Looking Back at 1821

Looking Back at 1821

The year Columbian College was founded Washington, D.C., was a watery, underwhelming capital city and the United States was striking an uneasy—and ultimately untenable—compromise on slavery. It was also a year of revolution that altered the world landscape as much of Latin America waged independence wars and the Greeks rebelled against the Ottoman Empire. We examine the many landmark events that continue to affect the world we live in 200 years later.

By Menachem Wecker, M.A. ’09

In 1825, German Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach recorded streets outnumbered District of Columbia houses, dissatisfying already low expectations for the city. Washington was built for 1 million residents but had just 13,000, he wrote. “To be the capitol of such a large country, Washington lies much too near the sea.”

The prior year, President James Monroe and Marquis de Lafayette joined celebrants at the first Commencement of Columbian College, founded in 1821 by congressional charter. The school would change its name to George Washington University more than 80 years hence. Whether streets then outnumbered houses literally—just a few years after the British burnt government buildings, including the Capitol and the president’s home—Washington looked very different then.

Starting in 1815, the portion of Constitution Avenue hugging the National Mall on the north was part of Washington City Canal, connected to the Potomac River, then much wider between present-day Arlington National Cemetery and the district. Several decades later, the river would be dredged and reclaimed as land, now holding the Lincoln Memorial and Tidal Basin.

In realizing George Washington’s wish for a national university, Columbian College became the district’s second higher-education institution and presented (initially) a Baptist contrast to Jesuit-affiliated Georgetown University, founded in 1789.

Not only was the District on the cusp of change in 1821 but so was the fledgling country of the United States and much of the world. In more than a dozen interviews, GW faculty and alumni with expertise in early 19th-century world history reflected on some of the major changes the year of Columbian College’s creation and the ways 1821 seeds continue to impact the world in 2021 as GW celebrates its bicentennial.

The West’s Strained Gateway

On Aug. 10, 1821, Missouri became the Union’s 24th and then-westernmost state as part of an

agreement—the “Missouri Compromise”—that saw Maine enter the prior year as a free state and Missouri as a slave one. It would be 15 years before the 25th state, Arkansas, was admitted.

The War of 1812 had gone poorly for the nation and particularly Washington, evidenced by the ashes of great buildings. Because it ended a disastrous war, the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814 felt like a victory for the nation, although it “basically decided nothing,” says Denver Brunsman, associate professor of history. A financial panic—“recession” or “depression” in today’s parlance—broke out in 1819, and bitter negotiations led up to the 1820 compromise, which politicized slavery in then-unparalleled manner.

“Massachusetts did something pretty unprecedented by that point in U.S. history,” Brunsman says. “It just lopped off its northern counties to create a new state, Maine, to balance the slave and free states.”

Compromise forged, a sense of relief ensued, but there were also the first predictions the nation was on the path to civil war. Overall, the 1820s were devastating for African Americans and indigenous peoples, says Richard Boles, Ph.D. ’13, assistant professor of history at Oklahoma State University.

Slavery extended westward and southward, and the total number of enslaved people rose. Federal policies supported taking Native land, culminating in the 1830 Indian Removal Act. Although Northern states gradually sunset slavery starting in the 1780s, anti-Black riots occurred in Northern cities in the 1820s and 1830s, and Northern schools, public transportation, work and neighborhoods remained segregated, according to Boles.

His research shows Northern Protestant churches were interracial yet segregated in the 18th century, but largely ceased being the former by the 1840s. “When Black participation in predominantly white churches swiftly declined between 1820 and 1840, this decline affected race relations in the rest of Northern society,” Boles says.

After two centuries, oppression of African Americans and Native Americans continues. “Until we can collectively and honestly address the history of slavery, segregation and land thefts, structural inequalities will persist in our society along racial lines,” Boles says.

Back in 1821, the young country had just emerged from financial crisis, brought on when Europe, having recovered from the War of 1812, ceased requiring U.S. food exports. That led to more U.S. land speculation. In 1820, President Monroe, “who was more popular than we give him credit for today,” won reelection unopposed, Brunsman says. Monroe attended the 1824 Columbian College graduation. “All those things come together, and there was some hope for brighter days,” Brunsman says, noting 1821 was part of the “Era of Good Feelings.”

“There was a sense of optimism. The country was growing. There’s a sense of momentum,” he says. “Historians describe something called the ‘market revolution,’ which began to take hold right around that time. This is a process that describes how the United States grew into a national capitalistic economy rather than just a regional or local economy.”

Washington’s Unrequited Admirer

When a mob stormed the Bastille in 1789 in the early French Revolution days, many Americans

were excited by the prospect of a French republic. That diminished when terror and global war began in 1793, though Democratic Republicans and Jeffersonians stateside continued to support the revolution. Federalists opposed France and supported Britain.

“Most Americans became disappointed in the French Revolution and what it became under Napoleon, but I think if they had to choose their enemy, they despised Britain more than France,” Brunsman says. “That was one of the fault lines of American politics.”

In 1821, Napoleon—who had a “love-hate” relationship with the United States for his role in the French terror and global war—died (apparently of stomach cancer) in exile on St. Helena, an island some 1,200 miles off Africa’s southwest coast. That closed the book on a 51-year life that Americans admired, feared and despised, according to Brunsman.

Napoleon was drawn to George Washington, for whom he instituted a mourning period in France after Washington's death in 1799. It’s unclear what Washington thought of the emperor, but Brunsman figures he was no fan. Washington’s all-but-adopted son, Lafayette, sent him a key to the Bastille, which Washington displayed proudly in the president’s executive residence and then at Mount Vernon, where it remains on display today. “It’s one of the only objects that’s never left Mount Vernon,” Brunsman says.

Napoleon admitted he was no Washington. “After he was exiled to the island of Elba after being defeated by the British, he wrote to a correspondent, ‘They wanted me to be another Washington,’” Brunsman says. “It’s kind of fitting in a way that Napoleon’s passing is the same year that Columbian College, which would become George Washington University, was founded. Almost like a passing of the torch or changing of era.”

In the college’s infancy, the nation began growing in ambition, and the Monroe Doctrine warned European countries against interfering in the Western Hemisphere. That warning was “kind of anti-Napoleon or anti-imperial,” Brunsman says. “I see the founding of GW in this period, in which the United States really began to take off, not as a world power yet, but a growing power.”

Fearing the Square and Compasses

In the 1820s, Americans became big believers in conspiracy theories, particularly that Freemasons, a then-secret fraternal order tracing its origins back to medieval stone masons and cathedral builders, were trying to take over the government, says Tyler Anbinder, emeritus professor of history. An anti-Masonic political party emerged at the time and became significant in New York, among other states. “Americans were already showing their willingness to believe outlandish conspiracy theories,” Anbinder says.

The belief in a Masonic conspiracy reflected the success of the universal suffrage movement, according to Anbinder. As more people secured voting rights irrespective of property ownership, conspiracy subscribers questioned whether their votes mattered given their belief that Masons were freezing common men out of political power. (Also excluded? Black people, Native Americans and women, who couldn’t vote for another century or more.)

In ensuing years, conspiracy theories metastasized to target Catholics (alleging papal invasion plans) and to followers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons). This parallels the way George Soros today is seen by some as “the new idea of a ‘foreign threat,’” Anbinder says. “The Masons have been displaced by other groups in the popular imagination.”

A lot has changed in 200 years. Catholics, then seen as “the wrong kind of conservative,” are a Supreme Court majority today and hold the House speakership, presidency and more than a quarter of congressional seats. But there is some reason to pine for certain realities of 1821, when there was little xenophobia and little domestic anti-Muslim animosity.

After the War of 1812, the biggest national concern was a country the Louisiana Purchase expanded considerably in 1803. “Americans were thinking: We’ve got to fill up all that space so that we can control it before the British, French or Spanish come and take it from us,” Anbinder says. “Immigrants were welcome, because they would fill up that space and make it harder for some adversary to take it back.”

Most immigrants then were English Protestants, and it was only when Irish Catholics began immigrating in larger numbers that many Protestant Americans saw immigration unfavorably. With few Muslims living in America in 1821, there was little anti-Muslim sentiment, although after decades of American crews being captured and ransomed by pirates in present-day Libya and Algeria, there was a lot of hateful sentiment toward North African nations during the Barbary Wars (1801 to 1805).

“It was very different than today. People didn’t talk about religion per se and say: Well, here are the parts of the religion we don’t like. It was more that Muslims were thrown in with a lot of others and seen as ‘heathenish,’” Anbinder says.

Coming of Artistic Age

A particularly dramatic difference between the United States today and in 1821 lies in the visual arts, says Alex Nyerges, B.A. ’79, M.A. (museum studies) ’82, director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA). In 1821, the nation was “an artistic desert other than the major Eastern seaboard cities, such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston and Savannah,” he says.

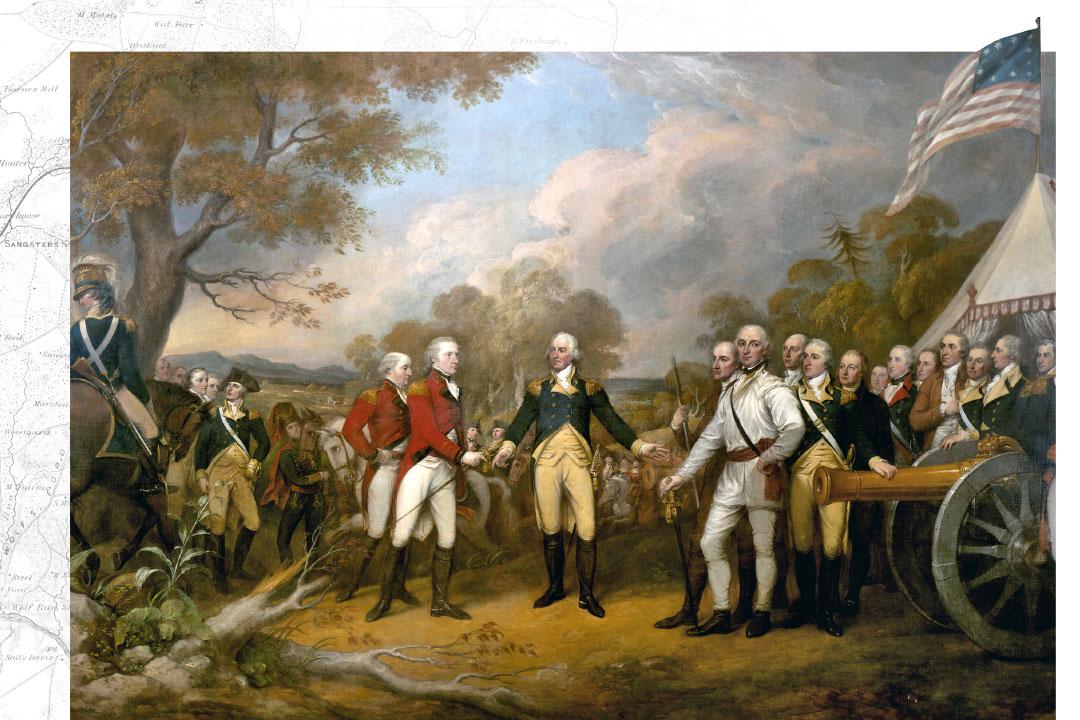

The VMFA wouldn’t open until 1936, amid the Great Depression, but its collection contains several 1821 treasures, such as an imagined Italianate landscape by Joshua Shaw, one of the country’s first landscape painters, and a mounted jockey, which accomplished artist and equestrian Théodore Géricault painted. George Catlin, whose American Indian depictions abound at the Smithsonian, become a painter in 1821, the same year designer Louis Vuitton was born. Esteemed British artist John Constable painted his iconic “Hay Wain” (at London’s National Gallery) in 1821, when stateside, John Trumbull painted “Surrender of General Burgoyne,” which remains in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

Washington and Richmond were relatively small and backward then, and American art was derivative of European prototypes. The nation’s first true art museum, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn., was yet 21 years away from Columbian College’s founding. Today, thousands of U.S. art museums can be found. “It makes the establishment of what will become one of America’s great universities in the new District of Columbia all the more fascinating,” Nyerges says. “It was ambitious and forward thinking.”

Conversely, U.S. decorative arts were innovative in 1821, particularly fine furniture, porcelains and silver, largely for domestic use. Tastes had shifted by 1821 from lavish rococo furniture of Thomas Chippendale and silver of Paul de Lamerie to “more austere, simpler lines of the Hepplewhite and Regency styles,” Nyerges says. “Gone was the ornate.” An echo emerges in Apple’s sleekness, which responded in the 1990s to approaches of the Italian postmodern Memphis design movement. Nyerges doesn’t see decorative ornateness, such as the “brown furniture” of the 18th century, making a comeback any time soon. “People can’t give it away, which is very sad,” he says.

An Enduring ‘Underground’ Prophet

Reading “Crime and Punishment” in high school, Michele Levy, B.A. ’70, found herself entering a distant yet familiar world. The professor emerita at North Carolina A&T State University wrote her dissertation on Fyodor Dostoyevsky and D. H. Lawrence.

“My elevator pitch would be: Read Dostoevsky, and change your life,” she says. “See how modernity deconstructs traditional society, how greed and power-hungry leaders, together with their minions, ravage their citizens. Journey deep inside the soul, where conflicting passions battle and existential questions—the meaning of life and death; the nature of truth, love, faith and God; the value and cost of freedom—acquire flesh.”

The Moscow into which Dostoevsky was born in 1821 had recovered from Napoleon’s failed 1812 invasion, Levy says. Dostoevsky grew up interacting with patients at the poor hospital where his father was a doctor. His parents encouraged his education, both religious and secular. Dostoevsky left Moscow at 15 for engineering school in St. Petersburg, where he would set future novels. It is “the most theoretical and intentional city,” he wrote in “Notes from Underground.”

Dostoevsky’s life continues to offer a “cautionary tale” 200 years after his birth. He joined a “Western-influenced underground group” and was arrested, jailed and put through a mock execution. “Encountering only condescension and materialism in the West, he came to view it as his people’s enemy,” Levy says. “Many have followed such a path to terrorism, autocracy and theocracy. Many continue to do so.”

Dostoevsky’s writings influenced Nietzsche, Freud, Sartre, Camus, Faulkner, Hemingway, Ellison, Hesse and Mann, among many others. “Dostoevsky is a prophet who continues to fuel my work, both scholarship and fiction,” Levy says. (Her new novel is titled “Anna’s Dance: A Balkan Odyssey.”) “Through generations of readers, Dostoevsky has helped shape the 21st century. His 19th-century seeds continue to bear a rich harvest as they influence those who shape our world.”

It’s All Greek

Two of the most famous images of the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire,

which began in 1821, take artistic license.

French philhellenic painter Eugène Delacroix’s “Greece Expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi” (1826) personifies Greece as a woman mourning fallen compatriots as an Ottoman soldier claims territory behind. “The work promoted the Greek cause—which was variously depicted by Greeks and philhellenes alike as a struggle between Christianity and Islam, East and West, civilization and tyranny, despotism and freedom—to Western audiences,” says Dean Kostantaras, Ph.D. ’05, associate professor of history at Northwestern State University.

The other painting, by Vryzakis Theodoros at Athens’ National Gallery dated 1865, depicts metropolitan (priest) Germanos of Patras blessing the revolutionary flag—a blue cross on a white background—at Agia Lavra monastery. The famous flag raising on that day in 1821 and proclamation of revolution is celebrated to this day as Greece’s independence day.

“It remains one of those ‘events’ from the revolution that is a matter of myth for some historians, and yet is a mainstay of popular depictions, ‘memories’ and public celebrations of the conflict,” says Kostantaras, who hasn’t found many references to the “event” in primary sources from the period.

In 1821, Athens was a minor, provincial city, but its association with the admired “good Greece” of antiquity was decisive in its ultimate selection as the nation’s new capital. Kostantaras’ research situates Greek independence from Ottoman rule in an “age of revolutions,” affecting many other parts of Europe and the European colonial world, in which social, constitutional and national grievances came to the fore—sometimes simultaneously. As such, the Greek revolution was subject to the kind of internal divisions found elsewhere.

“Revolutions are messy in the sense that the interests and aims of those involved don’t always cohere,” Kostantaras says.

The Greek revolution has an enduring legacy. “It was enormously important in establishing the idea of the nation-state as a basic rudiment of a new international state system,” Kostantaras says. “Western powers were dragged along kicking and screaming, but by intervening to help establish an independent, new Greek nation-state, they did a lot to promote the idea that nationality was a legitimate basis for sovereignty.”

This aid from abroad was not always forthcoming, but the “national problem” continued to be a source of considerable controversy and strife in Europe for many years.

“Whether abetted by the forces of revolution, war or diplomacy, the political geography of the continent would be radically reconfigured in what strikes many as a relatively short period of time,” Kostantaras says.

Southern Discomfort

September 1821 marked the end of Mexico’s war of independence from Spain. The year also ushered in unrest and rebellion across Latin and South America. Although some of the wars raged until 1825, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru and Venezuela declared independence from Spain in some form in 1821.

“The view of humanity from 10,000 feet in the nations that declared independence from Spain and Portugal in 1825 reveals a kaleidoscopic array of colors and shades that comprised the various races of colonial society—indigenous, African and European, as well as an infinite variety of intermixing through cultural and biological miscegenation,” the latter referring to mixing of races, says Peter Klarén, professor emeritus of history and international affairs.

“Over the course of three centuries, skin color determined one’s place in the society—that is a rigid caste system that underpinned the colonial order. With independence and the formation of a new Republican order came the promise of a new social order based on liberty and equality,” Klarén says. “Although progress to this end remained painfully slow in the post-independence era.”

The 1823 Monroe Doctrine was a “hollow threat,” since the United States couldn’t back up its demand that Europe cease meddling in the Americas. That was the case when France invaded Mexico and placed Maximilian I of Austria on the throne in 1862. “However, the policy took on more meaning a century later during the Cold War and beyond, first aimed at the Soviet Union’s designs on Cuba, and today perhaps at China’s ambitions in the region,” Klarén says.

For its part, Mexico faced a long, tumultuous period of disintegration following its 1821 independence, including losing a third of its territory to its northern neighbor in the Mexican-American War of 1845-48.

“Now more than a century later, after a long and continuous process of migration northward beginning with the 1910 Mexican Revolution, Mexicans have a renewed demographic presence in the American West and Southwest and with it a profound impact on American politics and culture, particularly in California where Latinos now comprise 40 percent of the population,” Klarén says.

For its first 30 years, the United States was “one of the lone democracies in a sea of monarchies,” according to Anbinder. “The fact that other peoples in the Americas were throwing off their colonial rulers and becoming independent nations made Americans very happy,” he says. “They felt like if republics become the rule rather than the exception that foreign powers would be less likely to try to destroy the United States.” Two hundred years later, more than half of the world’s nations are democracies, by many counts.

“A lot of things were coming together at that time for sure,” Brunsman agrees.

Menachem Wecker, M.A. (art history) ’09, is a freelance writer in Washington.

Documentary Film Series

Explore the evolution of GW across the 200 years since its founding in 1821: Watch GW at Two Hundred and keep an eye out as more films are released throughout GW's Bicentennial Celebration.