Generations: Stitches in Time

By Menachem Wecker, MA ’09

Six years ago, a crater on Mars was given the name Oyama, and tens of millions of miles were added to the story of one family’s spread—from Japan to the U.S. to internment camps, to freedom and, now, to a far-flung world.

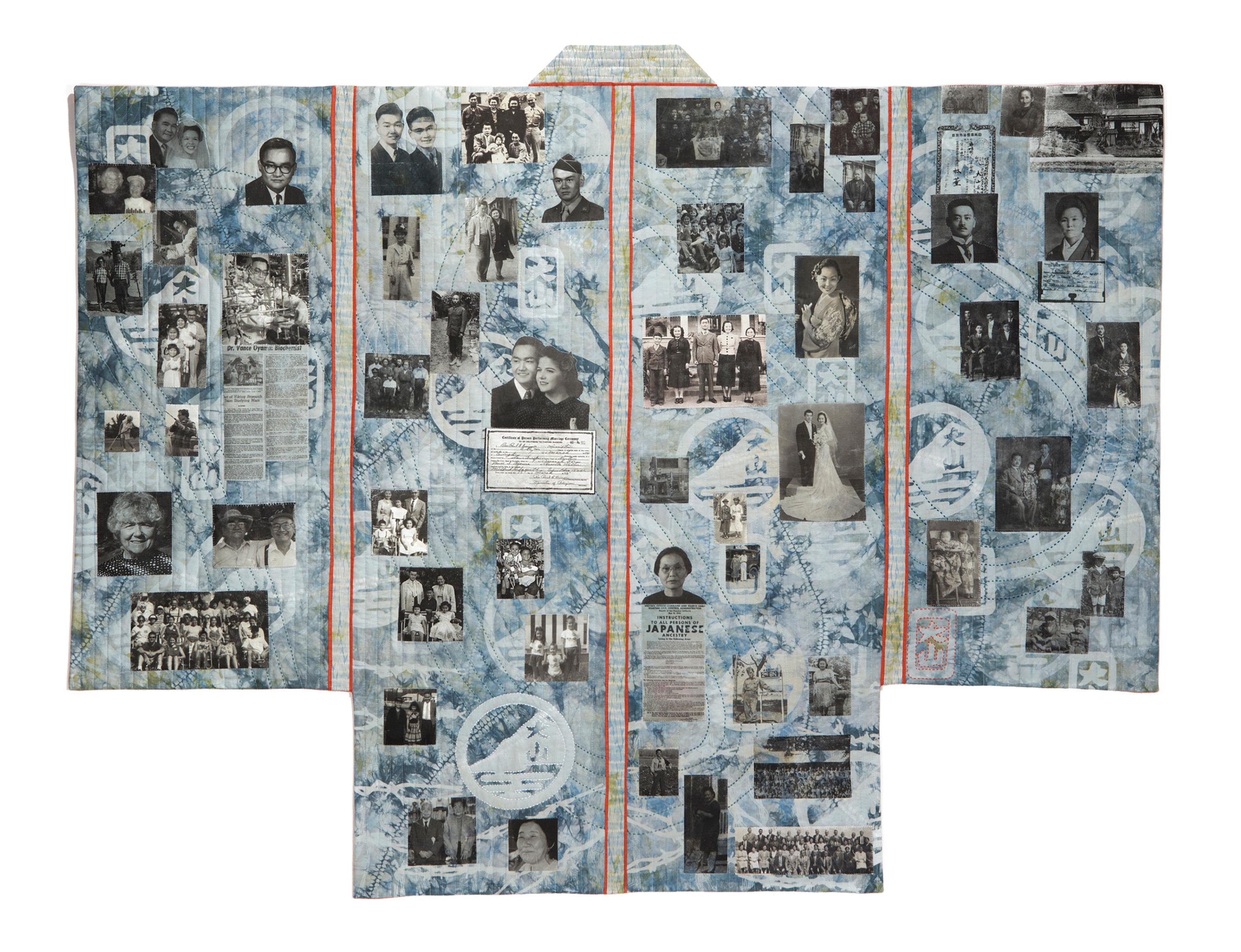

The narrative of NASA biochemist Iwao “Vance” Oyama—who received a master’s degree from GW in 1960—and his wider family is captured by his daughter Denise Oyama Miller in a quilt called “Connecting Threads,” part of a GW Museum and The Textile Museum exhibition, Stories of Migration: Contemporary Artists Interpret Diaspora (through Sept. 4).

The Fremont, Calif.-based artist’s work, in the shape of a kimono, tells the Oyama family’s diasporic story, beginning with Ms. Miller’s grandparents, Zengoro and Chiyo, who met and married in Honolulu after emigrating separately from Yokohama, Japan, in 1907 and 1911, respectively. The two settled in Los Angeles, and after Zengoro’s death in his early 50s, Chiyo raised their four children and ran the family’s storefront, a “little mom-and-pop dime store,” Ms. Oyama says.

The family would lose the store, and its home, after the attack on Pearl Harbor and President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1942 order to relocate some 117,000 people of Japanese descent into camps. The Oyama family was sent to Arkansas, but Vance went to work in Montana under Quaker sponsorship. Vance’s younger brother Jiro, MS ’56, PhD ’60, was drafted in 1944 and assigned to Japan in the reconstruction period. After stints at the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Jiro spent 28 years at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California, where, among other things, he studied the physiological effects of altered gravity.

Vance Oyama met Ms. Miller’s mother at an Ohio munitions plant, and in 1945, the two married in Kentucky, Ms. Miller says. Further details surrounding the marriage—including whether they had left to escape anti-miscegenation laws or sentiment—are hazy, she and Jiro say. “It is somewhat painful to recall,” Jiro says.

Vance, who died in 1998, notably was involved in NASA’s search for life in lunar soil samples returned by Apollo 11 and, later, as part of the Viking probes that landed on Mars in 1976.

“JAPAN HAS SUCH A RICH TEXTILE-FABRIC HISTORY. [AND] WE HAVE A VERY STRONG QUILTING FIBER HISTORY IN THE UNITED STATES,” SHE SAYS. “I THOUGHT THERE WAS DEFINITELY A WAY TO BE ABLE TO COMBINE THEM TO FIND A WAY TO HAVE THE FEEL OF JAPAN BUT THE INFLUENCE OF THE UNITED STATES AS WELL.”

Ms. Miller realized that she wanted to pursue her family’s story in art after family members seven years ago began gathering regularly to discuss the history. How to capture all that, though, didn’t become clear until she saw a call for art from the Studio Art Quilt Associates for the GW museum show. “It just sort of hit me, like, ‘Yes! Our story is about a diaspora.’ And we are not the only ones who went through it,” she says.

The more difficult parts of the family history, pertaining to the camps, required some extra research. “My dad’s generation didn’t like to talk about that. I think that’s pretty universal,” Ms. Miller says. “They were so mortified, I think, from being imprisoned and having their rights taken away for no reason that they were ashamed of it.”

The chronological family story—which reads, like Japanese, from right to left along the work—represents a melding of Japanese and American art-making traditions.

“Japan has such a rich textile-fabric history. [And] we have a very strong quilting fiber history in the United States,” she says. “I thought there was definitely a way to be able to combine them to find a way to have the feel of Japan but the influence of the United States as well.”

For the kimono, Ms. Miller began with a white cotton fabric that she dyed using a traditional Japanese technique called shibori, then used Thermofax screens to remove some of the dye to reach a specific shade of blue. Hand stitching was done using the Japanese sashiko style, a machine was used for the quilting and photos were applied using Transfer Artist Paper.

Ms. Miller, who attended her father’s GW graduation as a child, appreciates how things have come full circle with her work on view at GW. “I thought, ‘Oh my god, it’s all coming together,’” she says.

And the intense focus on her family has led to another planned work that will center on her mother and her decision to marry a Japanese man in 1945. “That was a pretty amazing time for an Indiana farm girl to marry a Japanese man. I don’t think either family was really thrilled about the event,” she says. “I think she would have been a great women’s libber, but she was born in the wrong time period.”