Legally Bound - Winter 2016

(Photos: William Atkins)

Inside the Jacob Burns Law Library's trove of 35,000 rare books.

By Matthew Stoss

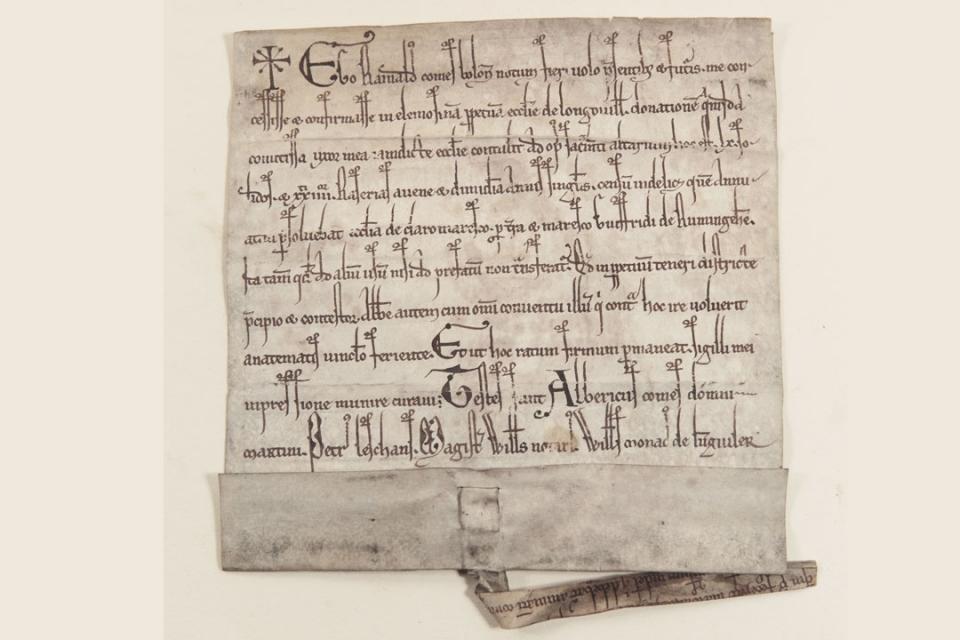

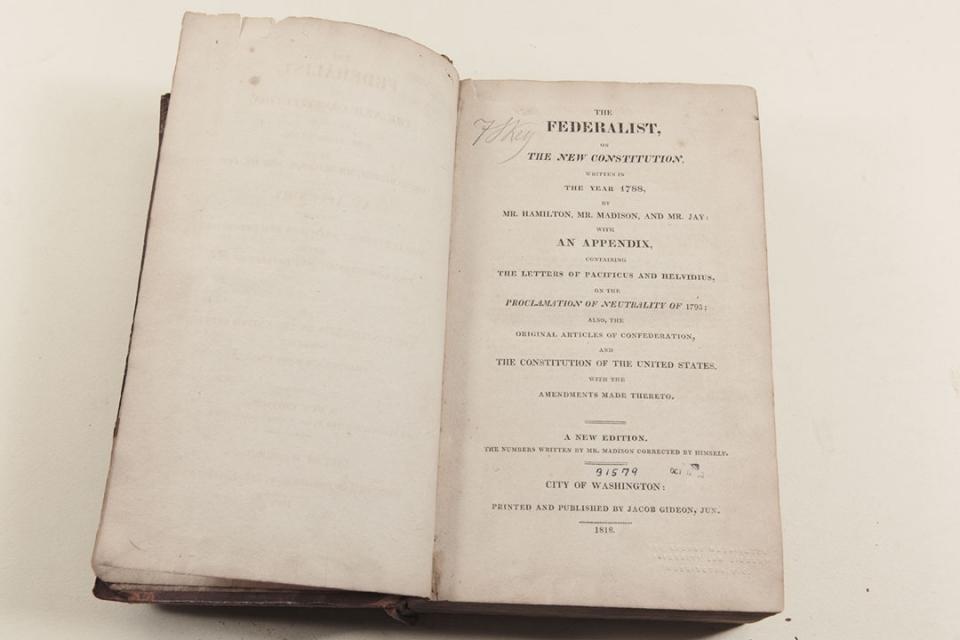

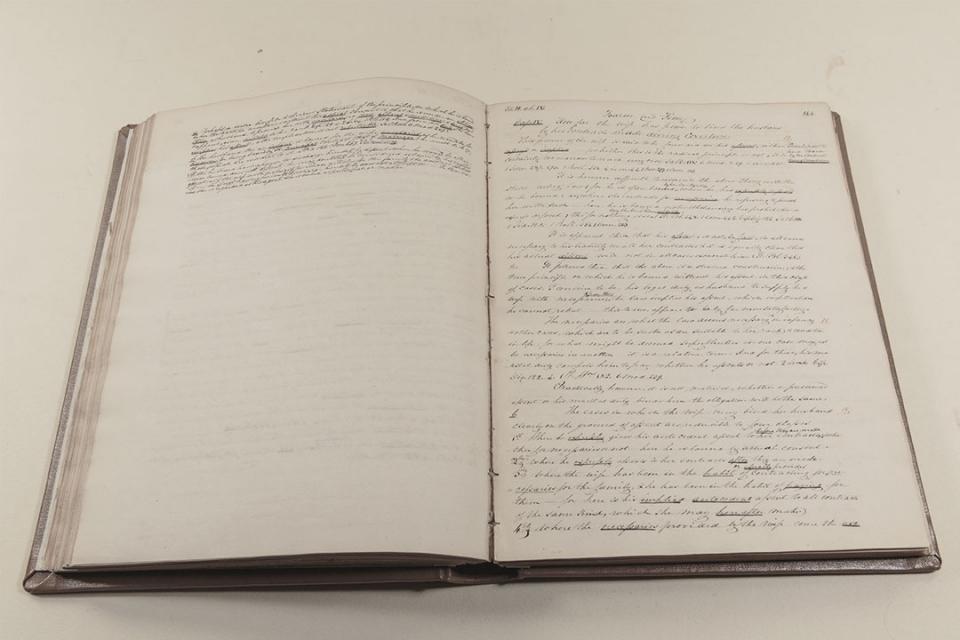

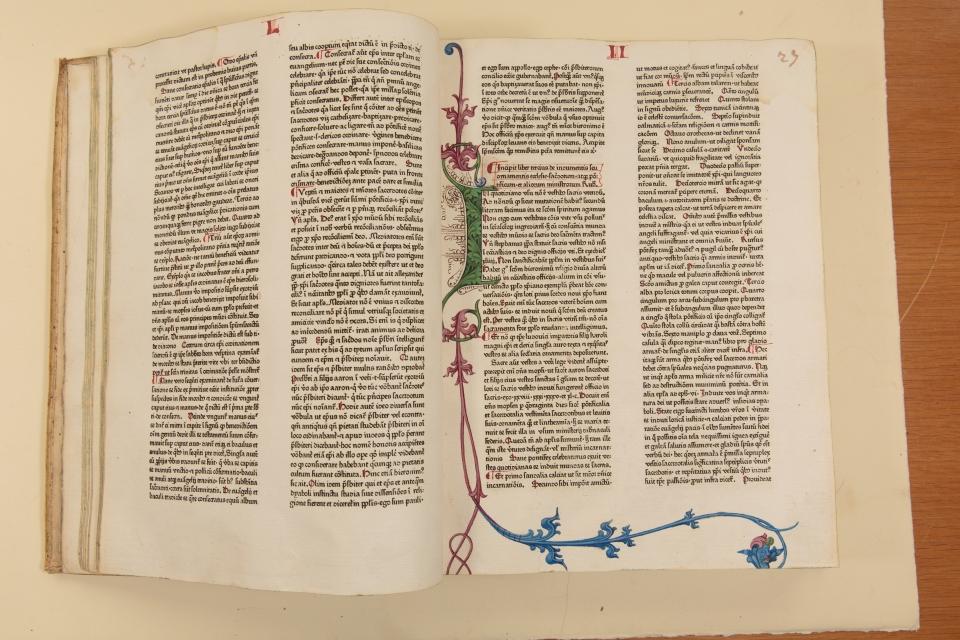

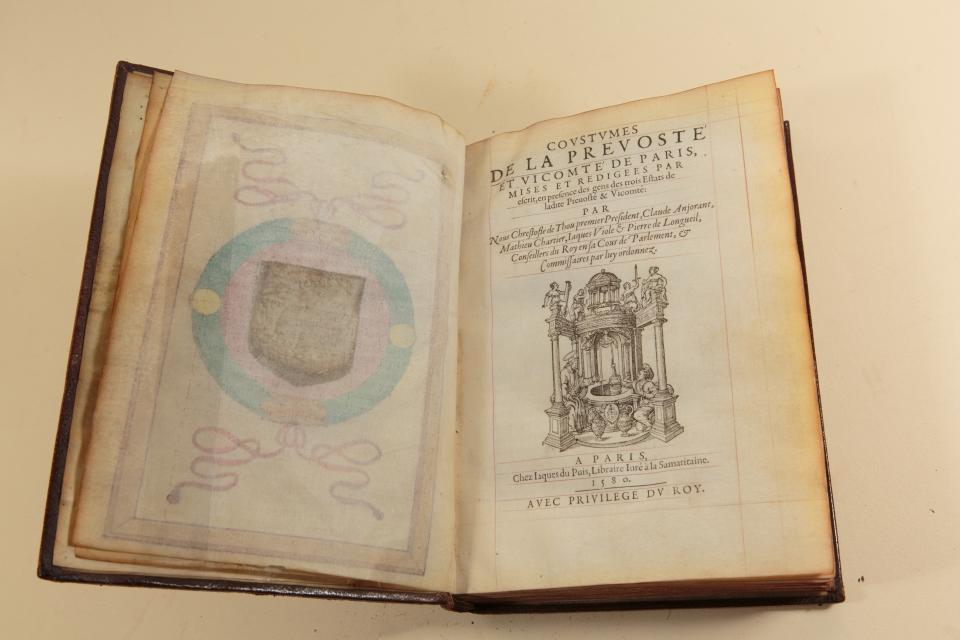

Behind a plain basement door in the Jacob Burns Law Library, which in any other building would lead to a janitor's closet or an industrial unisex bathroom, are about 35,000 rare books and manuscripts. Some of the books are old enough to be within living memory of Johannes Gutenberg. Those are the incunables—books printed before 1501. The manuscripts are even older.

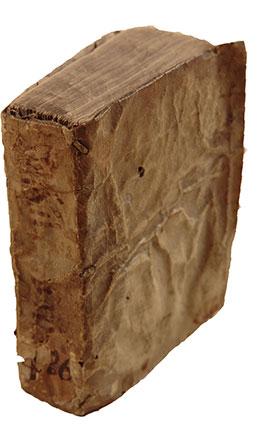

Among the books are 15 editions of the Malleus Maleficarum—the "Hammer of Witches" in English—and among them is an abused, annotated travel-size grimoire-looking copy from 1495.

It's Associate Dean for Information Services and Director of the Law Library Scott Pagel's favorite piece in the rare-book collection that he and Director of Special Collections Jennie Meade have, through auctions, book fairs and eBay, built out over more than two decades from a single glass-enclosed bookcase.

Written around 1486 in Latin by Heinrich Institoris, a priest and college professor, the Malleus dealt with witchcraft and demonology and was the definitive handbook for detecting, trying and executing witches for nearly 300 years.

"For example, if a witch is being brought into a courtroom," Mr. Pagel says, "the witch must be brought in backwards because if the witch sees the judge before the judge sees the witch, the witch has control over the judge."

The Malleus Maleficarum has been described as "the most portentous monument of superstition which the world has ever produced." Mr. Pagel just calls it "evil." As for why it's his favorite? It's the history.

"You can almost palpably sense that somebody used this book," Mr. Pagel says. "And what they were using it for was wrong. And that's one of the books that to me is the most terrible and the most meaningful."

The Malleus is important in the Burns library rare-book collection because it deals so flushly with the intersection of church and state law, a topic of particular significance to the library.

"If the church found somebody guilty, they couldn't execute them," Mr. Pagel says. "They had to turn them over to the state to execute them, so it's basically the state doing the bidding of the church."

If it seems esoteric, it is. But that's the point. Only a small handful of university law libraries in the country have a collection as extensive as GW's. Mr. Pagel wanted a research library, not a museum, that would attract scholars from all over—something like they have at Columbia University, where Mr. Pagel had one of his first librarian jobs and where he would spend his free time perusing the rare-book stacks.

Asked why this means so much to him, Mr. Pagel tells a story about a researcher going to the Athenaeum library in Boston.

"He's looking for a very specific edition of a book and he's just amazed they have it there," Mr. Pagel says. "They get it from the stacks and they bring it to him, and he asks the librarian, 'Who did they buy this for?' And the response is, 'Well, they bought it for you.'

"The idea is that, someday, somebody will want this book and it will be there waiting for them, and that's the idea of a true research library. You're not necessarily buying for today's users, but you know that somebody, someday will want it and you'll have it for them. I don't know who will want the Malleus Maleficarum from 1495, but when they do, we will have it for them."

More Alumni News

The Sweet Life

Behind the newly named Honey W. Nashman Center for Civic Engagement and Public Service is an American story more than a century in the making.

Fluid Dynamics

As a child in the 1950s, alumna Alexandra "Alex" Tolstoy created oil sketches of Rembrandts and of angels in Michelangelo paintings.

How To Sound Smart About Architecture ...

And impress friends, significant others, your parents who didn't want you to get that liberal arts degree.