Bookshelves

Bookshelves

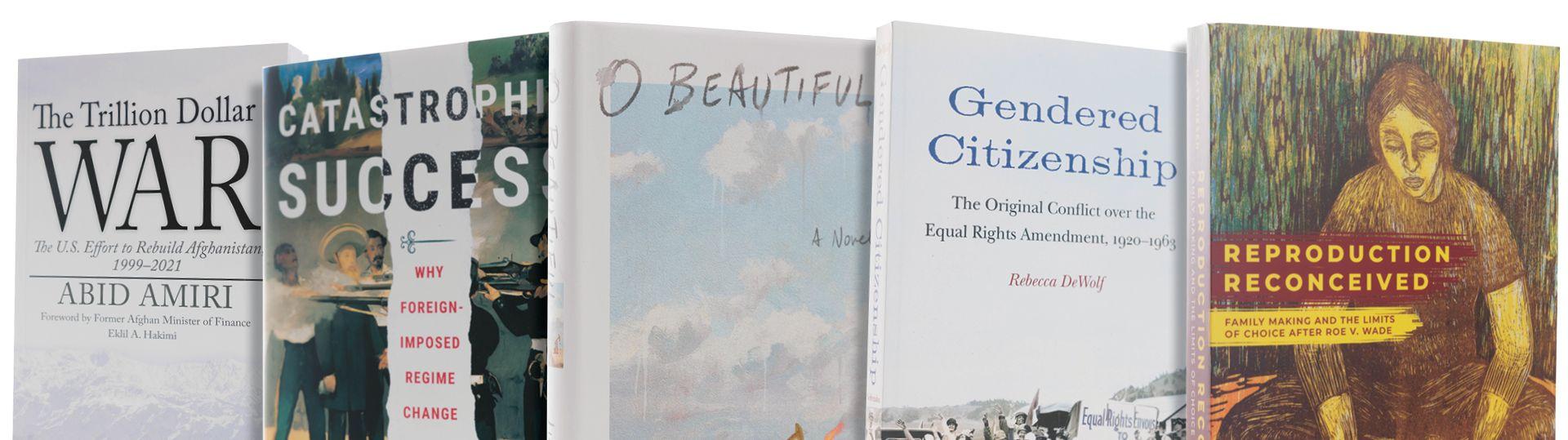

Jung Yun Draws on Her Experience and Nose for Storytelling—Not Biography—to Craft ‘O Beautiful’

Many presume erroneously that Assistant Professor of English Jung Yun’s novels are autobiographical. “I get that question at least once a week,” she tells “GW Magazine.” “At least my parents aren’t implicated this time!”

The Seoul-born and Fargo, N.D.-raised author was mortified that many assumed her first novel, “Shelter,” whose protagonist is a Korean American man with elderly, abusive parents, was about her family. “It felt like I had indicted my parents in something they weren’t involved in, simply by writing a work of fiction,” she says.

O Beautiful (St. Martin’s Press, 2021) By Jung Yun, assistant professor of English

In her new novel, “O Beautiful” (St. Martin’s Press, 2021)—the protagonist was raised in North Dakota by an American father who met her Korean mother while he was stationed overseas—some readers have tried to connect dots between the main character and Yun. “But that’s all they really are. Tiny dots.”

The author does draw from her experience when crafting fictional characters, whose contours she delineates beautifully. One is “short and snowman-like, composed mostly of circles.” Another sits in his office as if “he’s trying to wall himself in behind a fortress of folders and envelopes and boxes.”

“Something I always tell my students is that writers notice. We observe,” Yun says. “We’re constantly expanding our catalog of ideas and images and descriptions, hoping for the next opportunity to put some of them into play.” She maintains and draws upon a “mental inventory,” and somewhere, she is sure, she observed a man who seemed composed of circles.

“I’ve long since forgotten who that man was and where I saw him, but I’ve never forgotten that particular physical quality,” she says.

In between gripping character details is a sobering and difficult yet ultimately uplifting story of a 40-something model turned writer, Elinor, who tries to find her place in a hostile world of men who either want something from her or to erase her or both. A freelance assignment from a “New Yorker”-like magazine in hand, Elinor tries to understand what is happening in Avery, N.D., which is experiencing an oil boom-fueled economic transformation. She finds scoops and unexpected wrinkles not only in the story she pursues but also in her life and even in the plum assignment.

In some ways, Elinor has a very well-honed moral compass, but she is also flawed and in need of her own redemption, which comes just in the nick of time, it seems.

Yun stresses that she is not penning didactic fiction, nor can she control readers’ reactions to her work, but she also would not mind if readers take lessons of empathy and tolerance away from her novel.

“The best and most I can do is craft a life that feels real and full on the page, and then hope that a stranger might be inspired to an emotion or an action as a result,” she says. “Introspection, empathy, reexamination of past events and past behaviors—these are all the things that Elinor does as a result of her time in the oil fields. If a reader is inclined to do the same, then that’s wonderful but not my goal.”

One of the gripping aspects of this novel is its own journey. Initially, Yun had a collection of interconnected short stories in mind. After completing seven, each with a male protagonist, she was sure she was headed in the wrong direction. “That’s a really terrible sign—when the writer isn’t even interested,” she says.

Visiting her parents in North Dakota and talking to people at oil fields, she was drawn to women’s stories and grew convinced she needed a woman at the center of her book. She plucked Elinor from what would have been the eighth story and moved her to center stage. Without spoiling “O Beautiful,” suffice it to say that in this sense, form follows content.

Catastrophic Success: Why Foreign-Imposed Regime Change Goes Wrong (Cornell University Press, 2021)

By Alexander B. Downes, associate professor of political science and international affairs

Many powerful leaders who try to replace a rival government with a puppet or other aligned leadership find their efforts frustrated. Regime change, according to this book, tends to trigger further conflict—both internally in the overthrown country and between the new leadership and the intervener. It notes the 2001 toppling of the Taliban was Afghanistan’s sixth regime since 1839, which made it second only to Honduras, which had the unenviable distinction of eight foreign-imposed regime changes in 200 years. Would-be interveners are better off “not owning the problem,” per this book. “Regime change may appear to be a quick and easy solution, but over the longer term it turns out to be neither easy nor a solution.” That strategy should be reserved for very rare and exceptional cases, the author writes.

Gendered Citizenship: The Original Conflict Over the Equal Rights Amendment (University of Nebraska Press, 2021)

By Rebecca DeWolf, B.A. '04, M.A. '08

The 99-year-old Equal Rights Amendment has seemed, at times, poised to persist, but it remains a proposal. This book notes Equal Rights “emancipationism” and “protectionism” did not separate along political divides from 1920 to the 1960s. It was only after 1970, when many differentiated between gender and sex, that it followed partisan contours. To the author, the amendment’s original conflict laid the groundwork for ensuing decades by questioning the nature of U.S. citizenship. Protectionists sought to afford women special rights, which they believed provided extra protection, while emancipationists argued for equal treatment in all regards for men and women. “The original era conflict is best understood as a battle between competing civic ideologies and not mainly as a struggle between divergent feminist ideologies,” the author writes.

“The Trillion Dollar War: The U.S. Effort to Rebuild Afghanistan” (Marine Corps University Press, 2021)

By Abid Amiri, M.A. ’15

Despite hundreds of billions of dollars in U.S. aid flowing to Afghanistan, studies show the latter is rife with corruption, unemployment and violence. (One data set found the total bribes paid in Afghanistan in 2018, $1.65 billion, represented 9 percent of its gross domestic product.) The author, whose family fled violence in Afghanistan for Pakistan, worked at the Afghani Embassy in Washington before obtaining his master’s in international development at GW. Supplies branded with U.S. aid institutions’ logos remain fresh in his mind (as do experiences with Taliban brutality), which informs his argument that Afghanistan needs to help itself. “The main reason I am so passionate about getting development aid right is that development aid is so very personal to me,” he writes, “as I have come out of the conflict zone successfully due to the help I received from aid agencies.”

“Reproduction Reconceived, Family Making and the Limits of Choice after Roe v. Wade” (University of California Press, 2021)

By Sara Matthiesen, assistant professor of history and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies

To most people, the term “reproductive politics” refers to abortion, but this book argues motherhood (“family making”) requires close examination for its unpaid labor (“labor of love”) undergirding the economy. After Roe v. Wade in 1973, newly empowered mothers also bore motherhood’s responsibilities and costs. “Having a family has become harder and costlier since the 1970s—especially for those who built families on the economic, racial, and sexual margins of society,” the author writes. Factors to blame include disease, mass incarceration and discrimination, which collectively, to the author, “debunks the myth of choice inaugurated by Roe.”

– Menachem Wecker, M.A. ’09

Photography:

William Atkins