Bookshelves Winter 2024

Bookshelves

‘It Is Fundamentally Wrong’

Alumna painstakingly chronicles the brutal and surprising history of the for-profit prison system.

In the early 19th century, three men in Auburn, New York, landed on the idea of a prison as a means of enriching themselves and their nascent village. In these men’s eyes, a prison was a way to attract state funds, grow commerce and employment, and—with repercussions that have lasted for two centuries and counting—manufacture goods with free labor.

So sets the stage of “Freeman’s Challenge: The Murder That Shook America’s Original Prison for Profit” (University of Chicago Press, 2024), the extraordinary new book by Robin Bernstein, M.A. ’99, that brings to painful and vivid life the origins of a system that continues to serve as a model for prisons everywhere.

What came to be known as the Auburn System had a clear goal of profit over redemption or justice. Prisoners toiled all day every day in factories on the premises. Infractions real or perceived were met with extreme violence.

After serving five years in Auburn for a charge he denied, a Black man, William Freeman, demanded payment for his labor. The lengths he went to, including multiple murders, shocked Whites and Blacks alike—and resonate to this day.

GW Magazine talked to Bernstein, the Dillon Professor of American History at Harvard University, about the legacy of Auburn, what she wants readers to take away, and how what she learned at GW informs her research and teaching.

Q: How did you come across the story of William Freeman, and what drew you to tell his story?

A: I saw a footnote about a 1846 theatrical performance in Albany, in which a Black character killed a White family. I knew that something extraordinary had happened. In the 19th century, White people absolutely did not want to see images of Black-on-White violence. It was too frightening. And yet in Auburn, people were lining up and paying money to see it. I found that the performance was a dramatization of Freeman’s story. I started researching him and learned he had been incarcerated in Auburn in the 1840s and forced to work in factories where his labor was leased to local companies.

I had thought, like so many, that prison for profit and convict leasing were invented by the South after the Civil War as a way of re-enslaving Blacks. However, the system was created much earlier in the North. When we start the story of the prison for profit with the South and the Civil War, we’re starting the story in the middle. And the problem with starting the story in the middle is that it lets the North off the hook. I wanted to put the North back on the hook.

Q: How has the Auburn System influenced the development of for-profit prisons?

A: It was the primary influence. It established the idea that a prison can function primarily and fundamentally as an economic force. It’s a bizarre idea, but there is no prison in the world that is not affected by it. When we think about some of the most famous prisons in the United States—San Quentin or Angola—they were self-consciously created in Auburn’s image.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: I hope they take away a sense of the weirdness of the idea that a prison should be an economic force. Why should anybody profit economically off another person’s incarceration? I also hope people take away a respect for William Freeman’s bravery and for his core point that it is fundamentally wrong to steal somebody’s labor. He was a teenager, and he was in prison for a crime he swore he did not commit. We might not approve of his methods of resistance, but he resisted bravely, and he tried to resist legally.

Q: How do you reconcile the murders Freeman committed with his bravery and the justice of what he was demanding?

A: The way I think about the murders is that they were an act of terrorism, and what we know about terrorism is that it succeeds in terrifying. It’s very important that the murders do not fit into an easy, narrow, revenge narrative. If they had, it would have been much less terrifying. But because it denied people the comfort of an easy ending, they had to grapple with the crime. What they did not want to do is listen to what Freeman was saying. So they had to come up with their own story about why Freeman killed these people. And the story they came up with was race. White people in Auburn made the racist argument that Freeman killed because he was Black (as well as Native American). This is one of the earliest criminalizations of Black people, one of the most vicious forms of racism that we continue to live with today.

This criminalization explains why White people in Auburn, unlike their counterparts elsewhere, wanted to see Black-on-White violence on stage. As frightening as this story was, it reinforced a newly formed racist libel that itself was a means for White people to manage the terror they felt when William Freeman challenged the Auburn prison.

Q: Finally, could you talk a bit about your GW experience?

A: I got a master’s degree in American studies. I studied with Professors Melani McAllister and Gayle Wald, who are both still teaching at GW. They rocked my world! I still depend on what I learned in their classes every day for my research and my teaching.

– Rachel Muir

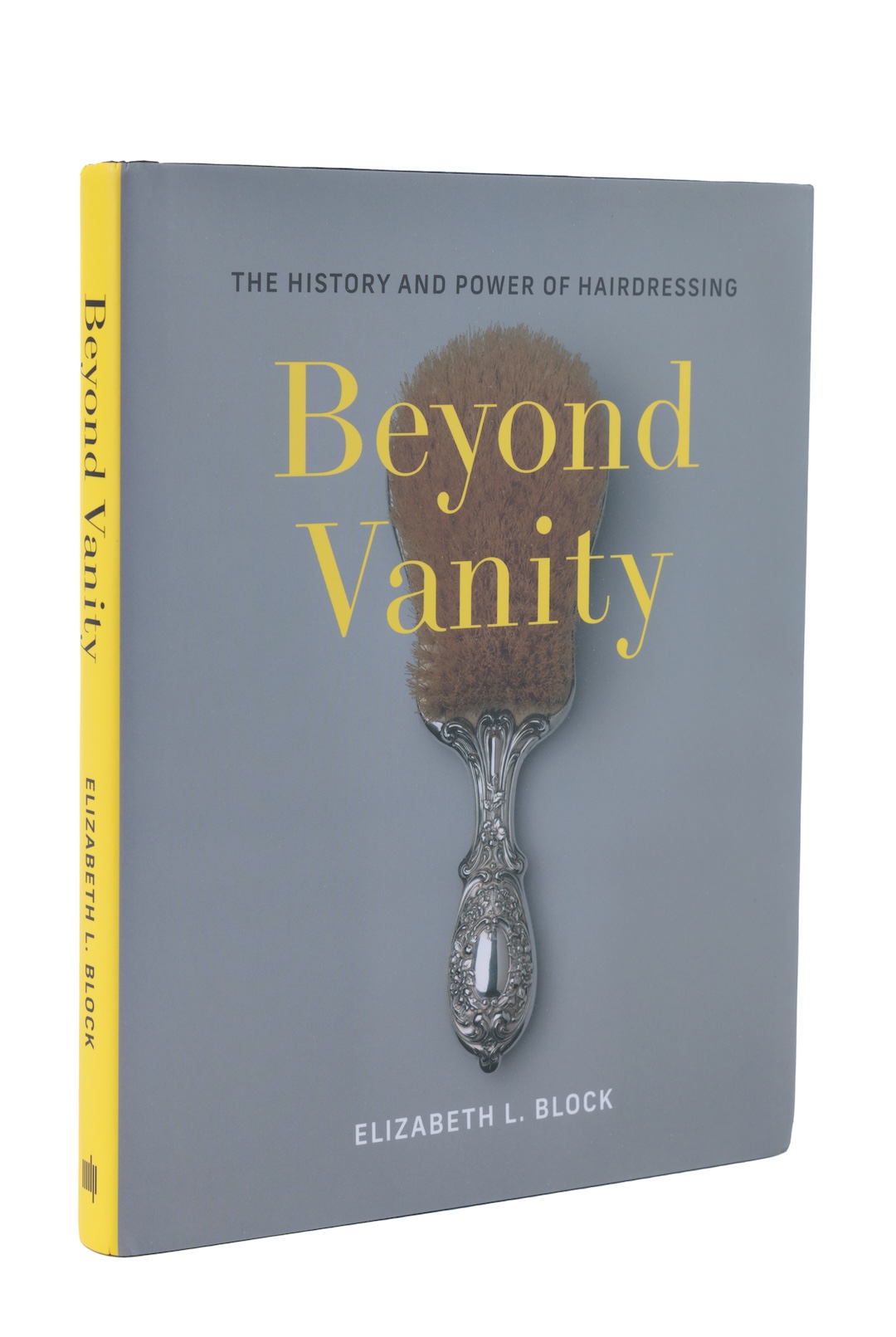

“Beyond Vanity: The History and Power of Hairdressing” (MIT Press, 2024)

Elizabeth L. Block, B.A. ’94

Block, a senior editor in the Publications and Editorial Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, combs (not literally) through the complex cultural meaning of late 19th-century hair in America. In the years after the Civil War, hair was inherently entangled in the social strata of the nation, influencing everything from ideologies to economies (and going so far as to include a taxidermized kitten headdress). Against a backdrop of high society salons, then called “hair rooms” or “saloons,” Block also uncovers the stories of Black and mixed-race business owners forging independent paths in the burgeoning hair industry.

“Plentiful Country: The Great Potato Famine and the Making of Irish New York” (Little, Brown and Company, 2024)

Professor of History Emeritus Tyler Anbinder

Anbinder and a small army of GW student research assistants spent more than 10 years following 15,000 immigrant names through troves of official records—through bank account balances, census data, and birth and death certificates. The result is a new immigrant story, one that traces their journey from the fields of Ireland to the streets of New York City while telling a wider tale that rescues Potato Famine immigrants from the margins of history and restores them to their rightful place at the center of the American story.

“After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” (Princeton University Press, 2024)

Professor of Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies and of Anthropology Eric H. Cline

A follow-up to Cline’s bestselling history “1177 B.C.,” “After 1177 B.C.” picks up at a point when many of the Late Bronze Age civilizations of the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean were in ruins, a result of a perfect storm of natural disasters, climate change, invaders and disease. Cline traces the aftermath across the region over four centuries—a time often referred to as the “first dark age”—as a new world order slowly emerged and, despite its moniker, inventions, including the use of iron and the alphabet, forever changed the world. “It is a story of resilience, transformation and success, as well as failures, in an age of chaos and reconfiguration,” writes Cline.

“Autocrats Can’t Always Get What They Want” (University of Michigan Press, 2024)

Elliott School Professors Nathan J. Brown and Julian G. Waller

Brown and Waller—and their co-authors Steven D. Schaaf and Samer Anabtawi—go beyond autocrats themselves to explore how the systems that support their regimes operate. Focusing on three structures—parliaments, constitutional courts and official religious institutions—the book’s authors find that autonomy hinges on forging key alliances both inside and outside the state and on developing strong institutional patterns. Those that do “are better equipped to realize a meaningful degree of autonomy over their internal affairs and may even be able to pursue their own sense of mission in politics,” they write. “The Half-Caste” (Polyphony Press, 2023) by Jason Zeitler, M.S. ’97 Zeitler’s new novel begins in 1930s London, where fascism is ascendant and war looms. Against this backdrop, two men forge an unlikely friendship over tea. But both Vernon, a mixed-race postgraduate student, and Saul, a Jewish intellectual, hold secrets back in their wide-ranging discussions. When the setting shifts to a bucolic jungle in Ceylon a decade away from independence, their secrets slowly come to light amid a backdrop of political intrigue, love and loss.

“The Half-Caste” (Polyphony Press, 2023)

Jason Zeitler, M.S. ’97

Zeitler’s new novel begins in 1930s London, where fascism is ascendant and war looms. Against this backdrop, two men forge an unlikely friendship over tea. But both Vernon, a mixed-race postgraduate student, and Saul, a Jewish intellectual, hold secrets back in their wide-ranging discussions. When the setting shifts to a bucolic jungle in Ceylon a decade away from independence, their secrets slowly come to light amid a backdrop of political intrigue, love and loss.