Revolutionizing the Museum World

Michael Madeja, M.A.T. ’15, starts his morning at the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia checking on the historic Olympia, ensuring that the 19th-century cruiser is still afloat. By lunchtime, he’s leading a hands-on knot-tying workshop for school kids and by the afternoon, he’s brainstorming new ways to make maritime history exciting.

“There’s really no such thing as a typical day,” says Madeja, the museum’s director of education.

This dynamic rhythm—a blend of preservation and innovation—echoes across the museum landscape, where George Washington University alumni are not merely displaying artifacts, but crafting immersive experiences. Many, like Madeja, are graduates of GW’s Museum Education program, which is part of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development and offers an M.A. and a Master of Arts in Teaching with a focus on museum education—preparing professionals to use museums as spaces for community engagement and storytelling.

From the iconic halls of the Met to the covert corridors of the International Spy Museum, these Revolutionaries are redefining the museum experience, proving that behind every display is a tale waiting to be lived, not just observed.

The USS Becuna, a World War II-era submarine, and the USS Olympia, a Spanish-American War-era cruiser, are docked at Penn’s Landing in Philadelphia.

Navigating History at the Independence Seaport Museum

Philadelphia

One summer day at the Philadelphia Zoo, Michael Madeja went beyond simply teaching kids about baby tortoises—he transformed himself into one. Crouched down, with a trash can lid as his makeshift shell, he animatedly detailed how young tortoises develop their protective armor. Hours later, as a group of YMCA campers left the zoo, they spotted him across the street, excitedly shouting tortoise facts and crowning him “the tortoise man.”

That moment stuck with Madeja. “That’s when it clicked—education could be fun, meaningful, and something I wanted to pursue,” he says. “It was this perfect mix of being serious yet silly, rooted in human connection.”

Initially pursuing a pre-med track as a biological anthropology major, Madeja’s summer internship at the Philadelphia Zoo “changed everything.” This realization led him to the museum education program at GW, where he arrived as “the zoo kid.” However, an internship at Ford’s Theatre broadened his perspective.

“History isn’t just about objects—it’s about people. If we can make someone feel what it was like to be a sailor on the Delaware River, then we’ve done our job.”

“I expected to go into natural history, but Ford’s Theatre opened my eyes to working with history in a way I hadn’t considered before,” he explains. “It showed me that being interdisciplinary—combining science, history and hands-on engagement—was possible.”

After graduation, Madeja spent eight years at the American Philosophical Society—the oldest learned society in the U.S., founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743 to promote scholarly research and knowledge in the sciences and humanities—before he was recruited for a leadership role at the Independence Seaport Museum. The opportunity felt like fate for the Philadelphia-area native—his GW application essay had been about the museum.

“They were looking to integrate education into every facet of the museum, from our boat shop to our historic ships to our on-water programs,” he says. “That challenge, plus the ability to build my own team, made it the perfect fit.”

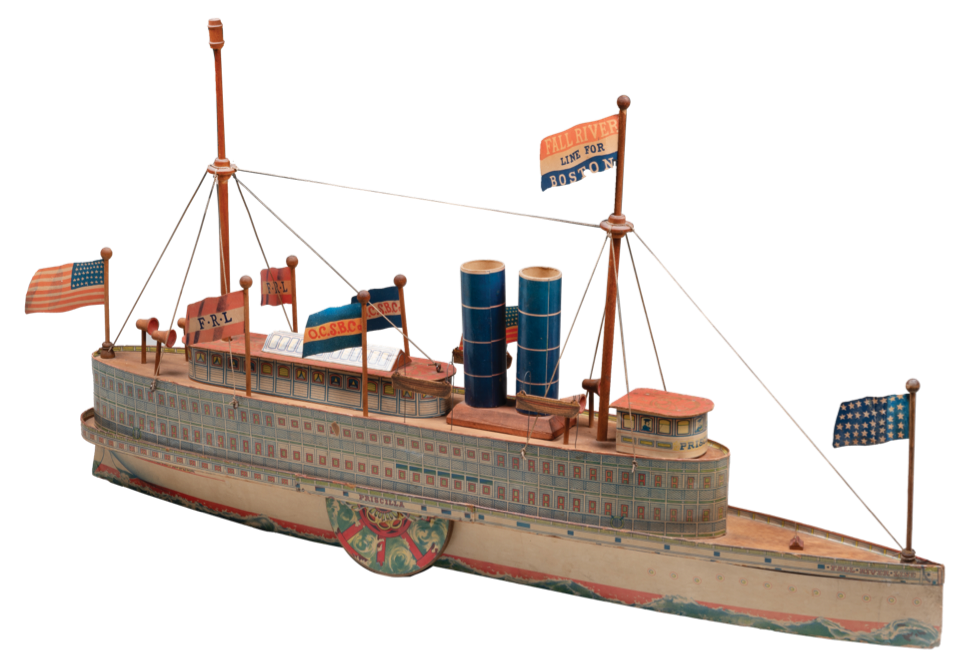

Situated on Penn’s Landing, the Independence Seaport Museum preserves and celebrates the Delaware River’s maritime history, housing one of North America’s most extensive collections of nautical artifacts. Since its official establishment in 1960, the museum has continuously expanded its reach, offering immersive experiences that aim to bring the region’s narrative to life.

Madeja spearheads this endeavor. He embraces the challenge of making maritime history engaging by developing interactive programs for all ages. From teaching students to tie sailors’ knots to incorporating sea shanties into field trips, Madeja ensures that every visitor leaves the museum with a personal connection to the past.

Left: Students learn to tie knots during a workshop at the Independence Seaport Museum. Above: The toy steamer Priscilla, produced around 1896 by the R. Bliss Manufacturing Company.

“History isn’t just about objects—it’s about people,” he explains. “If we can make someone feel what it was like to be a sailor on the Delaware River, then we’ve done our job.”

Madeja forges connections through storytelling, placing community at the heart of his museum education. His most resonant project: collaborating with Philadelphia's Filipino-American community to reclaim the legacy of the Olympia, which played a key role in the U.S. colonization of the Philippines.

In 1898, the cruiser served as Commodore George Dewey’s flagship during the Battle of Manila Bay, where the U.S. defeated the Spanish fleet. This victory marked the start of American rule in the Philippines, transitioning the country from Spanish to U.S. colonial control. The Olympia thus symbolizes the beginning of a complex and often painful chapter in Philippine history—one of imperialism, resistance and cultural upheaval.

“My dad is Filipino-American, and he worked at the Navy Yard, so this project was personal for me,” he says. “At the exhibit opening, seeing Filipino families on board, eating, celebrating and discussing history—it was powerful. It demonstrated that museums can be places of both joy and deep reflection.”

For Madeja, this intersection of history, social consciousness and local identity defines the Independence Seaport Museum. He cites the “pineapple protest,” when longshoremen tossed pineapples into the Delaware River to protest Del Monte’s exploitation of workers and land in the Philippines, as a prime example.

“That event reminds me of how Philadelphia’s revolutionary spirit is uniquely blended with its inherent quirks,” he reflects, emphasizing the city’s passion intertwined with its penchant for the absurd—much like Madeja himself.

Photography: Courtesy of the Independence Seaport Museum

Plan your visit to the Independence Seaport Museum today at phillyseaport.org

The International Spy Museum and a World War I pigeon camera.

Uncovering Secrets at the International Spy Museum

Washington, D.C.

The rich, sweet scent of chocolate hangs heavy in the air, while the resonant sound of a trolley car rolls through the cobblestone streets. A teenage Liz Mueller, M.A.T. ’20, a self-proclaimed “theater kid,” stands at the front of the trolley, putting on a musical history tour of Hershey, Pa. At the time, she saw her gig at Hershey Trolley Works as just another performance, but in retrospect, it was her first true educational role.

Mueller’s interest in education deepened during her undergraduate years at Cornell University, where she studied environmental science. A communications course required her to develop and teach an hour-long lesson on an environmental topic at local schools. That experience, combined with a guest lecture from a museum professional at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, opened her eyes to museum education.

“I had no idea museum studies was an actual career path until that moment,” she says. “It was the perfect way to combine my love of science, performance and teaching.”

GW’s museum education program was a natural next step, introducing her to an invaluable professional network. “The number of GW connections in this field is wild,” she says. A perfect example emerged during the interview when Madeja’s name came up. “Oh, he was like a mentor to me during my time at GW!” Mueller remarked.

And like Madeja, Mueller’s career trajectory initially pointed toward zoos and aquariums—her internships included a Montessori classroom field trip to the National Museum of Natural History and a position with Friends of the National Zoo—but a part-time job leading birthday parties at the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., took her in an unexpected direction.

“I thought I’d only be there for a short time, but when the pandemic hit, I was lucky—the Spy Museum had already been running virtual programming for years, so I was able to continue teaching workshops remotely,” she explains. “Eventually, they opened up a full-time position, and I realized I didn’t want to leave.”

The International Spy Museum is the only public museum in the United States dedicated to international espionage. It features a vast collection of spy gadgets, weapons and artifacts, and explores the history of espionage from ancient times to the present day. The museum also highlights the stories of famous spies and their missions, offering interactive exhibits and simulations that allow visitors to experience the world of espionage firsthand.

“I thought I’d only be there for a short time, but when the pandemic hit, I was lucky—the Spy Museum had already been running virtual programming for years, so I was able to continue teaching workshops remotely,” she explains. “Eventually, they opened up a full-time position, and I realized I didn’t want to leave.”

As a museum educator, Mueller builds upon this immersive experience. Her days are packed with interactive programs, school workshops and special events. She’s the point person for educators bringing students to the museum, managing logistics and content development. In 2023 alone, she led over 200 workshops covering topics from the Revolutionary War to the Cuban Missile Crisis—both in person and virtually.

She also helps organize large-scale events like Spy Fest, where intelligence agencies set up demonstrations and showcase real espionage technology.

But Mueller’s enthusiasm extends beyond event planning; it’s rooted in the fascinating artifacts and stories she shares daily. One of her favorite pieces is a World War I pigeon camera—an early precursor to drone surveillance.

“They didn’t have modern technology for aerial reconnaissance, so they strapped tiny cameras to pigeons and let them fly over enemy territory,” she says. “You can actually see parts of their wings in the photos.”

The museum stands out not just for its gadgets and technology but also for its focus on human stories, particularly those that are often overlooked in traditional history. A notable example is Virginia Hall, a World War II spy who used a wooden leg named “Cuthbert.” Hall’s unconventional path to espionage resonates deeply with Mueller, who first researched her for a seventh-grade history project.

“She wasn’t who you’d picture as a spy—she was underestimated at every turn. And yet, she was one of the most effective intelligence operatives of her time,” Mueller says. “In a way, that mirrors what we do at the museum—we challenge expectations and uncover the hidden stories behind history.”

Photography: Courtesy of the International Spy Museum

Plan your visit to the International Spy Museum today at spymuseum.org

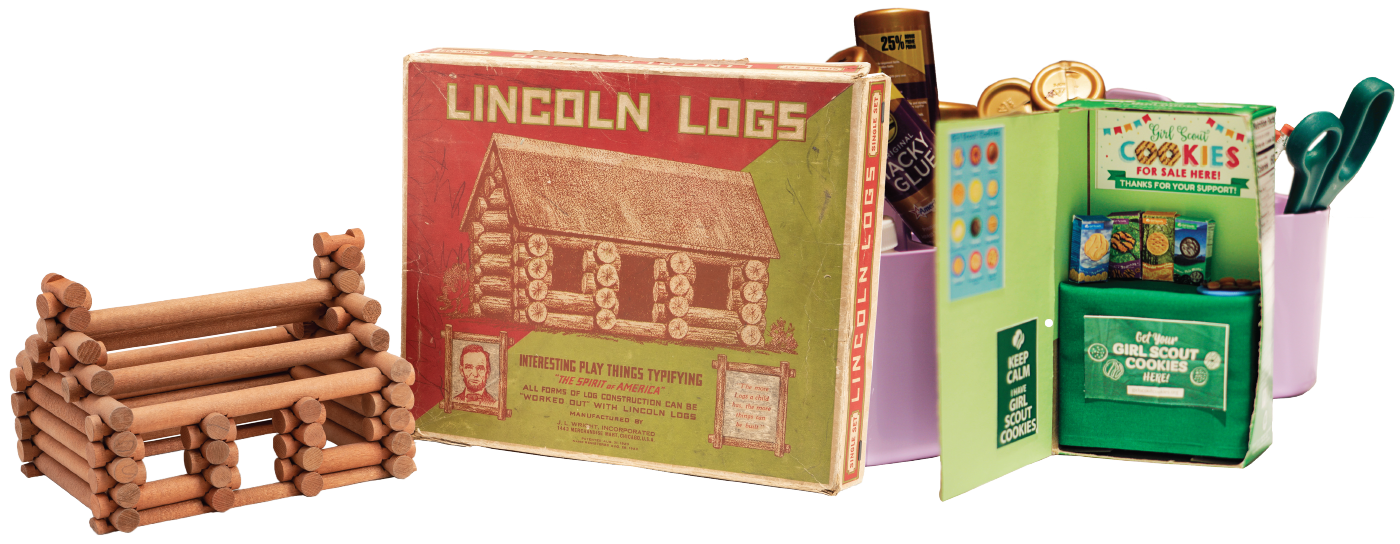

Left: Frank Lloyd Wright's son, John, invented Lincoln Logs in 1916. Right: A miniature Girl Scout cookie booth.

Cultivating Joy at the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures

Kansas City, Mo.

The green roofs, the red chimneys, the yellow windows—Faith Ordonio, M.A.T. ’20, can still picture the Lincoln Logs scattered across her childhood floor. For hours, she’d lose herself in constructing elaborate cabins and sprawling towns, transforming simple wooden beams into entire worlds. Back then, toys were just a source of joy and imagination. Now, they’re the centerpiece of her career.

A high school aptitude test first sparked Ordonio’s interest in museums, suggesting a future as a curator. Inspired by this idea, she studied history and geography at the University of Missouri.

However, an internship at the State Historical Society of Missouri helped her discover where she truly belonged—not in curation, but education. While helping prepare for the Missouri Bicentennial, she saw firsthand the impact of making history come alive.

“It was really cool prepping for that and seeing the kids get excited for the Bicentennial of Missouri statehood coming up,” she recalls.

This experience ignited her passion for museum education and ultimately led her to GW, where she found a community that shared her vision.

“I felt like I found ‘my people’—people who love museums as much as I do and want to make them more inviting and engaging for visitors.”

“I felt like I found ‘my people’—people who love museums as much as I do and want to make them more inviting and engaging for visitors.”

Then, just weeks before Ordonio’s graduation, the coronavirus pandemic hit.

“It was a great time to be in a lot of debt and look for a job that didn’t exist,” she quips, highlighting the challenging circumstances she faced upon entering the job market.

After a brief stint as a substitute teacher in Missouri, Ordonio spent three years as a school programs educator in upstate New York (a time she wryly refers to as “enduring three Adirondack winters”). This experience, she notes, provided her with valuable classroom teaching experience, skills that ultimately helped her secure her position at the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Kansas City, Mo.

The National Museum of Toys and Miniatures, founded in 1982 by Barbara Hall Marshall and Mary Harris Francis, houses a collection of nearly 100,000 objects. It features both toys and fine-scale miniatures, two distinct categories, though both are typically small in size.

As the museum’s K-12 and family programs educator, Ordonio orchestrates learning experiences that make history tangible and exciting for young visitors. Her days are a mix of high-energy sessions with students and careful planning, ensuring every activity fosters both learning and wonder.

One initiative Ordonio is especially proud of is helping local Girl Scouts earn their Miniaturist Badge. The badge was originally created as a “make-your-own” badge by a Girl Scout troop in the Chesapeake Bay area but hadn’t been implemented widely outside that region. When Ordonio, a lifelong Girl Scout, learned about the badge, she recognized an opportunity.

“I thought, ‘This is perfect for Kansas City—we're literally the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures!’” she recalls.

So she designed a workshop for the girls to create their own miniature cookie booths, crafted from real cookie boxes.

“There was a ton of prep involved—we spent days cutting out miniature cookie boxes, making tiny cookies out of clay and using X-Acto knives to pre-cut doors so they could complete their booths in just two hours,” she explains. “But seeing their pride in their work made it all worth it.”

A few weeks later, one of the Girl Scouts from the program recognized Ordonio at the museum and excitedly introduced her to her grandmother. That “full-circle moment” highlighted the impact of Ordonio’s work—not only teaching children about history but also creating positive memories.

“My favorite thing is when kids walk out of the museum saying, ‘This was the best day ever! I want to come here again!’”

Lincoln Logs, 1928, J.L. Wright, Inc., 1928, United States. Photo by The National Museum of Toys and Miniatures.

Plan your visit to the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures today at toyandminiaturemuseum.org

New York City

Picture an artist, scrolling through Instagram, discovering a vibrant community connecting them to museums and art lovers across the globe. That’s the vision Karen Vidangos, M.A. ’17, is helping to realize. From recognizing the need for a centralized space for Latinx artists to shaping the social media strategy at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vidangos is driven by a powerful goal: to break down barriers and amplify underrepresented voices in the art world.

Like many of her peers, Vidangos’ path to museum work wasn’t straightforward. As an undergraduate studying art history, she knew she loved museums but wasn’t sure where she fit within them. It was a professor who recognized her potential and encouraged her to pursue GW’s museum studies program—a decision that proved pivotal.

“It really shaped how I think about museums and my role in them,” she says.

After earning her master’s degree, Vidangos spent nearly a decade building expertise in digital engagement and audience development before landing her current position as the Met’s senior manager of social media. “Now I realize this is what I have been working towards,” she says. “This is the culmination of everything I have tried to build in the museum field.”

Founded in 1870, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is one of the world’s largest and most prestigious museums, with a collection spanning over 5,000 years of art. Its vast galleries attract millions of visitors each year, but Vidangos is helping the museum reach even more people—far beyond its physical walls.

“Social media has been incredible for museums to share their collections with a much wider audience—some who may never be able to step foot in New York City and experience the Met,” she says.

At the Met, Vidangos takes a big-picture approach to social media, crafting digital storytelling strategies that reflect the museum’s diverse audience. Collaborating across departments, she ensures that exhibitions and collections resonate with both national and international audiences.

“I think about our audience and how we want to engage them—whether it’s through exhibition previews, behind-the-scenes content or interactive campaigns that invite the public to share their own perspectives,” she explains. Social media, in her view, isn’t just a marketing tool; it’s a way to democratize access to art and amplify underrepresented voices.

Historically, museums have been exclusive spaces, and Vidangos is determined to change that. By fostering online conversations and highlighting diverse narratives, she’s ensuring the Met isn’t just preserving history—it’s evolving to be more inclusive.

“Social media allows for multiple perspectives,” she says. “It doesn’t just come from a curatorial level. Now, people can engage with our collection on their own terms, bringing their own experiences and interpretations to the conversation.”

Beyond her role at the Met, Vidangos has taken personal action to address the lack of representation in the art world. She founded the Latinx Art Collective, a digital platform dedicated to increasing visibility for Latinx artists. Through virtual exhibitions, artist talks and social media campaigns, the collective has become a vital hub for connection, engagement and advocacy.

“I realized there was no centralized space for Latinx artists,” she says. “So I created one.”

Navigating the museum world as a Latinx professional hasn’t always been easy. Vidangos has encountered the industry’s inherent elitism and moments of feeling like an outsider. “You feel like you’re stepping into a world where you do not belong, where you are marginalized or feel marginalized,” she admits. But instead of retreating, she has leaned into her identity, using it as a source of strength. “I have been unapologetic about who I am and what I stand for,” she says. “I want to make changes. I want to elevate and amplify Black and Brown voices.”

Her work is already making an impact. She’s seen museums—including the Met—engage more deeply with local communities and independent creators. She champions social media as a bridge between these institutions and the dynamic cultural spaces where art is discussed, created and redefined. “Museums can no longer exist as isolated entities,” she says. “We have to meet people where they are.”

And as for where she is, Vidangos hopes she’s found a place to stay for the long haul.

“I didn’t think that already I would find an institution that I truly felt at home with,” she says with a smile, “but I think the Met might be that place.”

Photo by Bridgit Beyer, courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Plan your visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art today at metmuseum.org

Visitors explore "Terracotta Army: Legacy of the First Emperor of China" [above] and "Frida: Beyond the Myth".

Leading a Vision at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Richmond, Va.

As a boy, Alex Nyerges, B.A. ’79, M.A. ’82, spent countless weekends riding the bus to the Rochester Museum & Science Center, captivated by the magic of its vast collections. Little did he know that those childhood immersions—among ancient artifacts and artistic wonders—were laying the foundation for his future.

But the museum offered only half of his artistic education. The other half unfolded at home, where creativity flourished. His mother, a tuberculosis survivor, painted daily, transforming their house into a living gallery, while his father, an immigrant factory worker from Hungary, meticulously crafted frames, proudly displaying his wife’s work.

“My mom was just enamored with art,” Nyerges recalls. “She spent the last 30 years of her life painting every day, and my dad made the frames and cut the mats for her.”

Surrounded by both institutional collections and intimate, hands-on artistry, Nyerges developed a deep appreciation for the arts. Yet, his first love wasn’t painting—it was archeology. He arrived at GW as an archaeology major, envisioning a career unearthing the past. But that dream changed after a summer dig in eastern Colorado.

“I decided I hated dirt and wanted to work inside a museum, not out in the field,” he recounts with a laugh. “I also decided I hated archeology; I was more interested in the objects themselves.”

That revelation led him to GW’s museum studies program, where he set his sights on museum leadership. Fresh out of school, he landed his first directorship at Florida's DeLand Museum of Art.

“I was it—the curator, PR director, development officer, even the guy helping with maintenance,” he says. “It was the best learning experience I could have asked for.”

“Our goal is simple: to make art accessible to everyone. Because at the end of the day, art belongs to all of us.”

Nyerges thrived, gaining hands-on expertise in every facet of museum operations. From DeLand, he moved to the Mississippi Museum of Art, where he pioneered the nation’s first statewide branch museum system, bringing fine art to underserved communities. He then spent 14 years at the Dayton Art Institute, expanding programming, fundraising and community engagement.

His success in Dayton caught the attention of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA), which recruited him in 2006 to lead the Richmond-based institution into a new era. Today, as director and CEO, Nyerges oversees a $60 million budget, a staff of 700 and a museum that welcomes more than two million visitors annually. Under his leadership, VMFA is undergoing a historic expansion, with a new wing set to open in 2028—poised to make it one of the nation’s largest art museums.

“Our goal is simple: to make art accessible to everyone,” says Nyerges, who was named a GW Monumental Alumnus in 2021. “We’re the only major U.S. art museum with free general admission 365 days a year, and we’re committed to reaching every corner of Virginia.”

One of VMFA’s most impactful initiatives is the Artmobile, a climate-controlled traveling museum that brings exhibitions to communities statewide. Last year alone, the program reached 375,000 visitors, reinforcing Nyerges’ mission to break down barriers to art.

Beyond expansion and accessibility, he has strengthened VMFA’s collections. Among his proudest achievements is acquiring the world’s largest collection of traditional Tanzanian artwork, surpassing even Tanzania’s national museum. Another deeply personal milestone was curating an exhibition on Hungarian-American photographers, inspired by his father’s passion for photography.

“I worked on that exhibition for over a decade,” he says. “Seeing it come to life at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, then at VMFA, and soon at the George Eastman Museum—it’s been a dream come true.”

With Nyerges at the helm, VMFA has embraced both tradition and innovation, cementing its role as a cultural hub for generations to come. His vision extends beyond exhibitions and acquisitions—he sees museums as essential community spaces that educate, inspire and bring people together.

“In 30 years, I see VMFA reaching even more Virginians, making art a part of their everyday lives,” he says. “Because at the end of the day, art belongs to all of us.”

Photos by David Stover, Sandra Sellars and Jay Paul. Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Plan your visit to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts today at vmfa.museum