Bookshelves

Bookshelves

Alumnus Isaac Fitzgerald Writes About His Many Lives—From Altar Boy to Bartender and Author—in ‘Dirtbag, Massachusetts: A Confessional’

This “confessional” opens with a sentence Isaac Fitzgerald, B.A. ’05, has trotted out “almost like a joke throwaway line” at parties for years: “My parents were married when they had me, just to different people.”

Fitzgerald has lived many lives, some of his choosing. He was homeless and grew up around violence and alcohol and drug abuse. He was an altar boy, who left the church. Later, he rode a motorcycle, tended bar and worked for a time in pornography. “At a very young age, I knew that I wanted to say yes to things more than I wanted to say no to them. I just knew that would lead me to live an interesting life,” he told me in an interview. “That became a core tenet of my life.”

The memoir, in which Fitzgerald strives to tell the truth, paints a picture that is simultaneously beautiful, deftly observed and sad, and its closest relative—at least to me—is Frank McCourt’s “Angela’s Ashes.”

This is not the book that Fitzgerald thought he was going to write. It began as an essay collection about popular culture, told through the lens of his life. But after struggling for 18 months, he realized his life was the lead, not the supporting actor.

“I called my editor and said, ‘I think this might actually be a book about my childhood.’ A book that I had promised myself for many years I was not going to write,” he says. “She said, ‘Yeah. I’ve been waiting for you to understand that.’”

Many memoirists succumb to the temptation to always and only put their best feet forward but not so Fitzgerald, who goes hard on himself when he thinks he deserves it.

“You’re going to lose the reader’s trust, or even worse, the reader is going to get bored,” he says. “I really didn’t want any of the pieces in it to feel like they were these nice little presents wrapped up with a bow.”

When the author’s mother—who figures prominently in the beginning of the book—read the manuscript and asked him why he left out all of the happy times, like the family camping and canoeing trips, Fitzgerald turned to a metaphor of the truth as a log.“It’s a hunk of wood. I, of course, understand that you would carve a much different piece of art—a much different sculpture out of that hunk of wood than I would carve,” he told his mom. “This was my art. These are the moments I’m going to choose to highlight.” He was grateful that she understood immediately, Fitzgerald says.

For his father’s part, Fitzgerald writes in the book, “‘Are we going to be arrested for child abuse?’ my father asks me at one point, when we’re talking about my writing. He isn’t joking, but he isn’t not joking either. It’s his Irish way of asking, ‘How bad is this book going to be?’”

In writing the book, Fitzgerald drew upon his old journals and email. From his time in boarding school, he had an email account, and when Google launched Gmail in 2004, Fitzgerald got an early account. This meant he had a trove of easily searchable prior correspondence, with which he could cross-reference his memories.

He also asked permission to name people, and when he couldn’t secure it, changed names. He is very glad he could use the name of his first roommate in boarding school: Jon Ritzman. “What a great name for a kid from Cape Cod. It might as well be Jon Rich Man,” he says. When he couldn’t use a name, he struggled to make up ones that approximated the real ones.

“I have no imagination for that. Jon Ritzman was just the tip of the iceberg. I lost some beautiful names that I swear matched the personalities so, so well, and then I had to put in things like ‘Colin Smith,’” he says. He likes writing nonfiction—in which “I get to just see what happens and put it down on paper”—but he admires deeply “people who have the imagination to write fiction.”

For other writers, Fitzgerald cautions about the way a blank page can blind, and if one writes on the computer, all those red and green squiggly lines or auto-filling words can get in the way. “The machine is so ready to do the thinking,” he says, which is why he writes on paper, where he says his handwriting is so bad that he cannot get caught up in his mistakes. Like a gesture drawing, “I can just go, go, go,” he says. Later he transcribes his notes on the computer and corrects mistakes.

All the while, he wrote this book for himself at 14, or someone like he was then.

“In a way, I’m talking to a younger self. Because if there is one message in this book, I think it’s ‘Don’t deny the pain you’ve been in,’” he says. “I was trying to yell back through time at a younger self.”

– Menachem Wecker, M.A. ’09

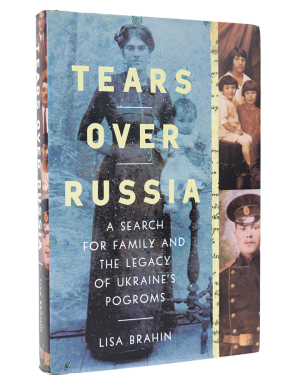

Tears Over Russia: A Search For Family and the Legacy of Ukraine’s Pogroms (Pegasus Books, 2022)

By Lisa Brahin, B.A. ’84

This book, which covers the years 1917 to 1921, explores a very different era in what was then Russia and is today Ukraine (now, of course, in the spotlight as Russia tries to take it back). The author’s grandmother, who told her stories at night as a means to get her to sleep, suffered from claustrophobia (elevators were traumatic) due to hiding in crawl spaces in the late 1910s. “The chaos that she survived shaped fears that haunted her for nearly 90 years,” writes the author, a Jewish genealogist. She notes that the time period she covers was a “prelude” to the Holocaust, and her grandmother “lived in a world that did not want Jews at all.” (Estimates range from 100,000 to 250,000 Jews killed in riots in what was then Russia.) “My curiosity only heightened when I discovered that there was almost nothing published about this time period,” the author writes. And so, “Tears Over Russia” was conceived. This is the kind of book one won’t want to put down, even as it could be written in blood as well as tears.

Mildred Trotter and the Invisible Histories of Physical and Forensic Anthropology (CRC Press, 2022)

By Emily K. Wilson, M.A. '08

The author, a forensic anthropologist, wrote this book partially as a biography of a trailblazing scientist—known for identifying remains of U.S. soldiers killed in World War II and for an infamous mistake measuring tibias—but also as a way to take stock of the scientific field at the time. Thus Mildred Trotter (1899-1991), who was the first woman to become a full Washington University School of Medicine professor and president of what is now the American Association of Biological Anthropologists, also becomes a lens through which to look at often ignored themes in science history, “such as scientific error, the historical experiences of women and marginalized people within the discipline, sexism, and scientific and social racism.” The book, which is rigorous and footnoted but also a very comfortable read, provides all sorts of fascinating tidbits along the way. For example, the subject and a colleague were the ones, in 1951, to first learn that people shrunk in size after reaching their maximum height. Of the tibia error, the author observes “a cautionary tale and a useful reminder that we are all fallible. Scientific research comes with a profound obligation to conduct careful, honest work.”

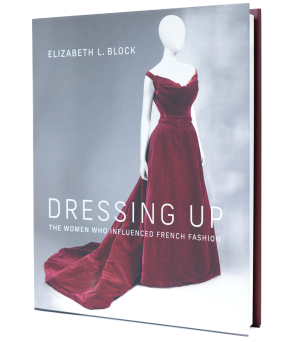

Dressing Up (MIT Press, 2021)

By Elizabeth L. Block, B.A. ’94

In this book, the author, who works in the publications department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, addresses the ways wealthy Americans in the 19th century participated in and influenced Parisian clothing design. At times, the relationship makes one’s head spin. “Curiously, many of the costumes were inspired by French royal figures who were ultimately ousted or killed,” the author writes, “an ironic association with the monarchy for wealthy U.S. citizens whose families became rich off of capitalistic ventures.” So did these American taste-makers know they were committing such a faux pas? That’s an open question, the author writes, “but we can access the paradoxes of some of their choices to give us a sense of the complexities surrounding them.” This book sorts through a great deal of complexity and enlists a host of relevant photographs and artwork along the way.

Hot Spot: A Doctor’s Diary from the Pandemic (Vanderbilt University Press, 2022)

By Alex Jahangir, B.S. ’99

– Menachem Wecker, MA ’09

Photography:

William Atkins