Baseball Island Dreams

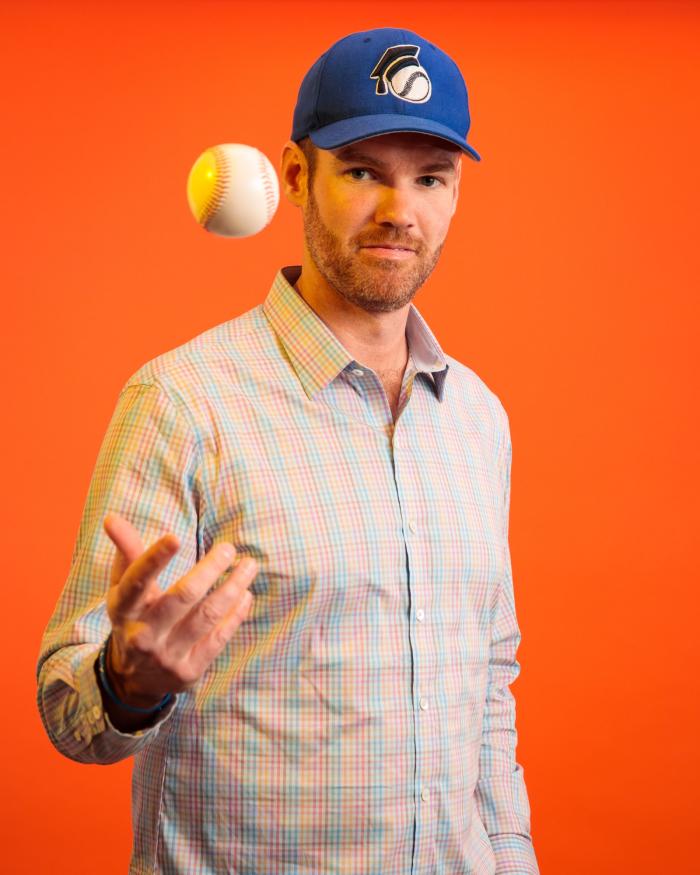

Derek Haese moved the Dominican Republic to coach the sport he played at GW. What started as a shot at fulfilling a dream, slowly became more. Now, after getting two pitchers signed with MLB organizations, Haese has founded an academy that’s about more

By Matthew Stoss

Four and one half years ago Derek Haese, a 36-year-old former GW baseball player, quit his white-collar job at a Washington, D.C., nonprofit to move to a Caribbean island and coach baseball in the sun.

“There was a meeting, and we were addressing an issue that had been addressed three or four years before,” says Haese, BBA ’07, an affable and rangy fellow. “With nonprofits you get turnover in leadership, and I think that day it hit me really hard that we’d already done this. It hit me like a ton of bricks: We’re just going to continue to do the same thing cyclically now in perpetuity?”

So in March of 2016, Haese, his wife, Susan, who is an elementary school teacher, and their two young children, Penelope and Cooper, moved to Las Terrenas, a lightly touristed town 1,400 miles from D.C. that juts off the Dominican Republic’s elysian northeast coast and is home to about 14,000 people.

There, Haese revived a dream that he long ago smothered with pragmatism: becoming a baseball coach. After raising hundreds of thousands of dollars back in America over the winter on the way to a $2 million goal, he founded the nonprofit Haese Academy which today occupies a repurposed eight-room hotel atop a verdant hump about a mile from the little town’s lone baseball field.

The academy exists primarily to help disadvantaged boys from the Dominican—where baseball has been hallowed for well more than a century—sign with Major League Baseball organizations or to play at U.S colleges. The academy, which opened in September, also has a corresponding school and community center.

“We were, financially, in a position where we could do it,” Haese says of the move. “We debated back and forth and decided to go for it. We said, ‘Why not? We only live once.’ If we don’t do it now we’ll look back in 30 years and say, ‘Man, what would it have been life if we went?’ So we sold all our belongings. I quit my job. We sold the house, packed six suitcases and flew the family down to this tiny fishing village.”

For decades MLB teams have run developmental academies for high school-age players in the Dominican Republic. The island nation of nearly 11 million is among the most baseball-prospect fertile places on this planet. It’s produced three Hall of Famers—pitchers Juan Marichal and Pedro Martinez and outfielder Vladimir Guerrero—and as of 2020’s pandemic-delayed opening day, the country claimed 110 players. That was 14.1 percent of all players on major league rosters.

Major league teams can sign players when they turn 16. The age is mandated by MLB to, in theory, discourage exploitation by its 30 franchises and by men known as “buscones.” The term comes from an antique Spanish verb that meant “thief,” sometimes invoked to reference pirates.

The buscones are prospect merchants. They clothe, feed, house, train and then peddle players to MLB teams. If the player signs—about only 5 percent of the thousands and thousands aspirants do every year—the buscones take a 30 to 40 percent cut of the players’ signing bonus as back pay for their services. This isn’t always lucrative, but it can be.

In 2018, the New York Yankees signed 16-year-old outfielder Jasson Rodriguez and gave him a record $5.1 million signing bonus, throwing 95 percent of their MLB-capped bonus money pool (and proportional amounts of hope) at one teenager.

That, however, is not the norm. Typically players sign for thousands of bonus dollars, not millions. Then the MLB teams remand the prospects to their academies for ripening. About only 1 percent of the hundreds of players signed ever year make it to the majors. Most finish their careers at 18, 19 or 20 years, once-shiny objects with the Dominican equivalent of a middle school education.

“The system down there is broken in a big way,” says Jay Quinn, BA ’06, a former GW player and assistant coach at Columbia who has worked extensively in international baseball. “It’s great that there are a lot of Dominican-born players in Major League Baseball doing well, making money, coming home, giving back, but for the majority that’s not their story. The vast, vast majority of these kids drop out of school at 11, 12 years old. Even if they do end up getting signed, it’s the [buscones who] are successful. Everybody walks away from the kids once they sign the contracts, and the kids end up blowing their money, never really getting an education, and then they’re back where they started.”

Haese already has guided to players to contracts with major league organizations. He took then-teens, hard-throwing right-handed pitchers Yoelvin Silven and Jonathan Almonte, into his home, adopting them in every sense but the legal ones. (The Haese have done this for several kids, including Junior Ventura, the younger brother of former Kansas City Royals star pitcher Yordano Ventura, who died in a car wreck in 2017.) Haese, a former pitcher, coached them, and Susan, tutored them. Then early in 2018, Silven signed with the Chicago White Sox. Almonte signed with the Arizona Diamondbacks a day year. Silven got invited to major league spring training this year.

Off that, and overwhelmed and moved by the third-world plights of so many of the young players, the Haeses decided to open the academy. Its niche in the crowded, sometimes slimy prospect market, where the buscones and countless other academies proliferate, is education. Haese is preparing players not only for a shot at an alternative baseball career on one of the thousands of U.S. college teams if MLB doesn’t ask them to dance, but for a future.

“What’s cool about the academy is it’s a new model,” Quinn says. “I haven’t seen anything like it—and it’s not just baseball and it’s not just teenagers. It’s building a community center, classes for adults, a co-ed school for children and just making sure that it’s almost what you get at a USA high school where you have to hit a certain grade in the classroom, or at least be in tutoring if you’re struggling—really showing improvement, showing effort in the classroom, earning your time on the baseball field.”

Dominican baseball is a robust and ruthless industry, and Haese is adamantly not a buscone. Yes, he’s going to help kids play baseball and take a small percentage (15 percent) if they sign. That’s to help keep the academy/school/community center solvent, but the purpose of all this isn’t to open another stall in the meat market.

Derek and Susan Haese want to give these kids a chance at a good life when pro baseball almost inevitably doesn’t.

“We use the sport as the vehicle,” Derek Haese says, “but the sport is not the goal. The education is a goal. However, telling a 16-year-old fighting for his life in an environment stricken by extreme poverty that education is the most important thing is a pretty tough sell. It’s, ‘Yeah, whatever,’ right? But if I tell them them, ‘Look, if you’re really good, learn English and do well in school, you can go play college baseball in the States and have a chance to get drafted,’ they might stay more interested in their education—hopefully.”

Las Terrenas is rather fetching. There are palmetto trees that shimmy in the wind along wish-you-were beaches. Inland through a hedge of hotels are serried rows of pastel buildings, their balconies enclosed by curly wrought-iron gates de-blacked by saline breezes along a figure-eight of a main road.

The people are amiable—tranquilo is their ethos—but wary of strangers after so many centuries of colonial intrusion. They ride motorcycles and ATVs work the hotels, shops and restaurants. The shoreside villas and resorts are largely for the well-to-do expatriates and snowbirds, so the locals keep to the city and its outskirts where the smell of empanadas gives out to that of burning trash and the penury of tin-roofed shacks too hot to abide in direct daylight.

Luxury festoons the coast. There the outlanders reinforce the Dominican’s modest but growing economy and lounge away the sunsets. The expats are mostly Canadian, French and Italian. There aren’t many Americans. They keep to Punta Cana, the Dominican equivalent of Cancún 180 miles to the southeast. Las Terrenas is more hideaway than getaway, at the least the coast.

Tourist and expat spending, at least before COVID-19, strengthened the Dominican economy. It averaged 5.3 percent growth between 1993 and 2018, according to the World Bank. That’s among the highest rates in the Latin America/Caribbean region. The Dominican’s 6.3 percent average from 2014 to 2018 was tops in that region.

The Dominican Republic’s gross domestic product in 2019 was $88.9 billion (the United States’ was $21.3 trillion), but despite more upward mobility and a nascent middle class it remains a poor country, albeit a politically stable one, unlike, say, Venezuela, where Major League Baseball has closed the academies it started opening in the 1990s. That makes the Dominican all the more alluring. So does its baseball pedigree.

Cubans fleeing the Ten Years War and Spanish colonialism brought the sport to the island in the 1870s. The United States also occupied the Dominican Republic from 1916 to 1924 and again the 1960s, further undergirding baseball’s popularity.

It spread in a handmade way, bolstered by major leaguers barnstorming through the Dominican to make offseason money before the days when hitting a ball with a wooden stick could buy a guy a mansion. By the mid-20th century, baseball rated as a pastime. Kids made their own equipment and played wherever they found space while sugarcane companies sponsored local teams.

Dominicans reached Major League Baseball nine years after Jackie Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers, becoming in 1947 the first Black player to appear in an MLB game since 1889 and stoically immolating the gentleman’s agreement between the owners that banned African Americans.

Robinson’s debut made it possible for dark-skinned Latin players, previously confined to the Negro Leagues—its players also barnstormed through the Caribbean, notably Cuba—to play Major League Baseball.

Ozzie Virgil became the first Dominican major leaguer when he started at third base for the New York Giants on Sept. 23, 1956. From there, Dominican talent spread through MLB, eventually necessitating and fueling the academy system. The Los Angeles Dodgers opened the first one—Campos Las Palmas in San Antonio Guerra, about 25 miles east of Santo Domingo, the Dominican capital—and today Latin culture flourishes.

“There’s a certain flair and style that they’ve brought,” says Rob Ruck, a professor of sport history at the University of Pittsburgh and the author of Tropic of Baseball, a history of the sport in the Dominican Republic, and Raceball, a history of non-White players in MLB. “Some of the more conservative traditionalists might say they’re hot-dogging it, but it’s their style of fielding, running—just the exuberance. I think the traditional ballplayer, pre-immigration, was sort of the tobacco-spitting, taciturn guy who wasn’t very colorful—look at the hairdos on the Astros from a couple of years ago when they won [the World Series]. They bring a different culture to the game, and I think that’s been incredibly important for baseball which has lagged in diversity.”

Mickey Shupin, BA ’06, MTA ’08, has worked at Major League Baseball for 12 years, and all MLB’s international business runs through Shupin’s office which arranges the World Baseball Classic. It’s the sport’s equivalent of the World Cup.

Shupin, who played baseball at GW and helped broker an audience at MLB headquarters for his college teammate Derek Haese, says that Major League Baseball is trying to emphasize its international seasoning and better recognize the Latin American market. Pre-coronavirus, the 2020 schedule featured regular-season games in Puerto Rico and Mexico.

Shupin describes Latin American baseball games as a “party for nine innings” and contrasted the carnival atmosphere there to the subdued mien of a game in America. Here, the sport is shambling to regain its once-grand relevance. Baseball never lost it in the Dominican, where, despite a steady economy, the poverty and a lack of education define a hunk of the population and make baseball equal parts life and death.

Eighty percent of Dominican kids in low-income brackets drop out of school before ninth grade, says one University of Texas study. The median income is about $4,700 a year. For the blessed few, baseball is a golden ticket off their 18,653-square miles of Hispaniola.

Ruck was there the day the Dodgers opened their academy near Santo Domingo. It’s the one that produced Hall of Fame pitcher Pedro Martinez. Ruck says that Juan Marichal popped in. The facility had clean, mosquito-free dorms, hot water, barbered fields, three meals a day, medical care and of course MLB-level baseball instruction. (Academic education, at the time, not so much.)

A few years later, Ruck, back in the Dominican once more, met a local woman whose son had just got a tryout.

“She said, ‘Well, you know he’s going to eat for 30 days.’”

Derek Haese grew up in New Jersey before his parents’ divorce rearranged his geography, and he ended up in high school in Colorado. A growth spurt at 17 made him a foot taller and nudged his fastball up to around 85 miles per hour, pretty fast for a high school kid.

After a layover at Division III California-San Diego, Haese landed at D-I GW where he grew into his 6-foot-6-inch body, and his fastball eased into the low 90s. He had his best season his junior year, going 6-4 with a 2.09 ERA in a team-most 24 appearances, and following a short, short stint in an independent league and thinking more with his bank account than his heart, he took a job at the aforementioned Washington, D.C., nonprofit where he regulated and licensed architects after a torn labrum in his right shoulder took his baseball career as collateral damage.

Years later he buried his white-collar career alongside it. It was 7 years old and had been in declining health for some years.

“I always wanted to be a coach,” Haese says. “We were at a place where the money was great but our lives were not, and I wasn’t totally fulfilled. A big piece of me was fulfilled, but it was, ‘All right, if this what I’m going to do with my life, then am I really making difference?’ It was providing for my family but it wasn’t satisfying.”

In March 2016, the Haeses emigrated from the suburbs of Reston, Va., to the palmy outpost of Las Terrenas so Derek could start what he calls his “coaching internship.” Susan, fluent in Spanish thanks her attending a Spanish-immersion charter school in D.C. while growing up, got a job teaching at the Las Terrenas International School to give the family an income.

At the local baseball field Haese introduced himself to the “field boss,” a good guy buscone (they exist) who coached Yordano Ventura. In the Dominican Republic, field bosses are paid by the local government to maintain, surprise, the town baseball fields.

Haese says he thinks the boss accepted him because sometimes tall can seem authoritative. In this instance, essentially, Haese, at 6-6, just looked like a baseball player. He didn’t yet speak Spanish, so he got by with pantomime. By mid-September, he got to run a practice.

Haese opened the morning with conditioning, tasking the 12 or so teenage players with running 10 sprints from foul pole to foul pole. He gave them one minute to finish each sprint.

“After the first roundtrip,” Haese says, “they came back and they were looking rough, and I thought, Yikes, we only did two.”

That’s when a bystander intervened. He told Haese that the kids couldn’t do this. Haese didn’t understand.

“If they want to play professional baseball,” Haese told the local man, “this is nothing. They’re going to have to do this.”

Haese told the kids to go again.

“They all run back, and at this point, they look like they’re going to pass out,” Haese says. “Clearly, it’s hot down there, so that’s one factor. But it was four pole sprints. So the guy says again, ‘You can’t do this.’ I said I don’t understand. He said, ‘You literally can’t.’ Watch.’”

The man turned to the kids heaving in the sunburnt grass.

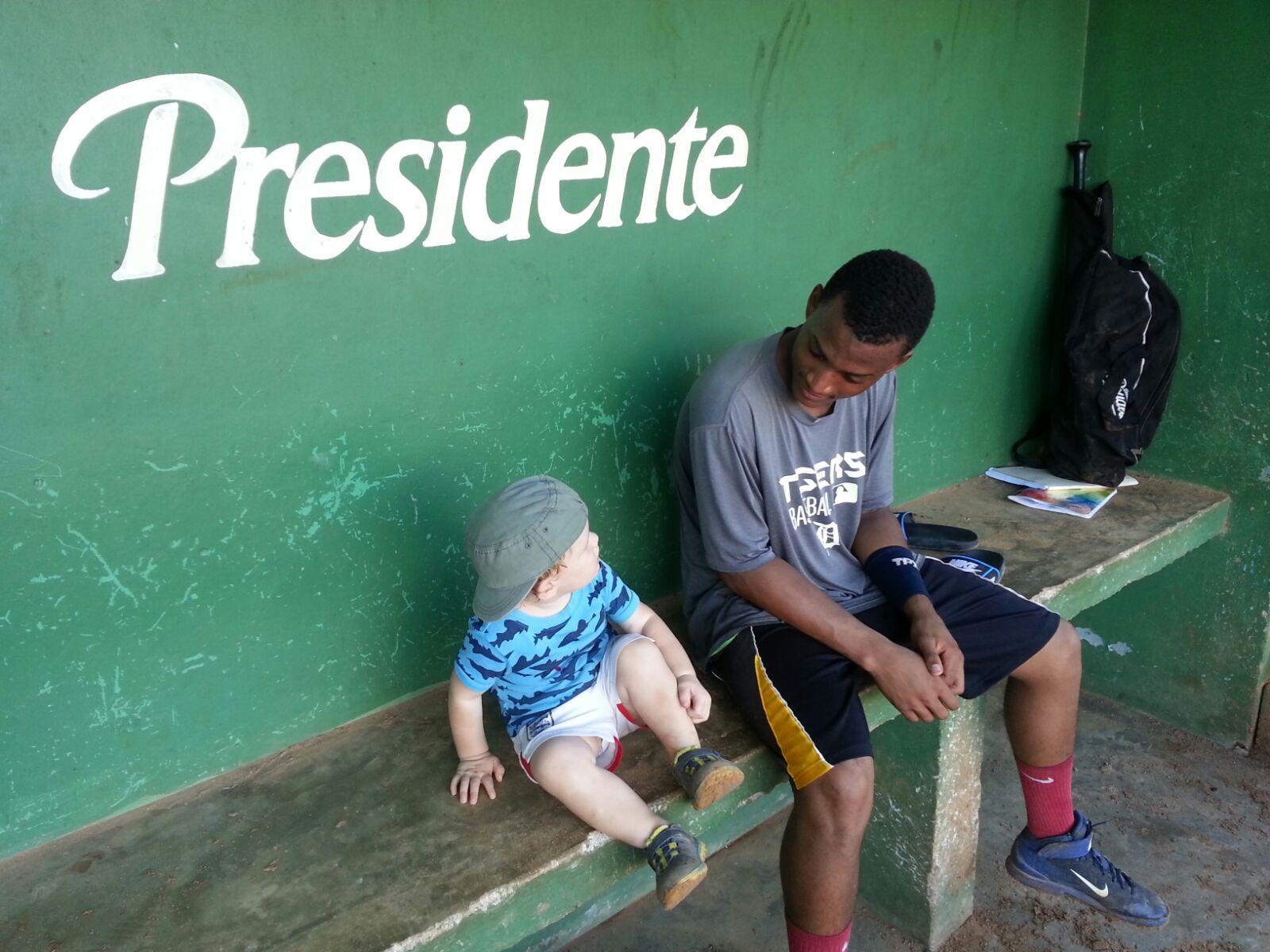

“Time out, guys,” the man said. “How many of you had dinner last night?” About three kids raised their hands. “How many of you had breakfast this morning.” Again, two or three kids raised their hands. “See,” the man said, turning to Haese. “They literally can’t do it. They have no fuel.”

Haese took a photo of the kids resting their lungs in some commandeered shade four sprints into a three-hour practice.

“It’s just this random picture of some kids sitting down,” Haese says, “but it symbolized the moment in my life I realized the game down there is different. We play baseball for fun, but for them, it’s their life. It was eye-opening. This is real and this is serious and it’s not a game. It changed my life.

“So I picked my kids up from school, went home to my wife, and I was like, these kids aren’t eating. They’re not drinking water. They’re not in school. They’re all trying to sign these professional contracts but there’s no way they’re going to be able to do that. It’s just an epic failure on so many levels.”

Conditions in the Dominican Republic enable the buscones. Poverty is pervasive, employment options do not abound and education can be hit or miss. For the baseball-dreaming youths, this can make the sport a career before high school, even though it doesn’t pay and probably won’t.

Not all buscones are conmen, as Derek Haese’s field boss proves—like many Dominicans, they, too, are limited by circumstances—but they’re so entangled in the demimonde of Dominican Republic baseball that they’re practically symbiotes.

“It’s an effort to use baseball to help somebody have a better life,” says Rob Ruck, the University of Pittsburgh professor who’s written about Dominican baseball. “But you’ve got on the other end those who are still giving kids veterinary steroids.”

He’s not kidding.

Neither the Dominican government nor Major League Baseball regulate the buscones. That means any schlub can profess baseball expertise, woo a prospect and start trying to cash in. Hence the animal steroids administered by men unburdened by medical knowledge.

MLB has improved its academies in recent years, offering proper academic educations to supplement the baseball instruction, pushed to do so by the Dominican government and activists. There also has been pressure internally at MLB. Now almost every academy mandates schooling, too. The academies teach English, trades and offer avenues to high school diplomas.

“These kids quit school at early ages, 13, 14, to train and focus on baseball,” says Jeff Diskin, the Kansas City Royals’ director of player development. He oversees the team’s educational programs for Latin recruits. “But it’s not all that uncommon in third-world countries for kids to quit school at the time they become an age where they can start providing for their families. It’s hard. I mean, you’ve got to change your lens and how you see it.”

Diskin says the reforms came out of the abuse accusations.

“Whether or not they’re exploited is up for debate,” he says. “But in the eyes of many people, it was: You are exploiting a Latin player. But I think clubs have found out that the more educated your players are, that increases the likelihood of them reaching their ceilings. If you can teach them English, where they can understand instruction—if you can ensure that they get their high school diploma, which increases their ability to reason and to think critically—all that helps them develop.”

Diskin met Haese in 2017 while the Royals were renovating the Las Terrenas baseball field in memory of Yordano Ventura. The best player to come out of Las Terrenas, Venutra died in a single-car wreck on Jan. 22, 2017. He had signed a five-year, $23-million contract a year and a half earlier after the Royals plucked him for $20,000 off the dirt infield of his hometown field. His grave is just a little ways from the shore. He was 25 years old.

“At 3 in the morning, he flipped his Jeep, and that was it,” Haese says. He never met Yordano. “Twenty-five years old, all-star, whole life and career ahead of him. But he had no mentor, management guide, anybody, and he just did what many in that situation would do. All of sudden, this kid with no education—he’s 23 when he really came into his money—receives millions of dollars. What does the guy do? He buys like seven cars, sports cars in the States, sports cars down there, a jacked-up Jeep down there. Partying, wrong crowd.

“Keeping kids from making the same mistakes is one of the pillars of my academy.”

Haese stresses education over baseball at his academy—where Yordano’s younger brother Junior, a one-time pitching prospect himself, is an instructor—and that U.S. college ball can be an alternative in the likely event of a major league spurning. That’s contingent on players getting good grades, graduating and learning English. It’s a strategy that’s already worked. Haese and his team already have sent a player to Miami-Dade, a junior college in South Florida with a baseball pedigree. Hall of Fame catcher Mike Piazza is an alum.

Some college coaches have prospected in the Dominican Republic, but that pipeline remains largely shut because a lot of Dominican kids can’t get into an American university. The reason is a lack of schooling.

Pro baseball obviously is the goal, but college baseball is still baseball—and it can offer a second shot at the major leagues. About 25 percent of players taken in the MLB draft every year are high schoolers. If a player goes unpicked, he’s eligible again after three years in college or when he turns 21. There’s also free agency if he goes undrafted after his senior year in college.

“That’s really where the rub is and why we’re unique,” Haese says. “This meeting with MLB, they looked at us and said, ‘You sound like a buscone.’ I said, ‘No, we’re there for the education. We’re here to solve problems.’ It’s hard to sit there and tell someone who knows the market down there, ‘No, no, I’m doing this for the right reasons; you need to believe me.’ Because they don’t.”

Diskin first encountered Haese when he went to the field one day and noticed a 6-6 white guy. They introduced themselves and hit it off. Haese later helped with the field which today boasts cement bleachers, dugouts and an electronic scoreboard. Now Diskin acts as an informal adviser to Haese.

“He wants to give back to the underprivileged,” Diskin says. “I think everything is very genuine. For me, in the Dominican Republic, it’s hard to know who to trust. I don’t want this to come across wrong, but it seems like you’re always waiting for that twist or something. You know [the buscones] want something. There’s an angle. There’s a material motive. For Derek, it’s about giving back and making the community a better place.”

To start, the Haese Academy school has two classes: kindergarten and third grade. They’re picked to correspond with the Haeses’ kids, 7-year-old Penelope and 5-year-old Cooper and their local Dominican and Haitian friends. More classes will be added as the Haese kids advance and as the school establishes itself in the town which has eight public schools—often stuffing as many as 40 kids into one classroom—and two private schools. The latter costs between $200 and $250 a month and largely caters to the expat families.

The Haeses’ school costs $150 but is free to those who can’t afford tuition. Right now the faculty consists of Susan and a local teacher with whom Susan taught at the Las Terrenas International School. Lessons will be taught in Spanish and English.

The Haese school, once the hotel repurposing is done, will offer meals, a computer lab, supplies and a community center. The Haeses, again, are looking to raise $2 million.

“Some people look at the money that we say we need and say, ‘God, why so much?’” Haese says. “Our response to that is they deserve it to be done well. They deserve access to quality materials and comfortable spaces—classrooms with air conditioners. It takes a plan and it takes money. It’s not like, ‘Oh, they’re so dirt poor, they don’t need that. Anything is better than nothing.’ That’s just not how we’re doing things.”

On the baseball academy side, the older players practice in the morning with Haese, then spend afternoons with tutors before going to night classes in town en route to the Dominican equivalent of a general-equivalency degree. That’s what Jonathan Almonte and Yoelvin Silven, both taught by Susan, did before signing with the Diamondbacks and White Sox, respectively.

“He’s done that from the purest of intentions—wanting his children to see that there’s another side of life, at such an early age,” Diskin says of Haese. “And then to see his children interact with the Dominican kids—it’s beautiful. And he encourages it and he wants that. So many Americans think that the United States is the center of the world, and that the rest of the world revolves around us, and he understands that the world’s a bigger place in that. He understands people are people, and he has this ability to pour into others and invest in others his own time and resources and energy.”

The Haeses had been in the Dominican Republic for seven months. Derek had gotten to know the town, the people, the players. He’d even got himself an ATV so he could makes his way around the Las Terrenas figure-eight like a local.

Then one day after a practice Haese started chatting with a local guy who had moved to Pennsylvania to be a truck driver. He was back home visiting.

“We were talking,” Haese says, “and he says, ‘Oh, have you seen the house?’ And I said no. He says, ‘Come with me. This is the not-fun part.’”

The house belonged to the field boss, who doesn’t make a lot of money but does the best he can. It wasn’t far from the ballpark, off in the dirt amid the foliage. Haese hadn’t considered it much. He thought it was a garage.

“I walked in and I was like, oh my god. Tin roof, cement floor—which I learned later was an upgrade. There was a living room that had a gigantic pot that they were cooking in. It was a coal stove, I’d guess you’d call it. I don’t even know what it was.

“There was a bathroom in between two bedrooms, and around the back there was another big space. There were four mattresses on the floor in one room and three in the other and about eight in the back—and all the mattresses looked like he got them out of a dumpster in the Bronx in 1980.

“The place smelled horrible. There was indoor plumbing but it was not something you’d want to touch. It was brutal. I actually went back over there and took a picture of it because I just couldn’t believe that anyone could live like that. Unfortunately, or fortunately, I’m not sure, my kid threw my phone in the toilet very soon thereafter, and I lost the picture.”

Haese’s memory was plenty.

“Shortly thereafter there was a flood,” he says. “It was at the end of October 2016. So right after I started working there with the boys. It flooded the house and it gave me the opportunity to insert myself.”

The field boss showed up at the field crying after the flood. He said everything they had was ruined.

“I couldn’t stomach that he had these teenage boys living away from home in this slum,” Haese says. “So I pulled 600 bucks out of the ATM, and I went and bought four king beds and a couple of twin mattresses. I had to make up this story, too, because I didn’t want them thinking that I paid for it. It was just so awful. I vividly remember thinking: I have this money in my account, and they need it so much more than I will ever need it. So I bought them all new mattresses. I then went home to my wife and said we have to do something.”