A Life of Verse and Service

A Life of Verse and Service

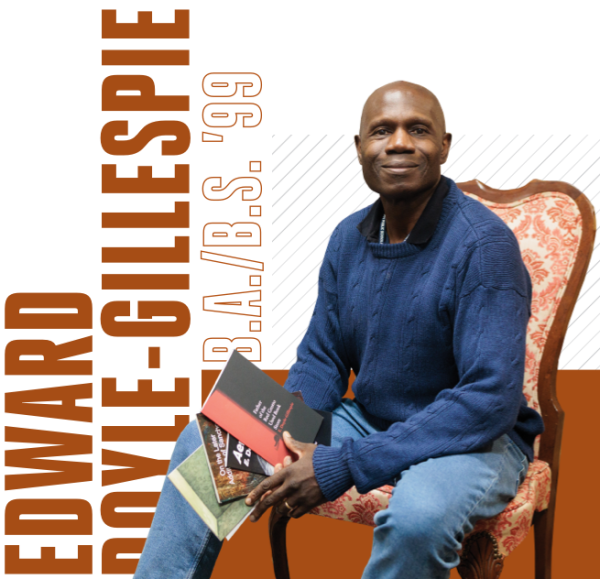

Former Baltimore police officer Edward Doyle-Gillespie draws on his years in law enforcement and his love of language to inspire students and shape his poetry.

/ / by Mike Unger

Edward Doyle-Gillespie, B.A. ’92, has had a challenging day. A student in the language arts class he teaches at the Baltimore Leadership School for Young Women called him “rude.” In his previous life as a police officer in Baltimore, where he walked the beat in some of the city’s toughest neighborhoods, he’s been called a lot worse.

But Doyle-Gillespie is a sensitive, thoughtful man, and on a mild September evening, he contemplated the similarities between his current job, his former one and his other passion—poetry.

“Some days I think it was easier getting shot at,” he joked while sipping a Portuguese iced coffee. “But you do realize there’s some common threads. Everyone is playing chutes and ladders on Maslow’s hierarchy. I’ve seen that in the millionaire kids that I taught and the destitute people that were living in abandoned houses. I found that people are, at the same time, simplistic and essential and elemental and more complex. I guess that’s a way to say it.”

In conversation, Doyle-Gillespie has the same eloquent, insightful way with words that can be found in his writing. He’s published five books of poetry, was the grand prize winner of the 2024 Iridescence Award and won honorable mention in the 2023 Rhonda Gail Williford Award for Poetry for his work, “Third Lunch Alone in Sydney.”

The son of teachers, Doyle-Gillespie grew up in Philadelphia immersed in literature. A history major at GW, after graduating in 1992 he became a teacher himself, first in Ohio, then at a prestigious private school in Baltimore. He was happily married, writing poetry and just starting graduate school at Johns Hopkins University when the 9/11 terrorist attacks changed the trajectory of his life.

“That was kind of a Pearl Harbor moment for me,” he said. “I'd read a lot and talked a lot and theorized a lot about Western culture and freedom and individuality and humanism. I consider myself a humanist, and this was a time to really make that material. And so I wanted to find service of some sort.”

Out of the blue (and despite some serious trepidation from his wife), he joined the Baltimore Police Department. It was, not surprisingly, harrowing, dangerous work, but he took from it the sense of purpose for which he had been searching. Over the course of his 19-year career he worked as a patrol officer, in the larceny from auto theft unit, in intelligence, as a troubleshooter on the deputy commissioner's staff, and as an instructor at the police academy. Once, a drug dealer put a hit out on him, he said.

“I was walking up a stairwell to assist a social worker and next thing there's bullets ricocheting out all around my head,” he said. “I've been hit by multiple cars. Fallen down some stairs.”

But he lived to tell about it. Writing poetry, Doyle-Gillespie said, helped him filter some of what he experienced.

In “Final Hajj,” he writes of watching a man die at a crime scene.

Part of what he loves about the art form “is the essential nature of the language and the brevity. It has to be brief and expansive at the same time. If you hit the right chord, you unwrap this box for the reader.”

“…He has only a small hole from the girl’s kitchen knife over his heart, but his body will erupt with a raspberry tide when the residents down at Maryland General crack his chest to practice the alchemy of resurrection. They will fail, unable to make the quick out of the dead, and I will gather his clothes--baggy layers of ghetto soldier uniform--heavy with blood, and document them on a Police Form 56.”

Edward Doyle-Gillespie, B.A. ’92, from his poem “Final Hajj”

The job, while rewarding in some ways, was taking a toll on Doyle-Gillespie’s mental health. He began suffering from PTSD, anxiety and depression. His perspective changed when his daughter, Piper, was born in 2011.

“When I first became a father, I immediately started seeing things through a different lens,” he said. “I was sitting there in the wreckage of my last police car with glass all over me with an airbag deployed in my face and thinking, ‘Yeah, this is getting a little old. I'd kind of rather be home reading Dr. Seuss.’”

In 2024, Doyle-Gillespie retired and got back into teaching. Like all jobs, it has its share of ups and downs, but in working with the 15- and 16-year-old girls, he finds the same sense of purpose that fueled his career in law enforcement.

Doyle-Gillespie still writes poetry, has spoken about his work at literary events and on college campuses throughout Maryland and still sees poetry everywhere in the world. He recalled a time when in a police station he was alone outside a cell that contained a man he had just locked up.

“The walls there were painted this industrial blue-gray,” he said. “I heard the guy go, ‘Yo man, look at that.’ I looked and there was a grasshopper just sitting on the wall. He’s in a cage, and I'm outside, and we're both just staring at this. And he said, ‘Dang, I almost missed it.’ I said, ‘Yeah, so did I. I would have missed it if you hadn't said anything.’ And then we just kind of watched as it dropped away.”

He’s still processing that story, but he’s pretty sure it will be—in one shape or form—part of one of his future poems.

Photography: William Atkins