Sky High

WNBA All-Star and GW alumna Jonquel Jones is living her dream—and her truth.

Story // Steve Neumann

Jonquel Jones first began to love basketball when she was knee-high to her current 6-foot-6 frame. She became mesmerized by the action in the paint at the practices of the boys’ high school team that her father coached.

All the hooting and hollering as the players repeatedly drove to the hoop inspired Jones, B.A. ’19, who would go on to be a Women’s National Basketball Association MVP.

When she got a glow-in-the-dark basketball one Christmas, Jones promptly took the bottom out of an old milk crate, nailed it to a piece of board and put it up on a pole on the street outside her home in the Bahamas.

“I remember just getting shots up with that and learning how to shoot,” Jones says. “As I got older, I realized I could make a career out of it—if this can be a job, it’s a job I want, you know?”

Jones did eventually turn her first love into a career on the court, and a wildly successful one at that. Today, the 29-year-old is in her seventh season in the WNBA and in May began her first season with the New York Liberty as a power forward.

Jones was the sixth pick in the 2016 draft, signing with the Connecticut Sun. In her second season in the WNBA, in 2017, she led the league in rebounds, was named the league’s Most Improved Player and was selected to her first All-Star team. In 2021, she was the league MVP.

“I remember just getting shots up and learning how to shoot. As I got older, I realized I could make a career out of it—if this can be a job, it's a job I want, you know?”

ESPN analyst Monica McNutt, who was born and raised in Prince George’s County, Md., where Jones played high school ball, calls Jones a “force” and has been following her career since high school.

“I remember when she was at Riverdale Baptist in high school as just another kid coming out of Prince George’s County area hooping,” McNutt says. “She’s a presence in the paint, but she can also draw slower-footed defenders away from the rim to knock down a three-ball.

“It’s just really been incredible to watch her game grow and evolve,” she adds.

Jones seems to be able to do it all on the court: She can dunk, rebound, block shots, drop dimes—that is, assists—and, as McNutt says, make three-point buckets with ease. She became a force on the court by putting in long hours starting in high school.

Jones began her basketball career in the U.S. at Riverdale Baptist School in Maryland under head coach Diane Richardson. One of Richardson’s former players—Jurelle Nairn, who is also from the Bahamas—told her there was a player who wanted to come over to the States to play. After some soul searching by both Richardson and Jones’ family, Richardson became Jones’ legal guardian so the future All-Star could enroll and play at the school.

The transition from the Bahamas to the U.S. wasn’t easy for Jones. She was nervous about being “the new kid” playing in an unfamiliar athletic, cultural and social environment, and she hadn’t hit her growth spurt yet.

“I called her spider,” Richardson says. “She was much smaller then and skinny, of course.”

When Jones first landed in the U.S., she went straight from the airport to her first practice with Riverdale Baptist, where the style of game was much different than what she was used to.

“She was probably one of the better players coming out of the Bahamas, but at my high school, we were pretty skilled and pretty fast, so she was kind of like a deer in headlights at first,” Richardson says.

But, Richardson says, Jones was also like a sponge: The more she gave her, the more she did. She was like the storied postal worker—neither rain nor snow could keep her from putting up buckets.

“I told her, ‘I've coached some pretty good players in my time, so you gotta be good,’” Richardson recalls.

As a result, Jones would grab a ball and just shoot and shoot and shoot every chance she got, spending at least eight hours a day working on her game.

LEFT New York Liberty forward, Jonquel Jones.

ABOVE Members of the Bahamian Consulate with Jones.

LOWER Jones during her time on the GW Women's Basketball team.

But while Jones was hard at work honing the skills that would later earn her a spot in the WNBA, she was struggling off the court to reconcile her identity as a lesbian with the faith she grew up with and the traditions of her home country.

Jones was raised as a devout Christian in the Bahamas, a country where same-sex relationships were illegal until 1991 and where discrimination based on sexual orientation is still common.

Not wanting to choose between her sexuality and her relationship with God, she decided to instead focus all her attention on basketball.

That focus caught the attention of Division I scouts, and Jones ended up attending Clemson University in the fall of 2012. Once she got there, however, her experience didn’t match her expectations.

“The only thing in [the city of] Clemson is the university, literally,” Jones says. “You had to drive 40 minutes to even go to the mall—and that was a new experience for me.”

Disenchanted, Jones transferred to GW halfway through her first year. She had played summer pickup games at GW while she was at Riverdale Baptist, so she knew the D.C. area well. Moreover, Richardson had just joined GW as an assistant coach, and one of Jones’ former high school teammates, Lauren Chase, was coming in as a point guard.

“Coach Richardson was my high school coach and my guardian, so I knew I would be in good hands,” Jones says. “And I knew the level that Lauren could play at, so it would be nice to be able to play with her again, too.”

While at GW, Jones continued to focus on her game, again under the tutelage of Richardson.

“Sometimes she would be so unselfish and make that extra pass because we had so many good players on that team,” Richardson says. “But there were times when she would be an absolute monster, a beast on the board—she would get that rebound and kick it back out.

“She was a major part of that program, for sure,” she adds. “She brought so much energy to the team; they just couldn't wait to get on the floor to win games.”

Jonquel Jones looks around the New York Liberty locker room at Barclays Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., on Jan. 20, 2023.

When Jones finally got the chance to bring that energy to attacking and defending the lane in the WNBA, she also saw a lane open for her in her personal life.

“I saw people that were happily married, people that were in very healthy relationships, people that were single and enjoying life,” Jones says, “and it just gave me that reassurance of knowing that it will be OK. I knew I was going to be able to live my truth and still be myself.”

But just as she started to feel satisfied personally, Jones began to feel unsatisfied professionally off the court. She had hoped that leading the league in rebounding, averaging 19 points per game, earning the MVP title in the 2021 season, as well as being asked to appear in a State Farm commercial, would lead to more marketing opportunities and monetary benefits—but it didn’t.

Jones believed she was being passed over for those opportunities because of who she is: Black, gay and self-described as more masculine—and outspoken about all those things.

“She's not wrong in her assertion,” McNutt says. “The league is made up of largely Black women, and a strong percentage happens to be members of the LGBTQ+ community, but these are intersectional identities that, to Jonquel’s point, are not often celebrated.”

Jones has received some encouragement recently, most notably from Nneka Ogwumike, the president of the WNBA Players Association.

“She told me, ‘You don't understand how much being vocal about how you feel can really change your life and your opportunities,’” Jones says. “A perfect example was the State Farm commercial—I probably wouldn't even be able to say that I was in the commercial if I hadn’t decided to speak up on social media.”

But while there are still frustrations on the professional front for Jones, things keep getting better in the personal sphere.

“My relationship [with my family] has been way more seamless than I thought it was going to be,” Jones says. “I was terrified to [come out to] my dad. I thought he was going to be the toughest person to have a conversation with. I put it off for years.

“But he’s been amazing,” Jones adds. “He gave me the reassurance I really needed that everything would be OK. He genuinely cares about me and my sexuality, and about my girlfriend and how we’re doing.”

While the long, hard road from a homemade basket on a street in the Bahamas to the polished hardwoods of the WNBA was well worth the effort, this past year has shown Jones that perseverance in her personal journey also has its own rewards.

“This last Christmas was the first time in my life I brought a girlfriend around extended family,” Jones says. “It was very nerve wracking just thinking about it. But when the moment happened, people just understood and accepted it—and that’s all I can really ask for.”

With that personal milestone behind her, professionally Jones is looking forward to continuing to refine her game with her new teammates on the New York Liberty.

“I feel like ever since my MVP season, there’s been so many bodies thrown at me,” Jones says. “So coming on the team with shooters like Sabrina [Ionescu] and scorers like Betnija [Laney] and assists leaders like Sloot [Courtney Vandersloot]—it’s just so many different people that can do so many amazing things.”

Jones was also back in the D.C. area on May 19 for the Liberty’s first game of the season against the Washington Mystics.

“My time at GW was amazing, so every time I'm in the city, I go back,” adds Jones, who left GW in 2016 to pursue a professional career but later returned to complete her degree. “I may not announce myself, though, because I like to just go and walk around campus and be nostalgic.”

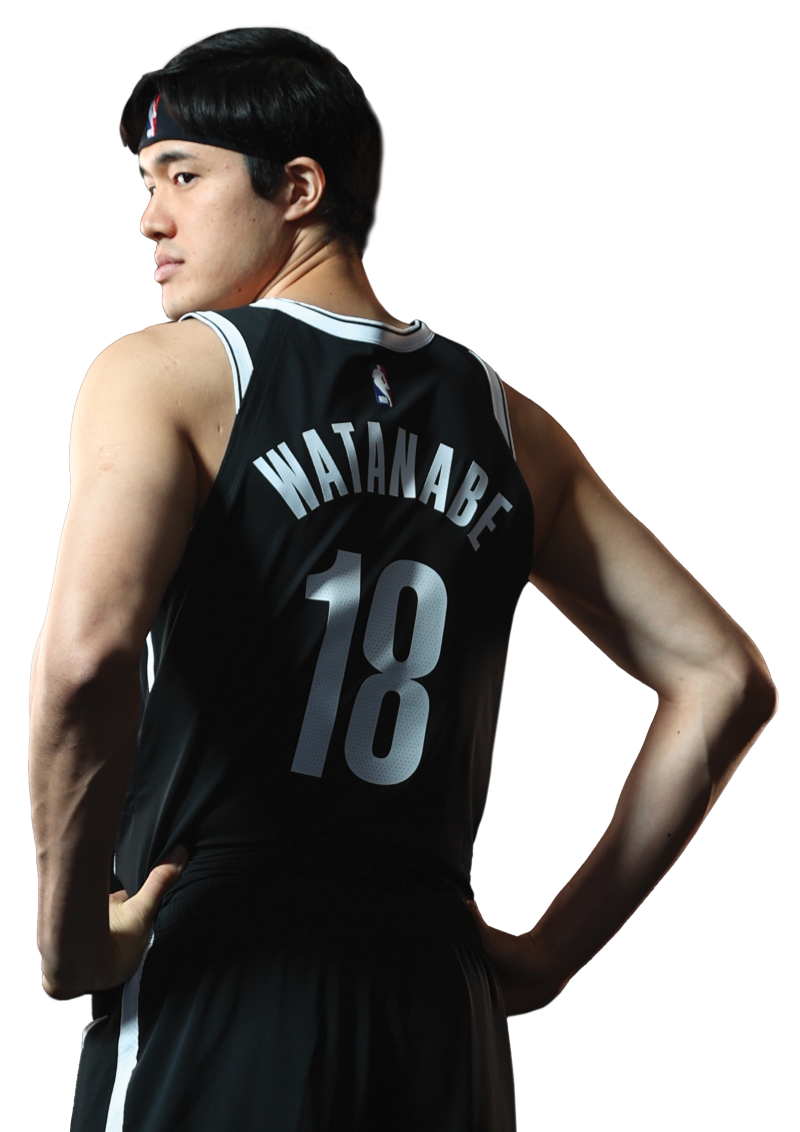

BLAZING A TRAIL FROM KAGAWA TO THE NBA

Yuta Watanabe is showing younger generations of Japanese basketball players that it's possible to excel in the NBA

Yuta Watanabe, B.A. ’18, only the second Japanese-born player in the NBA, couldn’t miss.

It was last November on the hardwood in Brooklyn’s Barclays Center when Watanabe nailed four three-point shots to help cement the Nets’ victory over the Memphis Grizzlies.

The crowd gave him a standing ovation.

Watanabe, a 6-foot-8 forward, was among the NBA’s most accurate three-point shooters during the regular season, making more than 44%.

His marksmanship has earned him praise from his then superstar teammates Kevin Durant (“his fundamentals look perfect”) and Kyrie Irving (“best shooter in the world right now”) as well as the nickname “Yuta the Shootah.”

He’s also known to be a fierce defender who knows how to be in the right place at the right time.

It has taken a lot of practice and patience. The Nets are the third team he’s played for in five years.

“I'm glad I’m in the league right now, but there were times when even though I was working hard, it felt like it wasn’t paying off,” says Watanabe, who played for two years each with the Memphis Grizzlies and the Toronto Raptors before signing with the Nets in 2022. “But in the end, it did.”

Playing in the NBA is pretty much all he’s ever wanted since his days watching the LA Lakers as a boy. Realizing that dream has taken him from Jinsei Gakuen High School in Japan to GW’s Smith Center to the Barclays Center in Brooklyn.

Watanabe was born and raised in Kagawa, Japan. Both of his parents as well as his older sister played professionally in Japan. His parents were also his first coaches.

As a teenager, Watanabe earned a spot on the country’s national team, and a Japanese newspaper dubbed him “the Chosen One.” After years of watching recorded NBA games (they were on too late to watch in real time), he had his sights set on the U.S. and playing in the league.

His favorite player? Kobe Bryant, whom he grew up idolizing. But another NBA player made his dream feel possible: Yuta Tabuse, who in 2004 became the first Japanese player in the NBA when he took the court for the Phoenix Suns.

“I was screaming,” Watanabe told “The Washington Post” in 2018. “It was so amazing.”

Watanabe came to the U.S. in 2013 to finish high school at St. Thomas More Preparatory School in Oakdale, Conn. The following year, he became the first Japanese-born player to earn a Division I scholarship when he came to GW.

He made history again in 2016 when, as a sophomore, he helped the GW men’s basketball team win its first postseason championship, claiming the NIT crown with a 76-60 victory over Valparaiso at Madison Square Garden. Two years later, Watanabe was named the A-10 Defensive Player of the Year.

For Watanabe, the hard work required to play basketball at a Division I school involved more than the daily slog of half-court wind sprints, endless box-out drills and repeated jump shots. As an immigrant, Watanabe also had to navigate a culture and a language that other student-athletes were able to take for granted.

So, on top of his basketball practice and regular coursework, Watanabe attended English tutoring sessions multiple times a week. Between classes, practices, homework, tutoring and extra gym workouts, a typical day at GW for Watanabe usually ended around 10 or 11 p.m.

“No matter what I was doing, I always went back to the gym and got some shots up,” Watanabe says. “I just told myself that’s something I have to do every day, no matter what.”

His dedication didn’t go unnoticed.

“His work ethic, perseverance and passion wouldn't let him fall short of achieving his basketball dreams,” says Brian Sereno, associate athletics director for communications at GW.

“His ability on the basketball court is only topped by the person who Yuta is. He’s so focused and serious with everything he does, but he smiles so easily, which is infectious and makes him so easy to root for,” he says. “He's a true fan favorite wherever he goes.”

Watanabe, who in July signed a one-year contract with the Phoenix Suns, now has near rock-star status in Japan where he is one of the nation’s top athletes and his NBA jersey is a perennial top seller.

It’s important to Watanabe to pay it forward by showing aspiring Japanese basketball players a path ahead.

“Before I left Japan, I said I wanted to be a pioneer so that the younger generation can follow me,” Watanabe says. “And I think I played that role because now I see a few Japanese players playing in the NCAA.”

He also has lots of fans closer to home, including fellow GW alum and New York Liberty forward Jonquel Jones, whose time at GW overlapped with Watanabe’s.

“When Yuta was at GW, I used to call him Wasabi Watanabe, because I felt like he would catch on fire—he'd just be killing it on the court,” Jones says. “I’m happy to see somebody from GW in the same place that I’m in, and just being really successful.

“Every time he makes a bucket, I turn to somebody and say, ‘I went to GW with him!’”

| Jones: Courtesy of the New York Liberty, GW Athletics Watanabe: Nathaniel S. Butler, Getty Images |