5 Questions On Slam Poetry

By Brittney Dunkins | Photo: Carletta Girma

Elizabeth Acevedo, BA ’10, one of the 2014 National Poetry Slam champions, mixes poetry and performance to explore life and identity as a Dominican woman and first-generation American. She’s also training a new wave of poets as coach of the D.C. Youth Poetry Slam Team, which wowed the audience at TEDxFoggyBottom in April. She spoke with GW Magazine about the art form, its use as a vehicle for social justice and life as a professional poet in this expanded, web version of "5 Questions."

Q: How do you define spoken word and slam?

A: I think people conflate the meanings when really they are just different names for the same thing. They’ll say slam poetry is a separate genre than spoken word because you compete against other poets. I would argue that it’s all just poetry. The poet decides that there is a way they can embody the words on stage, and the energy behind the poem is made more visceral because an audience is watching. Spoken word is just another name for that. It’s poetry that the writer develops with consideration to how it comes across on a stage in three minutes.

Q: How is the process different for performance poetry?

A: The writing is usually pretty similar in the beginning—developing imagery, figurative language, sounds and rhymes. But you can have more subtlety in a poem that you know someone will reread and pull apart to understand all of the pieces. With a performance poem you have to think, “Well, an audience is only going to be able to listen to this once in this moment.” Repetition, pauses and organization help them follow along. And you have to be watchable. Audiences see speakers all the time, from professors to politicians, and they want someone credible on stage. I am always thinking of how hand motions add meaning or punctuation to a word or phrase. Pacing is the same. The way you pace a poem adds to the emotional rise of the message, and you have to build in moments for the audience to breathe.

Q: Issues of sex, class and gender seem central to your work. Why?

A: I grew up in an interesting neighborhood in Harlem: On one end was a really gentrified area with Columbia University, and on the other end was gang violence and crime. I was in the middle. Even at 8 years old, poetry was my way of trying to understand why one side of the street had to deal with these problems that the other side of the street didn’t. Later, a high school teacher who was a mentor to me asked why I never wrote about myself. I realized people couldn’t see who I was in my work. So I made it my mission to express who I am on stage because the personal really is political. I navigate outside issues, but I always try to bring it back to myself, because that is what people relate to.

Elizabeth Acevedo Performs "Hair"

Q: What does the D.C. Youth Slam Team offer students?

A: The D.C. Youth Slam Team is under the umbrella of Split This Rock, an organization that focuses on the intersection of poetry and social justice. Poetry lends itself to being political because it needs a point of view or thesis to work. The students’ lives are charged with political issues from a young age. They are writing about being teenagers in D.C., what it means to be a person of color or to live in a low-income neighborhood. It’s amazing for them because they collaborate, go on stage and tell their stories, and the audience applauds them. It makes them reconsider what they are capable of.

Q: Did you always want to teach poetry?

A: It was a natural path for me. I did Teach for America in Prince George’s County, [Md.], teaching was a part of my duties while completing my MFA at the University of Maryland and I’ve been leading poetry workshops since high school. It’s important to me because even though I was involved in performing arts programs growing up, I never had a teacher of color. I wanted to be that teacher for students coming up. If it hadn’t been for teachers and mentors pushing me, I wouldn’t be here.

Elizabeth Acevedo Performs "A Rat Ode"

More from Elizabeth on her GW Experience and Life as a Professional Poet

Q: How did your GW experience contribute to your growth as a poet?

A: When I got to GW I thought I was going to transfer. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, but poetry wasn’t an option. I remember talking to [Professor of Theatre] Leslie Jacobson, and she suggested I create my own major and offered to be my adviser. It changed everything. I was performing on campus all the time, and I started The Grio, a club for student poets to workshop and hold open mic events. Each year, we organized Café con Leche, a night of performances celebrating Latino culture. I was lucky to do all of these things at GW because they shaped where I am now.

Q: Can this type of poetry be taught?

A: You can’t teach talent, but you can hone in on craft. I try to give students a set of skills: this is the way you enter a poem, this how you free-write, this is how you avoid clichés. Spoken word is really about combining theater and creative writing and figuring out how to make words live on stage. The students have so many stories to tell and we try to help them shape and share those stories. A great poem can come from anybody: a black body, a brown body, a woman, a man, a teenager—anyone.

Q: Did you intend to become a professional poet?

A: I can remember wanting to be a poet in high school after I’d started doing slam poetry competitions, but I also wanted to be an anthropologist. If you think about it, anthropology is the study of man, which is what my work has to do with: history, subcultures and my background as a Dominican and first-generation American. I was drawn to both because they are focused on that initial question of “Who are we?” I think I always wanted to be a working poet but I didn’t think I could do it, because there isn’t a lot of security. It wasn’t until the last couple of years that I really committed and said this is not just what I do, it’s who I am. I am a poet.

Q: What do you aspire to as a professional poet?

A: There is no blueprint or right way to do this. It is incredibly scary. I would love to have a book of poetry published. That means getting up everyday and writing, editing and revising. It means having a great peer group for feedback, and then submitting, crossing your fingers and waiting. Then you just keep writing. It’s so fluid, and with the added layer of performance there is a whole other bracket of things I can do, like performing in new creative spaces. There is always something to reach for, but my focus has always been writing the next poem. I want to craft the next thing that pushes my creativity and surprises me.

Other Summer News

Create Your Own Poetry

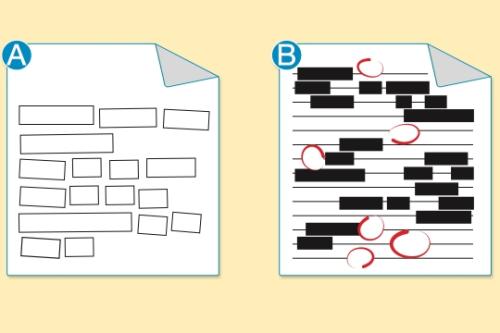

Poetry can be anything. An exhibit at GW's Brady Gallery had visitors create "found poems" by redacting, reordering, refashioning or colorizing a canvas of words made from a few pages of Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Stitch by Stitch

Aspiring costume makers in the Department of Theatre and Dance sketch, stitch and style in GW's costume shop.

Square Dancing With a 3-D Printer

When the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design unveiled its end-of-the-year thesis exhibition this spring, a group of little plastic dragons celebrated the opening with more revelry than anyone in the gallery.

One for the Birds

It was a surprise to find four graduation hoods and a spiffy Stetson top hat in a box described as "cap and gown of Frank Alexander Wetmore."

Alumni News

A pair of politicos reconnect on the air, Eric Cantor appears at GW's Wall Street Symposium and more.

George Welcomes

Laverne Cox, Rick Santorum, five top CEOs and more.

Bookshelves

In Berkshire Beyond Buffett, GW Law professor Lawrence A. Cunningham offers an inside look at Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway, a colossus that manages to feel like a small business.