Bookshelves: A Metal's Mettle

(iStock.com/sdlgzps)

By Menachem Wecker, MA ’09

Brooke C. Stoddard, MA ’73, explores the metal that undergirds American might—a story thousands of years and thousands of degrees in the making.

Newspaper headlines in the mid-1980s centered on the U.S. steel industry’s challenges with trade,

unions and productivity. But while the rest of the country worried about steel’s future, Brooke C. Stoddard, MA ’73, was curious about much more basic questions: What is steel, and how is it made?

“I thought there was a big gap in the discussion,” he says. “A lot of people, including me, didn’t know what was going on in mills.”

Mr. Stoddard, who lives in Alexandria, Va., contacted the nearest integrated steel mill—the type that converts iron ore to steel—located near Baltimore. The mill agreed to host him, but couldn’t right away. So he headed to the Library of Congress for research. And the first two chapters of his book, published 30 years after the project began, attest to that legwork. The book methodically teases out the history of steel, from prehistoric meteorites to the present day, from Stone Age smiths to business tycoon Andrew Carnegie and Herbert Hoover, whose pre-White House resume included translating, in 1912, an important Latin text about metals.

“Steel made the industrialized world,” Mr. Stoddard writes. “It made railroads, bridges, skyscrapers, cargo ships, battleships, manufacturing machines, electricity grids, food containers, cars and trucks. Steel also made America a world power.”

Mr. Stoddard’s narrative ventures into the mills and the ships and beside the workers. Combined with the historical and modern contexts for steel, the result is a deep dive that remains accessible and relatable to the casual reader. It humanizes the subject.

“I love my job,” the general foreman of a blast furnace tells him, recalling how he entered the industry as a new dad after leaving the Navy. “The guy who interviewed me asked, ‘Are you afraid of heights?’ I answered, ‘No.’ ‘Of heat?’ ‘No.’ ‘Of dust?’ ‘No.’ ‘Sweat? Blisters?’ I kept saying no, and he said, ‘You’ve got a job in the blast furnace department.’”

Another man, with a “Santa Claus nose and steel-rimmed glasses,” whose “genes were a Scandinavian smorgasbord,” has fingers that are “stubby from a life’s work on engines, but the rest of him was trim.”

Even the machinery lurches to life. In a room that’s two football fields long and 10 stories high, hollow drums turn with “malevolent slowness at about the speed of a slow roll of the eyes; bolts protruded from their cylindrical inside walls like spikes.”

What’s revealed is something far more complex than cold, dead steel. “When you say the word ‘technology’ nowadays, everyone assumes you’re talking about something that has to do with digital information,” Mr. Stoddard says. “What I was trying to say in the book is that steelmaking’s a very sophisticated technology.”

But instead of manifesting as chips or wafers, he says, it’s skylines.

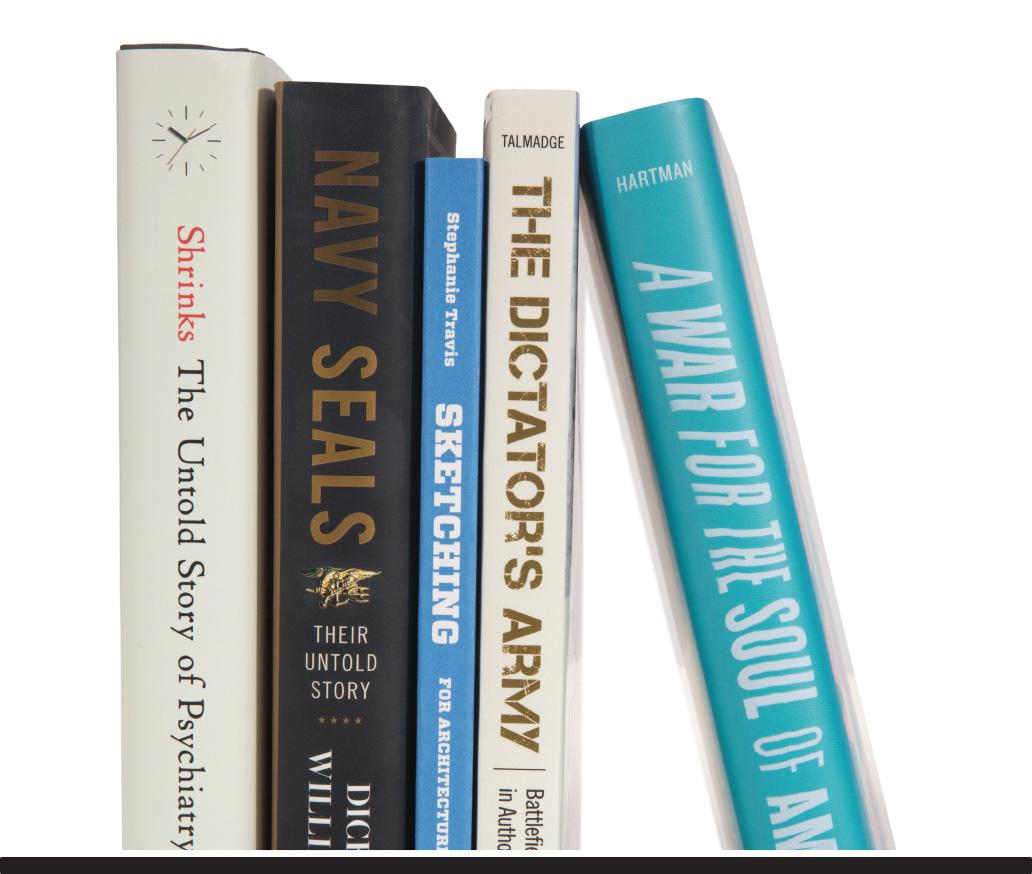

Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry (Little, Brown and Company, 2015)

By Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD ’75, with Ogi Ogas

“The profession to which I have dedicated my life,” Dr. Lieberman writes, “remains the most distrusted, feared, and denigrated of all medical specialities.” No anti-cardiology protesters decry that specialty, nor is there an anti-oncology movement that denounces cancer treatment, yet many see psychiatry as a mental health problem rather than a solution. That may have been true in the 1970s, but “For the first time in its long and notorious history, psychiatry can offer scientific, humane, and effective treatments to those suffering from mental illness.” Its “long sojourn in the scientific wilderness” is over.

Navy SEALs: Their Untold Story (William Morrow, 2014)

By Dick Couch and William Doyle, BBA ’85

A U.S. Marine at Saipan in 1944 reportedly, upon seeing the Underwater Demolition Teams’ (UDT) “swim trunks, baby-blue sneakers, and body paint,” remarked, “We ain’t even got the beach yet and the tourists are here already.” That style no longer outfits the UDTs’ successors, the Navy SEALs (Sea Air Land), who are notoriously secretive and whose “Hell Week” training continues to fascinate. That the authors managed to convince more than 100 former SEALS to share even parts of their experiences is very rare indeed.

Sketching for Architecture and Interior Design (Laurence King Publishing, 2015)

By Stephanie Travis, director of the Interior Architecture and Design Program

For those who bemoan that they can’t make a straight line, this book notes that drawing is really about seeing. “You are forced to pause and scrutinize, as drawing requires another way of thinking, shifting into a deeper realm,” Ms. Travis writes, noting that drawing is about trying to see things as if for the first time, rather than relying on what one knows is there. She uses a drawing of New York’s Guggenheim Museum, for example, to teach readers about the importance of using varied gray intensities to suggest depth and layering of interior spaces.

The Dictator’s Army: Battlefield Effectiveness in Authoritarian Regimes (Cornell University Press, 2015)

By Caitlin Talmadge, assistant professor of political science and international affairs

International relations theories have long tried to understand why states that ought to be more powerful militarily—they have the resources, demographics and technology—fail to outperform others. That they might sometimes impress and other times disappoint further complicates matters. In this book, Dr. Talmadge studies the questions through the lens of threats that face authoritarian regimes, and the degree to which the regimes need to respond.

A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars (University of Chicago Press, 2015)

By Andrew Hartman, MA ’03, PhD ’06

Many may associate “culture wars” with recent political rhetoric, but the question of what it means to be American is as old as the country itself. It’s a history that, while “often misremembered as merely one angry shouting match after another, offers insights into the genuine transformation to American political culture that happened during the sixties,” Dr. Hartman writes. Of course, the era hardly occurred in a vacuum. “But the sixties universalized fracture,” he writes, which made the period—in the famous words of writer Joseph Epstein—“something of a political Rorschach test.”