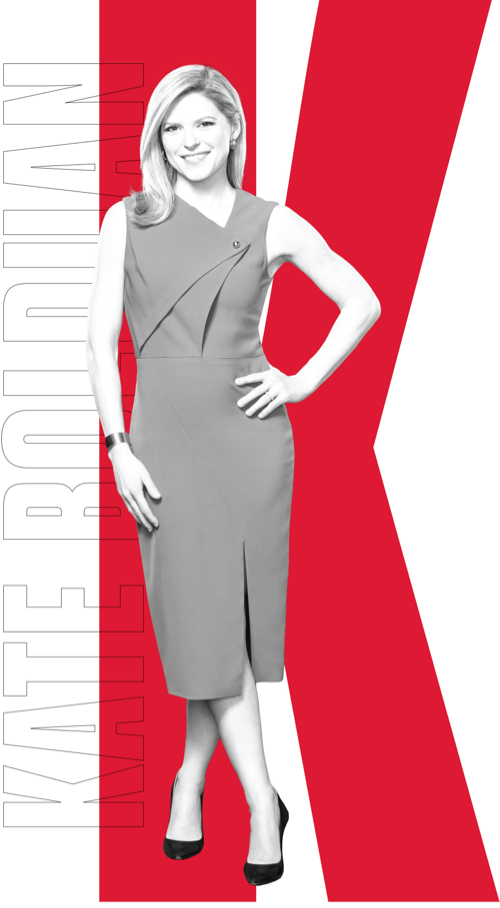

For CNN journalist and alumna Kate Bolduan, the professional is personal.

by Caite Hamilton

You can find anything on the internet these days: an article that supports your idea, an article that contradicts it. Self-help groups. Parenting advice. Whole swaths of people touting the benefits of Ivermectin as a cure for COVID.

And there are a lot of things on the internet about Kate Bolduan, B.A. ’05, CNN’s “At This Hour” host too: clippings on her success from her hometown newspaper, a video of Kate McKinnon parodying her for an “SNL” cold open, a Wikipedia entry that claims she loves ketchup (true) and can water ski barefoot (also true), plus sound bites from recent interviews with politicians, military personnel and even the occasional celebrity.

Most of the time Bolduan, who stands at 5’4”, remains stoic during these one-on-ones, her mezzo-soprano lilt cutting through the noise of a guest’s meandering or even misleading responses. But then there are the clickbait clips of her on YouTube, tearing up with Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.) as they discuss Sen. Joni Ernst’s (R-Iowa) announcement that she was raped in college, or deftly chipping away at the untruths of an of-the-moment political figure. Those clips in particular are too often viewed as a kind of gotcha from media skeptics, evidence of Bolduan as the sort of partisan journalist that should make us stop believing in the news. Instead, they establish her as an empath. A human.

“I have always said that the moment I stopped feeling for the story—the moment I stopped having an emotional connection—is the day I should leave the business,” Bolduan says. “People want that connection and they want you to be impacted by it as much as they are at home.”

But disinformation is rampant and at the center of an international story that reached a fever pitch four days before our interview, when Russian President Vladimir Putin launched a large-scale invasion across Ukraine. CNN’s coverage was, as it tends to be with breaking news, all-encompassing, with correspondents both on the ground in Ukraine and at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. “At This Hour” spent its 11 a.m. time slot answering as many questions about the situation as possible.

Meanwhile, disinformation about the war—and Russia’s role in it—abounded, mainly from inside the Kremlin itself. It comes as no surprise to anyone following the news; soft power is routinely used during wartime to influence outcomes. But the difference this go-round? The internet.

“Disinformation, particularly Russian disinformation, is aiming to create as much chaos and disorder as possible,” said disinformation expert Nina Jankowicz during a Wilson Center panel Bolduan moderated in 2019. “That’s a theme that goes from Estonia right through to Georgia, Poland, Czech Republic and Ukraine certainly. Especially in Ukraine, in fact, it’s trying to inspire a sense of distrust in the democratic system so that people don’t go out and invest in that budding new democracy.”

A free press is a crucial tenet in the democratic system to which Jankowicz refers, and like many journalists, Bolduan asserts that her profession has been more closely scrutinized since 2016 as a direct result of disinformation.

“The job of journalism came under attack in a way that it had never been in my lifetime, with the way that Donald Trump spoke about CNN [and] spoke about journalists,” Bolduan says. In fact, in 2018, Bolduan recalls running down many flights of stairs to evacuate CNN’s New York studio, an active bomb threat underway. “There was this question in the moment of, am I literally in my workplace now under threat because of a lie someone is believing about the motivations of my network?”

Moments like that one rock her, certainly—she placed a frantic call to her nanny that day to make sure her two daughters, now 7 and 4 years old, were safe. After all, she’s only human. But moments like that one motivate her too.

“The more the world feels out of control, I actually feel like the more the world demands good journalists,” Bolduan says. “We need more good journalists to be able to make sense of the chaos.”

And good journalism—at least, her particular brand of it—includes getting personal, by way of just being herself. “I feel the story as well as report on the story,” she says. “That's how I've always been.”

Bolduan was born in 1983 in Goshen, Indiana, a small town in Mennonite country about 45 minutes south of Notre Dame. Her mother, Nadine, was a nurse, and her father, Jeffrey, was (and still is) a practicing urologist. People even call him “Doc,” if that gives you a picture of Goshen’s small-town ethos (its population hadn’t yet crested 20,000 by the 1980 census).

The third of four girls, Bolduan was in many ways a typical Midwestern teenager—attending the public high school, playing on its volleyball team and performing in its musicals. But she was also a bit of an overachiever, becoming editor of the high school newspaper and earning the title of salutatorian for her graduation in 2001 (she reports that she would have been valedictorian were it not for a C- in calculus that still haunts her). She owes her drive, she says, to her parents.

“It was never like they said, ‘You must do this, you must do that,’” Bolduan says. “But we traveled a lot, and that kind of helped open our eyes to the world.” In particular, the family repeatedly went to Mexico, where both her parents had lived before having children and where her dad had attended medical school. “I see that as kind of the beginning of me caring about the world.”

Those high-achieving impulses rubbed off on all of the girls. Bolduan’s sisters each have successful careers—the eldest is a clinical psychologist, the second is an import/export attorney, and “the baby” (“we love to call her that,” Bolduan says) is an ENT on the cusp of opening her own practice.

“I’m probably on the lower end of the achieving scale,” Bolduan jokes. With two parents in the medical field, she did, at one point, have her sights set on a similar path, but things changed after she took a theater class in high school. She got involved in musicals and eventually enrolled at the George Washington University to study musical theater.

Soon after arriving, though, feeling the common pressure of all undergrads to declare a major and decide on her future, she visited her academic adviser, Mark Feldstein. He suggested she combine everything she had found passion in—the high school newspaper, the musicals, traveling—to pursue broadcast journalism.

“It was never anything I had really ever considered,” Bolduan says. “But I jumped into [Feldstein’s introductory broadcast news class] and that’s where it all started for me.” She includes Feldstein; Steven Roberts, GW’s Shapiro Professor of Media and Public Affairs; and Professor Emeritus Carl Stern among the professors who had the greatest influence on her experience at GW—and her career.

“[It was] not only what they taught me in the classroom but the advice outside of the classroom,” she says. “You need to do [journalism] in practice, and these professors—now friends—showed me how.”

Feldstein, currently the Richard Eaton Chair of Broadcast Journalism at the University of Maryland, says he knew right away Bolduan was made for television journalism.

“She clearly had potential to make it big—smarts, curiosity, ambition, people skills, and a great broadcast voice and presence,” he says. “She struggled a bit at first, as all students do, to learn to write broadcast news scripts, which is different from the style used to write for newspapers—broadcasters write for the ear rather than eye—but she picked it up quickly and showed real enthusiasm.”

She took an internship at Dateline NBC, then landed a job at NBC’s D.C. affiliate, News4, where she spent her time “following around [local news icon] Pat Collins” and learning how to do the job of being a reporter. Then, working as a desk assistant without any on-air time, she put together a demo reel—a piece about a panda at the National Zoo, another about distracted driving that she had worked on with Collins and retold in her own words—and sent out 150 VHS tapes to news stations around the country. She heard back from two, one of which was WTVD in Raleigh, North Carolina, an ABC affiliate where Feldstein had once worked as an on-air investigative correspondent.

Bolduan considers that gig her first big break. Her second was the call from CNN Newsource, an affiliate service that she often calls “a bootcamp for correspondents.” She spent her first day on the job, for instance, shooting dozens of live shots on the 2007 Minneapolis bridge collapse. From there, she worked as a congressional correspondent and co-anchored “The Situation Room” with Wolf Blitzer. Six years into her tenure at CNN, she was invited to the big show: a hosting gig launching CNN’s morning show “New Day” from the station’s New York studio. She was 29 years old at the time, breaking a record as the news channel’s youngest morning show host.

“Kate always sparkled. She had a special gift that few have—a natural rapport with a camera and an audience,” says Roberts. “It’s deeply gratifying to see a former student like Kate become so successful, because I know how hard she’s worked to achieve this level of success.”

Currently the sole host of CNN’s “At This Hour” after co-host John Berman left to join “CNN Newsroom,” Bolduan tries to stay open to what comes next. On a macro level, she concedes that the unknown “next” is part of the fun: “The strange, circuitous, cumulative experiences that we have as journalists make us what we are, make us the unique journalists that we become.

“For two years, stories one through five were the pandemic and out of necessity, that’s what it was,” she says. But there’s more out there. There are so many more stories to be told.”

And Bolduan wants to tell them all. She’s interviewed families in Newtown following the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, conducted the first TV interview with then presidential candidate South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg and his husband, Chasten, and covered the O.J. Simpson armed robbery case. When asked what her dream interview would be, she doesn’t hesitate.

“You’re always thankful to interview the president of the United States,” she says. “But the most important interviews—I truly mean this—the most memorable interviews that I’ve ever done are everyday people who we come across in the most extraordinary moment of their lives and they allow you in. If I flip it forward, my dream interview is truly just another, the next person I get to interview who lets me into their lives in an extraordinary moment to tell their story.”

Photography: Mary Ellen Matthews // Adam Rose // John Nowak