Bookshelves Winter 2025

Alan Siegel, B.A. ’05, senior staff writer at The Ringer, started watching “The Simpsons” around age 7. When he had dinner with his freshman-year roommates that first night at GW, the show provided common ground. The cake topper at his wedding: Milhouse Van Houten and Lisa Simpson. Now, after years of writing about the show, Siegel’s first book, Stupid TV, Be More Funny: How the Golden Era of The Simpsons Changed Television—and America—Forever (Hachette, 2025), covers the influential show’s rise through its 1990s glory years. He talked with “GW Magazine” about the show’s place in popular culture—yes, 36 years later, it’s still on the air—and in his life.

Q: You said people between the ages of 35 and 55 have a special relationship with “The Simpsons.” Why is that?

A: We truly were raised on it, and I think partially that's because it was on every week and because of syndication. By 1994 or so, it was on all the local Fox affiliates, like twice a night. We would come home from school, watch it or watch it with dinner. It was really ingrained in a way that other shows maybe weren't. It was as close to ubiquitous as any show was of that era.

Q: How did the show shape you?

A: It made me curious about other things. If I saw an [Alfred] Hitchcock reference or a [Stanley] Kubrick reference when I was eight or nine or 10 or 11 years old, I didn't get it. But it made me curious about what the show was referencing.

Q: Your book covers “The Simpsons” from roughly 1989 to 1998. Why that timeline?

A: I think the ’90s era of the show was the absolute best. It’s a tidy narrative to stick to one decade and what it meant for the show and for the country. I think the show as it is currently constituted is good. It’s sort of a victim of its own success. The beginning was so good that it’s really hard to live up to that era. And it’s no fault of anyone’s that it’s just not quite at the level of influence that it was for so long.

Q: What’s the show’s place in popular culture now?

A: What’s crazy is now it’s an American institution. It’s on postage stamps, in the Library of Congress. It’s been immortalized as this pillar of American popular culture like “Peanuts” or “Saturday Night Live.” What that does is kind of sand the edges off. People thought the show was incredibly dangerous, including my parents who are liberals from Boston. They relented. They began to understand. On “Leave It to Beaver,” the kids were not saying sucks and damn to adults. I think that scared a lot of parents into thinking what Bart Simpson would encourage their kids to do.

Q: Was there a moment when America embraced “The Simpsons”?

A: It's hard to pinpoint, but I would say after the ’92 presidential election. You had George H.W. Bush saying multiple times on the campaign stump, “We need more families like the Waltons, less like the Simpsons.” And the Waltons were New Deal Democrats. It took maybe four seasons for the public to realize that this was a family show. It had subversiveness and edginess, but it had pretty traditional values.

Q: Can a show have that kind of impact now?

A: I don't know that it’s impossible, but it's much, much harder to do. It’s a cliche to talk about the death of the monoculture, but in its first couple seasons, 20, 30 million people are watching “Simpsons” episodes every week. I think the viewing audience is just too fractured to really embrace something together like we used to do.

Q: Talk about your time at GW.

A: Even from the very beginning, I loved going to school in D.C.: the ease with which we could move around, take the Metro everywhere. We had a flag football league. We played down on the Mall by the monuments. You sort of take these things for granted after you go to school there for a little while. I think the most important thing was writing for the Hatchet, the school newspaper. That gave me real-world experience. We published twice a week, but it was right at the start of the online media revolution. We would update almost every day. I was a sportswriter, sports editor back then. That experience for three years there really set me on the path to where I am. I’d say that’s where I fell in love with journalism.

"Launching Liberty: The Ships That Took America to War" (Simon & Schuster, 2025)

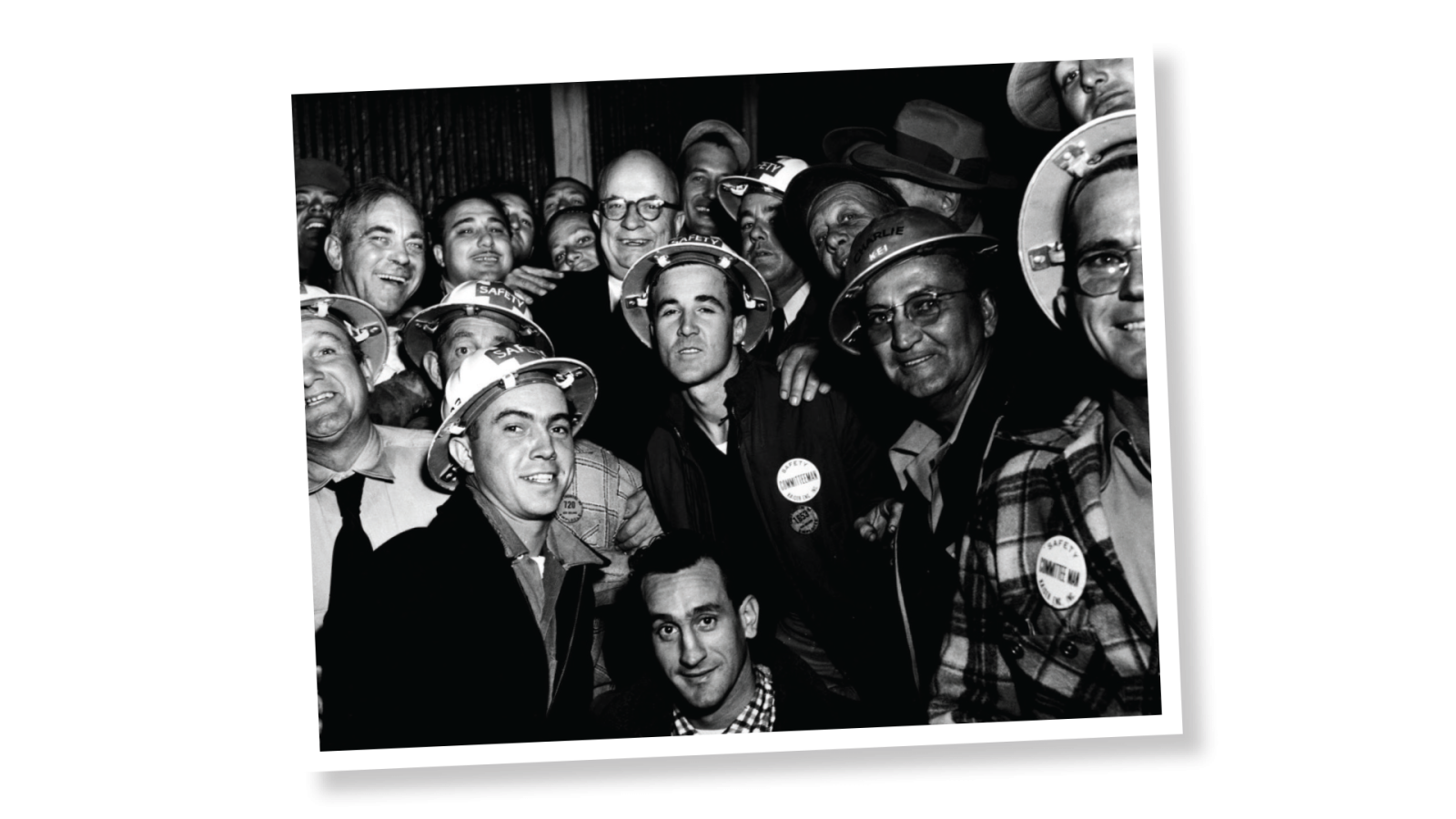

Doug Most's, B.A. '90 new book, “Launching Liberty: The Epic Race to Build the Ships That Took America to War” (Simon & Schuster, 2025), tells the story of the men and women who powered President Roosevelt’s Arsenal of Democracy. Here are some photos that illustrate key moments and milestones in Most’s book.

The partnership between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the American industrialist Henry Kaiser (here at a ship launching celebration) was key in the administration’s emergency shipbuilding program, which produced more than 13,000 vessels during the war, including more than 2,700 Liberty ships.

Henry Kaiser was beloved by his workers because he paid them fairly and provided them health care. His on-site health plan, started in the 1930s during Boulder Dam construction, evolved into Kaiser Permanente.

Launched from Baltimore in 1942, the SS John W. Brown remains one of only two Liberty ships still afloat (the other: SS Jeremiah O’Brien in San Francisco). Like every Liberty ship, it measured precisely 441 feet and 6 inches long and 57 feet wide. The ship completed 13 wartime voyages. Tours showcase its deckhouse, cargo holds and powerful engine room.

Gladys Theus was among the fastest welders at Kaiser’s shipyards. Women, known as “Wendy the Welder,” proved especially skilled for the job’s precision demands and competed for honors, with top welders visiting First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House.

The partnership between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the American industrialist Henry Kaiser (here at a ship launching celebration) was key in the administration’s emergency shipbuilding program, which produced more than 13,000 vessels during the war, including more than 2,700 Liberty ships.

Call it the Boston Coffee Party.

On a July morning in 1777, a crowd of women gathered in front of a Boston warehouse. It was just a year after the Declaration of Independence and two years into the Revolutionary War. The city under siege was being strangled by British taxes and supply chain shortages. The restless colonial women demanded the merchant hand over desperately needed provisions—not muskets or saltpeter but coffee.

“We’re so used to hearing about the tea party—but this is the coffee party,” said George Washington University alumna Michelle Craig McDonald, M.A. ’94, librarian/director of the Library & Museum at the American Philosophical Society (APS) in Philadelphia.

In her book “Coffee Nation: How One Commodity Transformed the Early United States” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2025), McDonald serves up the story of how coffee awakened the fledgling nation’s revolutionary spirits. From the first coffee grinders carried on the Mayflower to the slavery-based plantations of the Caribbean and South America, McDonald describes coffee, for better or worse, as a staple of the American legacy.

George and Martha Washington drank it. So did John Adams—reluctantly. Jefferson served it at Monticello, and Ben Franklin sampled it in France. Throughout the colonies, coffeehouses were hotbeds of revolutionary fervor, hosting debates over Stamp Acts and Townshend Duties. Philadelphia’s first coffeehouse opened in 1703; Boston’s in the 1690s. They operated as businesses, banks, even bars.

“Coffee is part of the story of America,” McDonald said. From founding fathers to provincial patriots, “they all drank it.”

For McDonald, whose research focuses on North American and Caribbean trade during the 18th and 19th centuries, coffee also brews up a challenge to traditional interpretations of the American Revolution—and the American character.

Colonial coffee was mostly produced in the Caribbean. The drink’s profitability and popularity thrust the U.S. into the global economy. By the mid-19th century, America dominated coffee consumption and trade—despite every bean brewed there coming from somewhere else.

“U.S. citizens have long seen themselves as an independent and industrious people,” McDonald said. “In a sense, coffee flips our idea of independence on its head. Coffee isn’t a story of independence—it’s one of interdependence.”

Percolating Patriotism

For McDonald, her role with the Library & Museum at the American Philosophical Society is a culmination of a 30-year career as a historian, educator and administrator—even if, as she joked, “I’m neither a librarian nor a philosopher.”

A museum studies major at the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, McDonald has worked at universities and with museums and historic sites from Colonial Williamsburg to the African American Heritage Museum of Southern New Jersey. At APS, she curates over 14 million pages of historical manuscripts including handwritten copies of the Declaration of Independence and the original journals of Lewis and Clark.

At GW, McDonald learned how to tell stories through material culture in cases where documents were absent. “Objects fill in the gaps where written words weren’t kept or collected,” she said. “They are an important lens through which to understand societies, their history, beliefs, social structures and identities.”

In coffee, she found a subject that historians have often overlooked. Numerous studies of early Atlantic trade have focused on sugar or rum, especially in connection with the transatlantic slave routes. But despite coffee’s widespread consumption—U.S. imports grew from 4 million pounds in 1789 to 53 million just five years

Briefly Noted

"The Very Heart of It: New York Diaries, 1983-1994" (Penguin Random House, 2025)

by Thomas Mallon, professor emeritus

In his latest book, Mallon publishes a collection of his journals from the 1980s and ’90s, chronicling his emergence as a writer and gay man in New York during the AIDS crisis. Through vivid, intimate entries, Mallon captures the highs and lows of a transformative era—his growing literary success, encounters with cultural icons, and the profound personal losses that shaped both his life and work. “This is a chronicle of sex and death; of lovesickness and eventual joy; of friendship and gossip; of political fervor and ambivalence; of ambitions both frustrated and fulfilled; and of a now vanished literary life,” he writes in the preface.

"The Room at the End of the Hall" (Carroll Press, 2025)

by Susan McCormick, M.D. ’88

In McCormick’s medical mystery, Michael Baker, a gifted surgeon, moves home to Seattle to care for his estranged, alcoholic mother—not entirely out of compassion. Almost immediately, his life starts to unravel: a patient dies, another lands in the ICU, a colleague is injured in a mysterious fall. His mother is convinced there’s a murderer afoot, but she is far from reliable. In this twisty thriller, McCormick weaves a tale of guilt, obsession and the thorny relationship between mothers and sons.

"Something Big: The True Story of the Brown's Chicken Massacre and the Search for Justice" (Post Hill Press, 2025)

by Patrick Wohl, B.A.’16

Wohl revisits one of Chicago’s most shocking crimes in his new book. Drawing on two years of research and more than 40 interviews, the attorney and author explores the 1993 murders of seven people at a Brown’s Chicken restaurant—not to sensationalize the violence but to honor the lives affected by it. Wohl, who grew up near the crime scene, focuses on the grief, resilience and humanity of victims’ families, law enforcement and even former suspects. His book also reflects on the evolution of DNA technology, modern policing, and the ethics of the true-crime genre, challenging readers to reconsider how such stories are told.

Photography: William Atkins. Sources for "Launching Liberty" archival photos (top to bottom): courtesy of Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources; courtesy of Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources; Howard Liberman for the U.S. Office of War Information, Farm Security Administration collection, Library of Congress; Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, photo no. 65727-49; courtesy of Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources.