Bookshelves

Bookshelves

‘Up With the Sun’ Reimagines a Toxic Life—and its Violent End

Professor Emeritus Thomas Mallon’s new novel is the always witty and at times poignant tale of Dick Kallman, a real-life actor and mostly closeted gay man who was perhaps the living embodiment of being one’s own worst enemy.

By Thomas Mallon

“Up With the Sun” chronicles three decades of ups and downs in the life and career of Dick Kallman—abrasive, showy and off-putting but not untalented in Mallon’s portrayal—from his first role on Broadway in 1951 to his final days in 1980 as a questionable dealer of even more questionable antiques. Mallon alternates Kallman’s relentless trajectory with chapters narrated by a foil, a gentle pianist named Matt Liannetto who is becoming increasingly at ease with his identity as a gay man. (The two cross paths multiple times.)

Kallman’s apex is a starring role on “Hank,” an improbable 1960s sitcom in which an orphan disguises himself as various college students in order to attend university classes. (High jinks generally ensue.) The nadir is his violent murder, along with that of his lover, during a robbery of Kallman’s gaudy Manhattan townhouse. Along the way, we see Kallman bluster, brag, backstab and even slam a costar’s finger in a stage prop mid-performance.

It’s a somewhat different subject for Mallon who has written 11 previous historical novels mainly centered in Washington, D.C., and on its leaders, including “Watergate,” which was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award, and “Fellow Travelers,” which has been adapted for a Showtime series that debuts this year.

“GW Magazine” talked to Mallon, professor emeritus of English, about “Up With the Sun,” what drew him to Dick Kallman and the responsibility of writing about real people.

Q: Dick Kallman—unlike many of the subjects you write about—isn’t a household name (despite his very best efforts). What made you want to write a book about him?

A: I watched his short-lived sitcom, “Hank,” when I was in the ninth grade. I wanted to go to college desperately, as did the character he played. The premise of the show was pretty risible. The character Kallman played had no money and did constant odd jobs on campus; when he knew a student would be absent from a class he was interested in, he’d disguise himself as that student—and try to remain one step ahead of the registrar.

My father, who had had to leave school after the eighth grade, would watch with me—just as we used to watch the quiz show “College Bowl” together on Sunday afternoons. I’m sure that all the time he was watching, he was wondering how he was possibly going to afford to make my own collegiate dreams happen. Bad as it was, “Hank” stuck with me and, weirdly, Kallman was murdered in 1980 on the day of my father’s funeral.

Q: Where does the title come from?

A: It’s in the first line of the theme song from “Hank.” The lyrics, by the great Johnny Mercer, were probably the most distinguished feature of the show.

Q: With the caveat that the book is fiction, what responsibility do you feel to portray real people accurately or empathetically?

A: Empathy is a novelist’s most important requirement. It’s different from sympathy, though it doesn’t exclude that. It’s the ability—whether you’re writing in the first person or the third person—to imagine things from the point of view of a character, whether the figure is based on an actual person or largely made up. I don’t believe a novelist should take gratuitous liberties with real people who are dead, but he has to be able to extrapolate, plausibly and dramatically, from the actual records of those lives. The portrayal of Kallman in this novel is harsh (with a few moments of sympathy), but it was based on the considered recollections of a number of people.

Q: You capture the zeitgeist of the early ’80s with the AIDS epidemic looming. Was it important to you to write about the era and its essential tragedy for almost an entire generation of gay men?

A: Very important. I lived through much of the 1980s in New York and lost many friends to the disease. Last December, I published a selection of my diaries from that time and place in “The New Yorker” (“The Very Heart of It,” Dec. 6, 2022, issue). I intend to do a whole book of those diaries soon.

– Rachel Muir

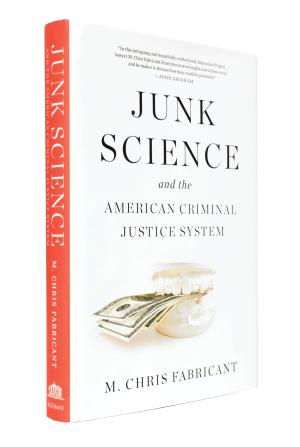

“Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System” (Akashic Books, 2022)

By M. Chris Fabricant, J.D. ’97

Fabricant, an attorney with the Innocence Project, turns an unflinching spotlight on the so-called expert forensic witnesses that juries rely on to inform their verdicts. The book tells the story of three prisoners convicted of capital murder based on what Fabricant dubs “junk science” and the Innocence Project’s fight to overturn their wrongful convictions. Fabricant provides an insider’s view of a criminal justice system that is inherently unfair, broken and racist, and characterized by wrongful convictions, corrupt prosecutors and quackery masquerading as science.

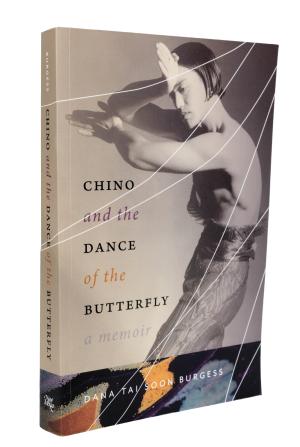

“Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly” (University of New Mexico Press, 2022)

By Dana Tai Soon Burgess, professor emeritus of dance

The renowned dancer and choreographer traces his artistic influences back to his early life in New Mexico and shows how his background and identity as a Korean American gay man shaped his creative vision. The deeply personal memoir is also a testament to the power of dance and art. “Dance has allowed me to externalize my internal world, to clarify and form my identity,” Burgess writes. “Dance has swept me along an odyssey to kinesthetically interpret and express my reactions to the stages of life, to find peace and joy within myself as a bullied outsider, a gay Korean American choreographer from Santa Fe, New Mexico.”

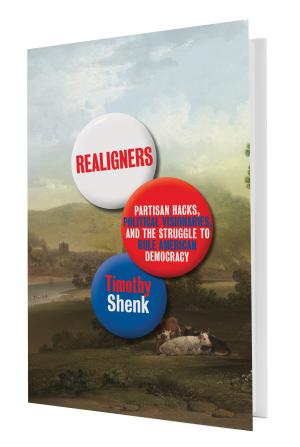

“Realigners: Partisan Hacks, Political Visionaries, and the Struggle to Rule American Democracy” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)

By Timothy Shenk, assistant professor of history

Shenk’s book is a biography of American democracy told through historical figures who succeeded in something that seems impossible today: building coalitions that bind millions of people together in a single cause. He focuses on profiles of the famous (James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, who worked together to forge a Constitutional consensus) and the footnotes (anti-slavery Sen. Charles Sumner and anti-feminist firebrand Phyllis Schlafly, who both reshaped the Republican Party a century apart). Each portrait tells a story about how to maintain popular majorities—and how to lose them.

“A Daughter's Kaddish: My Year of Grief, Devotion, and Healing” (Wonderwell, 2022)

By Sarah Birnbach, B.A. ’71

Birnbach commits to reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish—a Jewish ritual historically reserved for sons—twice a day in synagogue for 11 months for her beloved father. She does this despite the fact that she has not been well schooled in Judaism, that she is a single mother and that her father asked her to hire a man to do it. During the year, she is met with objections and indifference but more often kindness. She gains a new grounding in religion and mindfulness, a sense of purpose and community, and the ability to console other mourners. “When I began sitting Kaddish for my father, I did not anticipate the degree to which the practice would become a lesson in how to live,” Birnbach writes.

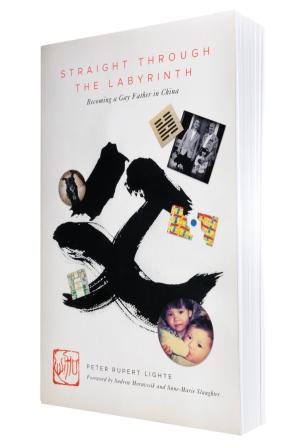

“Straight through the Labyrinth: Becoming a Gay Father in China” (Acasual Books, 2022)

By Peter Rupert Lighte, B.A. ’65

Lighte, a China scholar and founding chairman of J.P. Morgan Chase Bank China, chronicles his quest for fatherhood and the maze he and his husband had to navigate to adopt a child as Hong Kong reverted to Chinese control in 1997. After seemingly insurmountable bureaucracy and drama, he succeeded, becoming the first gay man to adopt a Chinese child in Hong Kong. Lighte also writes about the no-less-challenging adoption of his second daughter. “There was no way to have prepared myself for the dramas that seemed to conspire, pushing children beyond my grasp; and it took more than an iron will to fuel a spirit enabling me to outrun that receding horizon,” he writes.

Photography:

William Atkins