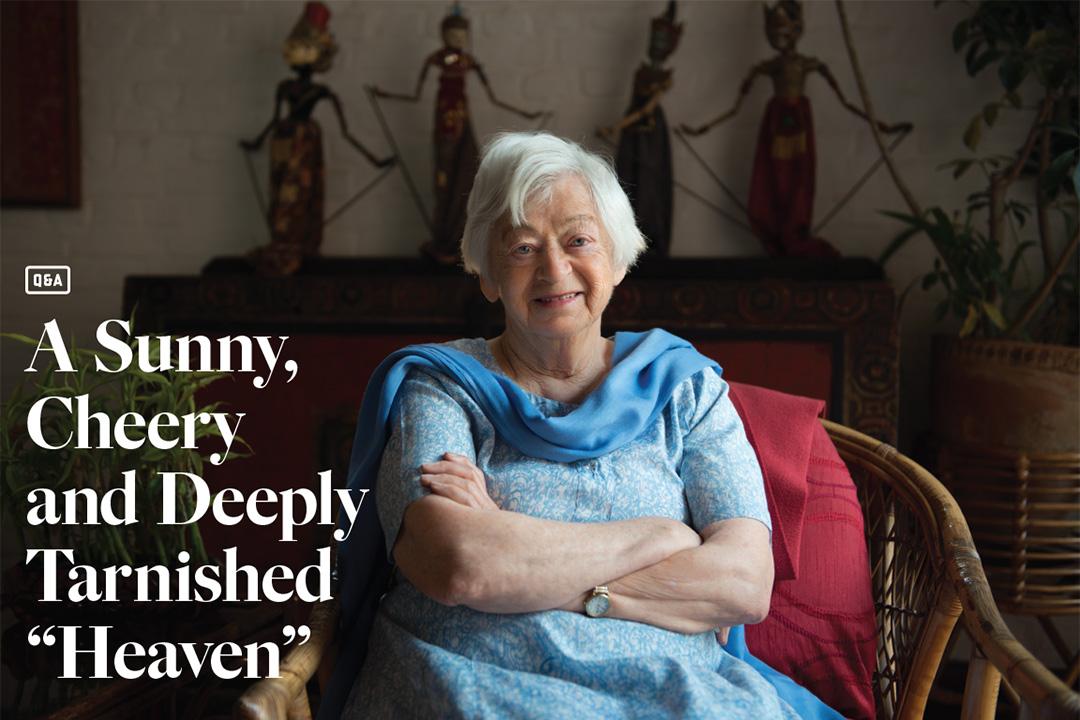

Q&A: A Sunny, Cheery and Deeply Tarnished “Heaven”

(Susan Hale Thomas)

Thirty years ago, an alumna found Nepal to be a place where the people smile “in the face of … terrible things,” and since has dedicated herself to lightening their load.

By Matthew Stoss

Olga Murray, BL ’54, believes that people—with “a few psychotic exceptions”—are intrinsically good. The 91-year-old former research attorney for the California Supreme Court has always believed this. And today, because of Nepal, despite its poverty and pollution, she’s never believed in the goodness of people more.

“The people are so wonderful, so welcoming, so cheerful in the face of these terrible things that you just want to stay,” Ms. Murray says by phone from her home in Sausalito, Calif., where, typically, each year for the past three decades she has spent just five months a year and the rest in Nepal.

In 1990, Ms. Murray founded the Nepal Youth Foundation, an organization that spends $2 million a year providing education and health care for impoverished and abused Nepali children. Ms. Murray talked with GW Magazine about Nepal, her work and what she’s learned.

On Olga Murray ...

GW Magazine: Why Nepal?

Olga Murray: Some women fall in love with men. I fall in love with countries. I was crazy about Greece and kept going back year after year, and I thought, you know, I really ought to go to Asia some place instead of going back to Europe all the time. And I decided I would go to India for six weeks [in 1984]. And then I thought, oh, there’s little country next door I heard about, and they say the trekking’s good. I’ll just take a couple weeks of my trip to India and go trekking [in Nepal], just like that. … It was like heaven. The sun was shining. People were laughing. It was just such a joyful environment. They were holding hands in the street and laughing and talking and smiling at you, and just the minute I got off the plane, I felt comfortable and happy.

GW: Why did you start the Nepal Youth Foundation?

OM: Most kids didn’t go to school at that time, and all of them wanted to go school.

GW: Another major part of the NYF is freeing girls from indentured servitude—a system known as “kamlari,” which was banned by the Nepali government in 2014 after the NYF started a formal campaign against it in 2000. Has there been resistance to the organization’s efforts?

OM: Our staff has had threats in [the rural] areas from people who are doing the selling of the girls and from employers who wouldn’t release the girls—even some of the girls were under threat if they left. But, you know, they’re just brave people and we did everything legally. … We got the community on our side, and once that happened, then these people they could only make idle threats. But it’s not like the Mafia. These were not organized people.

GW: You’ve seen a lot of the worst of humanity. What is it that makes you believe in the basic goodness of people?

OM: Their capacity to raise themselves up. It’s something that I’ve seen literally thousands of times there that really made me hopeful about people.

GW: Do you see that in the NYF?

OM: We’ve had 50,000 kids through our program, and, of course, I don’t know the vast majority of them. But [of] the ones I know—which are a few thousand—I can literally count on the fingers of one hand the kids I would consider failures. One hand.

GW: What’s your role today in the Nepal Youth Foundation?

OM: I know the girls and they know what I’m doing, but I’m not the person who stands up there and says, “This is terrible and an inhumane practice.” We have staff who live locally, completely integrated with the community, and we mobilize the community to fight for our causes, and that’s really the secret. So it isn’t me going in and saying, “Here I am, this American, and I know what you should do.” No not at all.

"We’ve had 50,000 kids through our program, and of course, I don’t know the vast majority of them. But [of] the ones I know—which are a few thousand—I can literally count on the fingers of one hand the kids I would consider failures. One hand.”

GW: The United States has a reputation for being, well, a bit lavish. Has your time in Nepal changed how you view America?

OM: When I first come back [from a trip to Nepal] and people complain about the most ridiculous things, I think to myself, “Grow up. You know you are so lucky. You just don’t know the place you hold in this world.” And I think back to the [Nepali] people who have really serious complaints and [they] smile a lot and are generous, and I don’t have much patience with the not-very-serious complaints in this country. I feel that people don’t appreciate what they have and they’re not as happy as they should be, given their circumstances. … When I think of what things cost here, I go crazy. It just drives me nuts. I just think what I can do with this in Nepal, I can actually save lives for a few dollars.

GW: One U.S. dollar is equal to a little more than 100 Nepali rupees, and in Nepal, $20 can feed a family of four for a week.

OM: I mean, you can’t get an aspirin in an American hospital for that. … I know what it’s like to be a millionaire, honestly. I know that in Nepal, if anybody comes to me and says they “need an education,” “I need an operation,” “I need a place to live,” I could do it all. I can’t do it for everybody, but I could do it for anybody that I encountered who needed that.

GW: Have you done that?

OM: Yes, we can save a malnourished child’s life for $270 at the 16 little hospitals we have established for that purpose, and we can send a village child to school for $100. The level of poverty and the way people do this backbreaking physical work—it’s very upsetting. And I ride through Kathmandu in my air-conditioned car and my heart is so sad all of the time, and if I couldn’t do anything, I couldn’t stand it.