Deep-Fried Adventures in American History

“Drive-Thru Dreams” author Adam Chandler, BA ’05, details the joys and challenges of writing a book about fast food.

By Adam Chandler, BA '05

Over the course of the past year, I’ve been asked a variation of this important question: “How did you become the preeminent scholar on fast food?” It’s a good question, a generous one, especially when the person asking isn’t also laughing at me.

The truth is that I don’t have a good answer. Were I to channel Marianne Williamson, I might dreamily suggest that we’re actually all fast-food experts. After all, in a given year, 96 percent of Americans eat fast food—more people in the United States eat fast food annually than use the internet—and 80 percent of Americans eat it monthly. Before the CDC had considerably bigger potatoes to fry, they issued a depressing report noting that, every single day, a little over one-third of the country eats fast food.

It’s statistics like these (as well as an abiding love for Taco Bell Crunchwrap Supremes) that drew me to

write a book about the topic. Of course, we already know why people hate fast food. Over the past few decades, countless public intellectuals, labor advocates, nutrition scolds and environmentalists have rightly taken aim at our beloved chains.

What I wanted to know is why people love it. Why are the bright fluorescent lights of fast food dining rooms a constant venue for prom photos, marriage proposals and even weddings? Why did an Alabama town hold a candlelight vigil after the local Taco Bell burned to the ground? Why did an 8-year-old Illinois boy teach himself how to drive by watching YouTube tutorials and drive himself and his 4-year-old sister to McDonald’s? Did Rahm Emmanuel really lose part of his middle finger to an Arby’s meat slicer?

To report it out, I drove across the country eating my weight in nuggets and sliders and talking to everyone from franchisees and corporate minders to workers and fast-food obsessives. In a small town in Kansas, I met a group of retirees who gather at a Burger King every morning to study the Bible and exchange gossip over coffee. I was heckled by a crew of bored teens at a McDonald’s in Iowa because I ordered a salad. I saw stressed parents enjoy a moment of reprieve while their children wore themselves out on the indoor playgrounds. What I found is that fast food offers borderline narcotic fare, but also comfort, community, ritual and nostalgia.

From a zoomed-out view, fast food is an uncanny reflection of the mainstream. It intersects with the social, cultural and political history of American life. The creation of chains, whether it’s McDonald’s, In-N-Out or Whataburger, were the byproducts of the post-war boom, car culture and the building of the highways, the fashioning of the suburbs and the birth of the commute as well as the rise of dual-income households. As the work days grew longer and wage growth stalled, a $5 dinner served through a window and eaten while driving became less of a novelty and more of an everyday convenience.

It’s this attunement to the frequencies of daily life that makes fast food such an American institution. The big chains are rightly criticized for being monoliths that throw around their purchasing and marketing power, but they’re also strangely adaptable to consumer desires and mores. Think of, for example, the millions of Americans who will have their cage-free egg by way of an Egg McMuffin or their first plant-based burger by way of the Burger King Impossible Whopper.

In a contemporary context, this relevance is culturally powerful. Fast food is a regular shorthand for how we talk about worker wages, health, the environment or the habits of American families that are strapped for time and cash. This summer as social-justice protests expanded across American communities, several major and previously reluctant chains took the step of making statements in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. These maneuvers were a testament not to the political courage of fast-food chains, but to their constant gauging of public opinion, which now reflects a major shift among Americans from previous years.

That relevance makes fast food oddly indispensable by design. When they’re open, places like McDonald’s dining rooms are the rare places where people of all backgrounds, ages, and income levels gather. Now that they’re overwhelmingly closed, millions of families, frontline workers, and truckers rely on the drive-thrus for something quick, affordable and familiar during the pandemic. For better and often worse, the American landscape isn’t quite right without burgers, fries and roadside marquees.

Here, Adam Chandler annotates the first two pages of Drive-Thru Dreams, giving you a behind-the-keyboard look at how part of his book came to be.

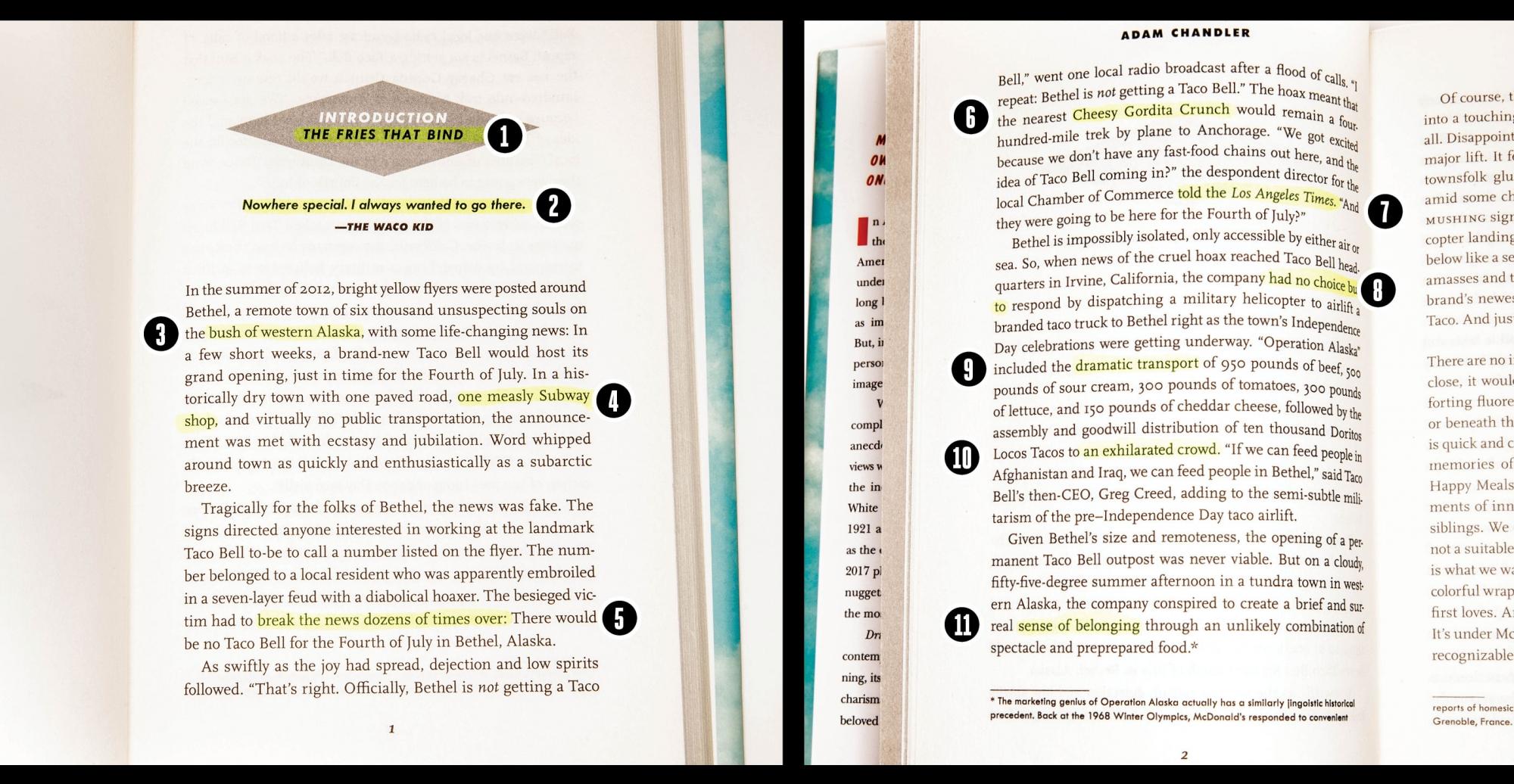

- About halfway through writing the book, I decided I wanted to the title to be a truly terrible pun that spoke to the universal nature of fast food in America. My editor wisely overruled me, but let me use it as the intro title instead.

- I start each chapter with a small, theme-setting epigraph. While writing, it helped me from straying too far. In this instance, Gene Wilder’s quote from the end of Blazing Saddles conveys the allure of a completely unremarkable place.

- We often think about fast food in terms of its ubiquity, especially in America. For me, there was huge appeal in starting the story in a place in the U.S. where there is no fast food or conventional car culture.

- Blech.

- Truth really is stranger than fiction.

- A Top 10 item in the entire fast-food universe.

- Believe or not, this story did make national news.

- In addition to the history and politics that surround the big chains, it’s important to consider the culture of fast food. Not only are there deep levels of loyalty and obsession, but also some very savvy brand marketers that work to cultivate fandom.

- Taco Bell’s gambit here was actually borrowed from one performed by McDonald’s during the 1968 Olympics. Responding to convenient reports of homesickness among U.S. athletes, the company airlifted a cache of hamburgers into Grenoble, France.

- This stunt eventually did become a Taco Bell commercial. (It’s pretty easy to find online.)

- Destinations like Taco Bell inhabit the role of a “third place,” where people meet and gather outside of work and home. This is part of what makes fast food spots such useful tools in understanding the communities that surround them.

Adam Chandler, BA ’05, is the author of Drive-Thru Dreams (Flatiron/Macmillan, 2019), which was named a Best Book of the Year by NPR, Amazon and Smithsonian. A former staff writer at The Atlantic, Chandler’s work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Slate, Vox, Esquire, Texas Monthly and elsewhere.