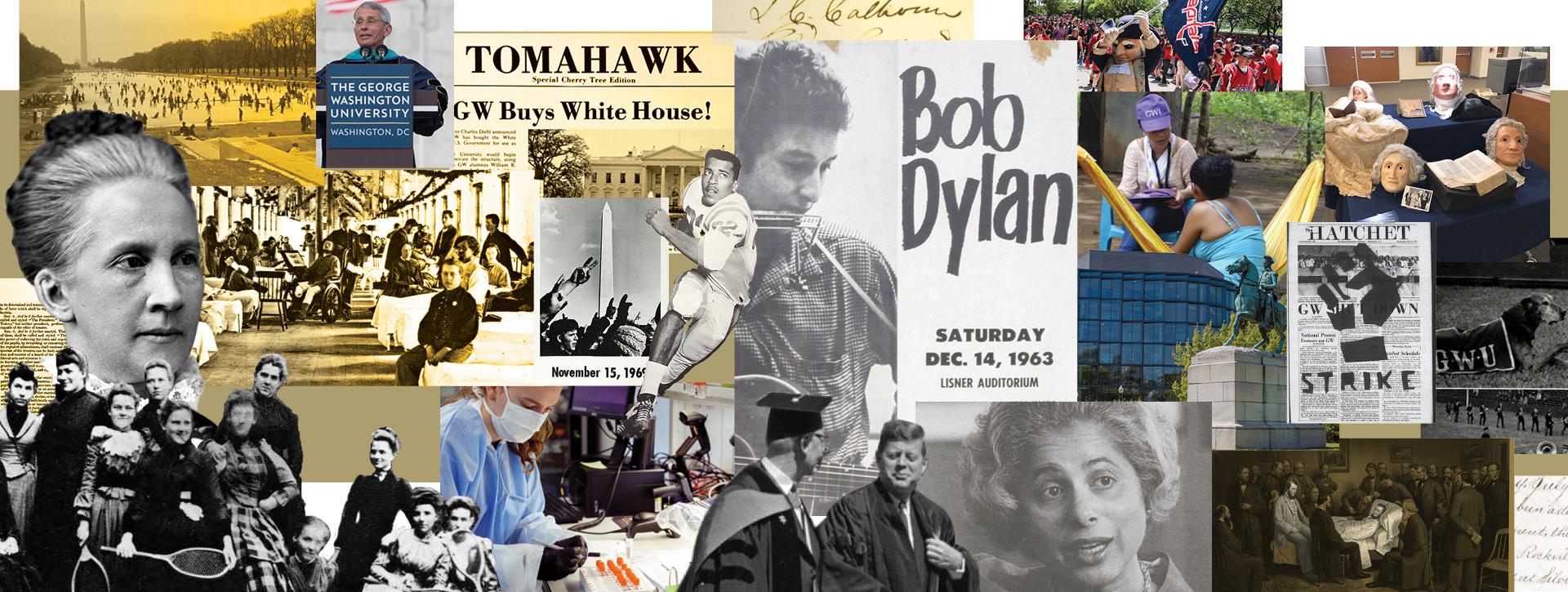

200 Facts & Artifacts

200 Facts & Artifacts

A deep dive into GW’s archives to showcase the university’s rich history, from its presidential origins to its vibrant present.

By Ruth Steinhardt

What does Ingrid Bergman have in common with Walt Whitman, a horse named Nelson and the developer of the big bang theory? They’ve all played a part in the George Washington University’s 200-year history. Below, drawn from the GW Archives and Gelman Library’s Special Collections, are those and 197 more stories and images from two centuries of GW.

The Beginning

1. When George Washington died in 1799, his will directed that 50 shares in the Potomac Company, an organization devoted to improving navigation on the Potomac River, be used to support a university in the District of Columbia.

2. The clause from Washington’s will that started GW’s journey read, “I give and bequeath in perpetuity the fifty shares which I hold in the Potomac Company…towards the endowment of a university to be established within the limits of the District of Columbia.”

3. A university established near the seat of government was a long-held goal for Washington. He wrote to aide and editor Alexander Hamilton in 1796, “That which would render it of the highest importance, in my opinion, is young men from different parts of the United States would be assembled together, & would by degrees discover that there was not that cause for those jealousies & prejudices which one part of the union had imbibed agains[t] another part.”

4. In 1819, four Baptist ministers—Luther Rice, Obadiah B. Brown, Spencer H. Cone and Enoch Reynolds—raised the needed funds to purchase land in the nation’s capital, petitioned Congress for a charter and began organizing a college.

5. One appeal for funding for the buildings of the proposed college was signed by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, among others.

6. In 1820, 47 acres of land were purchased for the new college on College Hill, just north of what is now Florida Avenue between 14th and 15th streets.

7. Among the initial subscribers were President James Monroe and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who each donated $50—the equivalent of about $1,100 in 2021.

8. On Feb. 9, 1821, President Monroe signed the Act of Congress that created the college.

9. In 1827, the college went into a financial crisis so severe that it was forced to suspend classes for several months.

10. It reopened for a three-month summer term in 1828, after Congress agreed to cancel about $30,000 of its debt in exchange for some college property, and it resumed a regular semester cycle in September.

11. Columbian College was officially a nonsectarian school but had an unofficial Baptist affiliation that would last until the denomination split over the question of slavery in the mid-19th century.

12. By Act of Congress, the school changed its name from Columbian College to Columbian University in 1873 to reflect its broadening educational aspirations.

13. In 1904, Congress approved a name change from Columbian University to the George Washington University at the prompting of the George Washington Memorial Association.

The Earliest Student Experience

14. The university’s College Hill location was at the time outside the limits of Washington, D.C., about half an hour’s walk from the U.S. Capitol. Students needed faculty members’ permission to go into the city.

15. To be admitted, students had to be white, male, acquainted with English grammar and arithmetic, knowledgeable in geography and able to read, write and translate Latin.

16. Latin was not dropped from official B.A. requirements until 1908.

17. Tuition in 1821 was $30 for the first semester and $20 for the second. A load of laundry—defined as 12 items—cost 37 cents.

18. A student account from 1825.

19. Columbian College’s first department was theology, established by Professor Irah Chase with 11 students.

20. In 1822, the college added a Classical Department, and enrollment grew to 30 students. Admissions standards required that applicants “produce satisfactory evidence of a good moral character.”

21. The graduating class of 1824, Columbian College’s first, comprised just three students. The visiting Marquis de Lafayette was the guest of honor at this very small commencement ceremony, which included speeches by all three graduates and by several sophomore and junior students. Topics included “Responsibilities of American Youth” and “The Superiority of Grecian over Roman Literature.”

22. Today, more than 27,000 students hailing from every state and more than 130 countries worldwide call GW home.

23. In 1847, 27 graduates formed the Alumni Association of Columbian College. GW alumni now number more than 300,000 worldwide.

24. Requirements for student behavior at the college’s inception were stringent. In 1822, students could be punished for any number of small vices, including throwing stones within a hundred yards of any building or using a musical instrument on the Sabbath.

25. Faculty members maintained a merit book in which conduct records of the students were kept. They visited the rooms of the students frequently, and all cases of insubordination, delinquency and breach of college laws were reported.

26. The students seem to have responded well to this strict discipline. In 1848, the Washington News said of Columbian College students, “We have heard of no outbreaks among them nor sprees, nor skylarking, which are ever and anon occurring in other similar institutions… We venture to assert that none of the last year’s class was ever seen in any improper place, or indulging in any unbecoming deportment.”

A Changing Campus

27. The original campus consisted of five brick buildings: a main college building, which had five floors, 58 rooms and 60 fireplaces and could accommodate 100 students; three other buildings occupied by the president and his family, the faculty and a steward; and a building used for classrooms.

28. The original college building.

29. Electric lights were installed on the first floor of the University Building in 1891, and the university treasurer authorized installation of a telephone a year later. Now, GW is committed to reducing its carbon footprint through energy-efficiency initiatives and clean-energy purchases, including getting half of its energy from three solar farms in North Carolina.

30. The Medical Department began classes in anatomy, surgery and obstetrics in 1825, and, in 1826, constructed a “large and commodious” building at 10th and E streets, NW. It would later move to H Street, NW. Students were allowed to observe and even to perform operations.

31. The Columbian College Medical School building on H Street, 1896.

32. 1826 also marked the establishment of the first iteration of GW Law. Although then-President John Quincy Adams attended the opening lecture by U.S. Circuit Court Judge William Cranch, the school closed just two years later for financial reasons. It would be revived in 1865.

33. William Cranch, the first professor in the Columbian College law department

34. In 1844, Congress granted the college use of a building at Judiciary Square as an infirmary. This became the first general hospital in the District of Columbia and one of the nation’s first teaching hospitals. The infirmary would burn down in 1861, six months into the Civil War.

35. In 1852, faculty urged the college to create a new department distinct from the Classical Department, combining studies in English, mathematics, science and engineering.

36. The university moved in 1884 to downtown Washington, where it built two buildings at H and 15th streets, NW. These were sold in 1910, and Columbian occupied rental space on I Street, NW, until moving permanently to Foggy Bottom in 1912.

37. At the time, Foggy Bottom was an industrial neighborhood full of warehouses, coal yards and breweries.

38. Washington Circle, where the George Washington University Hospital now stands, was known in the early 20th century as “Round Tops,” partly for the cupola roofs on some nearby buildings and partly in reference to the notorious Irish gang that controlled the neighborhood.

39. Exploration Hall, the first building on GW’s Virginia Science and Technology Campus, opened to students in 1991. The campus has since expanded to 122 acres.

A Changing Student Body

40. The medical school admitted its first four women in 1884, but soon decided that allowing men and women to work together was “a strain on modesty.” It would not admit women again until 1911, and then only through the nursing program.

41. Clara Bliss Hinds was the first woman to receive an M.D. from Columbian in 1887.

42. Mabel Nelson Thurston became the college’s first female undergraduate student in 1888. Thurston Hall is named in her honor.

43. Eleven other women were admitted as undergraduates in Thurston’s second year, while one woman was admitted to the scientific school. These were collectively referred to as the “original 13.”

44. Belva Ann Lockwood, the first woman to run for president and the first to practice law before the U.S. Supreme Court, received her degree from the National Law Center—later merged with GW Law—in 1873.

45. Samuel Laing Williams was the first Black student to graduate from the college, receiving his J.D. in 1884.

46. The GW Menorah Society was founded in 1916 and, during the early 20th century, was a center of Jewish life on campus. Its spiritual successor, GW Hillel, was formed in the 1930s and now serves more than 4,500 undergraduate and graduate students.

47. In 1964, Ruth Osborn created “Developing New Horizons for Women” at the GW College of General Studies, starting with a noncredit orientation class of 20 women. The course would become a blueprint for women’s continuing education in the 1960s and ’70s.

48. Patricia Roberts Harris graduated first in her class from GW Law in 1960. She went on to make history as the first Black female dean of Howard University’s School of Law, the first Black woman named an American ambassador and—after her confirmation as secretary of housing and urban development in 1977—the first Black woman to enter the presidential line of succession.

49. GW is now home to the Global Women’s Institute, a multidisciplinary research and policy institute dedicated to advancing the rights and interests of women and girls. GWI has partnered with universities and organizations worldwide on issues of education, financial emancipation, domestic violence reduction and more, including a recent study that found violence against women and girls is preventable.

The College and the Civil War

50. Until 1863, slavery was legal in the District of Columbia. While there’s no evidence that Columbian College itself held slaves, some of its employees did. In 1847, student Henry J. Arnold provided an enslaved man named Abram with $14 and a letter for an attorney, intending to help Abram sue for his freedom from the college’s steward. Arnold was expelled; Abram and another man who had also planned to escape were sent back to Virginia.

51. Most students left their classrooms to fight when the Civil War began. Forty-six of the school's medical graduates served in the Union Army and 24 in the Confederate Army.

52. A letter from a group of students, presumably Confederate sympathizers, suggested that GW’s reputation in the South was that of a school “of a Northern Character and conducted by a faculty holding Northern principles.”

53. Like the students, the faculty was split by opposing loyalties. Professor of Anatomy A.Y.P. Garnett departed to serve as physician to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, while professor and physician Robert King Stone remained to become the personal physician to Abraham Lincoln.

54. Because so many students and faculty members were at war, and since most of the campus had been seized for Union use as a military hospital and barracks, many of the professors who remained taught out of their homes for the duration of the conflict.

55. The hospital treated at least one distinguished civilian: first lady Mary Todd Lincoln, who was thrown from a carriage outside the college entrance on 14th Street. Mrs. Lincoln got along so well with her nurse, war widow Rebecca Pomroy, that she afterward regularly called Pomroy in for other illnesses in the Lincoln family.

56. Poet Walt Whitman was among those who helped nurse wounded soldiers at the Columbian College and Carver General hospitals on campus.

57. On June 3, 1864, Whitman wrote to his mother, “I [gave] in Carver hospital a great treat of Ice Cream, a couple of days ago, went around myself through about fifteen large wards—I bought some ten gallons, very nice…Many of the men had to be fed; several of them I saw cannot probably live, yet they quite enjoyed it…..[Q]uite a number [of] Western country boys had never tasted ice cream before.”

58. Hospital tents with the Columbian College building in the background

59. Gelman Library’s Special Collections include the diaries of alumnus and Washington Post cartoonist George Yost Coffin. On July 11, 1864, the then-teenage Coffin recorded rumors that the Confederate Army was gathering in what is now suburban Maryland: “the Confederates are between Rockville and Tennalytown & are reported at Silver Spring.”

60. Columbian Professors John F. May and Albert Freeman Africanus King attended the bedside of the dying President Lincoln when he was assassinated in April 1865.

Schools Come, Go and Stay

61. After the war, an expanded federal bureaucracy and influx of government employees into the area created a need for part-time and continuing educational options. Over the following years and decades, Columbian would expand accordingly.

62. What is now GW’s Mount Vernon campus was founded in 1875 as the Mount Vernon Seminary and College, the first higher education institution for women in the District of Columbia.

63. Mount Vernon became part of GW in 1999.

64. In 1857, Congress chartered a school for children unable to hear or speak, which would later merge with the Columbian Institution for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind led by Edward Gallaudet.

65. Columbian College established a school of dentistry in 1887. The dental school would share facilities with the medical school until 1920, when it was discontinued.

66. An alarming introduction page for the dental school from the 1913 Cherry Tree yearbook.

67. In 1898, Columbian established a School of Comparative Jurisprudence and Diplomacy. This was replaced in 1905 by the School of Politics and Diplomacy, the forerunner to the Elliott School of International Affairs.

68. GW merged with the National Veterinary School from 1896 to 1898, then re-formed its own veterinary college from 1908 until 1921.

69. The GW School of Public Health and Health Services was established in 1997 and remains the only school of public health in the nation’s capital. In 2014, the Milken Institute, the Milken Family Foundation and Sumner Redstone Charitable Foundation donated a combined $80 million to the school, establishing the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness at the renamed Milken Institute School of Public Health.

In the Heart of the City

70. Columbian University celebrated its first name change in 1874 with a gala celebration at Wormley’s Hotel, an internationally famous D.C. establishment owned by former jockey and steward James Wormley. Wormley was a revered Black businessman who owned multiple hotels and homes and even a racetrack in what is now Tenleytown. He was an abolitionist and a confidant of the D.C. elite, including Frederick Douglass and Charles Sumner. When he died in 1884, many of Washington’s hotels flew their flags at half-mast in salute.

71. Bob Dylan played a show at Lisner Auditorium in 1963. Flyers from the performance are now a valuable collector’s item.

72. Since 1980, GW has partnered with its neighboring School Without Walls—a nontraditional high school that models the “community as a classroom”—to provide educational opportunities for students at both institutions.

73. In 1989, then-GW President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg launched the 21st Century Scholarship, an annual award covering the entire cost of four years of tuition, room and board, books and fees for incoming undergraduate students from the District of Columbia. Now known as the Stephen Joel Trachtenberg (SJT) Scholarship, the award has been given to about 200 D.C. students.

74. GW is the only university to celebrate its commencement on the National Mall (in non-pandemic times).

75. GW's students and faculty have access and proximity to influential institutions that span the Washington region, including Capitol Hill, the White House, NIH, Smithsonian and World Bank.

76. Costumed GW representatives were in attendance when the Foggy Bottom Metro station opened in 1977.

77. GW community members helped administer about 2,500 vaccines during D.C.’s first high-capacity COVID-19 vaccination event in 2021.

Breaking Ground

78. GW now boasts thousands of professors, including 123 endowed chairs and professorships, seven members of the National Academies, a Pulitzer Prize winner for fiction, and dozens of former and active Fulbright scholars.

79. At the time the Columbian University Medical School and Hospital were rededicated as the George Washington University Medical School and Hospital in 1904, distinguished faculty included immunologist Walter Reed, who confirmed the theory that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquito bites, and groundbreaking epidemiologist Theobald Smith, who discovered the causes and transmissions of several infectious and parasitic diseases.

80. In 1928, the Department of Medicine, the Medical School and hospital were reconstituted into the School of Medicine, the School of Nursing and the University Hospital. While this original School of Nursing only existed from 1911 to 1931, during that time it was one of just a few providers of a formal medical education to women in the early 20th century.

81. The new GW School of Nursing would open in 2010 and has become a preeminent force in nursing education, particularly for veterans.

82. In 1927, GW historian Samuel Flagg Bemis won the Pulitzer Prize in History for his work Pinckney’s Treaty: America’s Advantage from Europe’s Distress, 1783-1800. He was just 35 years old at the time.

83. GW Psychology Professors Fred A. and Thelma Moss created the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), which is still in use today. In this photo, part of a driving test Fred Moss also designed, he demonstrates what not to do at the wheel of a car.

84. One of the most legendary GW scientists of the past century is George Gamow, who was already renowned when he joined the physics department in 1934. His broad scientific interests ranged from explaining radioactive decay to suggesting how genetic code could be described, but he is best known for developing the big bang theory of cosmic evolution.

85. George Gamow with students.

86. A native of Poland, Dr. Gamow and his wife tried to escape the Soviet Union multiple times before quietly defecting under GW’s auspices. According to his autobiography, on one occasion the Gamows tried to cross the Black Sea to Turkey in a kayak stocked only with eggs, chocolate, strawberries and two bottles of brandy. They were forced to return to shore after 36 hours of paddling, and Dr. Gamow spent several weeks in the hospital.

87. In 1934, Dr. Gamow agreed to join the GW faculty on three conditions: that GW also hire his colleague, scientist Edward Teller; that his initial appointment be described as “visiting professor” so as not to alert Soviet authorities of his intention to defect; and that the university help him organize an annual conference on theoretical physics in collaboration with the Carnegie Institution.

88. At one such conference held in GW’s Hall of Government in 1939, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Niels Bohr announced that scientists had split the nucleus of uranium, releasing significant energy.

89. The announcement would launch the atomic age. A plaque commemorating it now hangs outside Room 209 of GW’s Hall of Government.

90. A student with engineering equipment, 1971.

91. Julius “Julie” Axelrod received his Ph.D. in pharmacology in 1955, and in 1970, earned the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discoveries concerning nerve impulse transition. In 1971, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws from GW, and in 1974, he became a professorial lecturer in pharmacology at GW’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

92. GW doubled its campus research and lab space in 2015, when it opened the Science and Engineering Hall. Thousands of students and more than 140 faculty now conduct groundbreaking cross-disciplinary research in the building.

93. GW’s Elliott School of International Affairs boasts a Space Policy Institute, led by Scott Pace, former executive secretary of the White House’s National Space Council.

94. GW School of Business’ Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center is one of the world’s leading centers for financial literacy research and scholarship.

95. In 2020, a team of researchers at the Milken Institute SPH established a new laboratory processing thousands of COVID-19 tests a week to evaluate and protect GW’s on-campus population of students, faculty and staff.

96. Madison Lintner, senior research assistant in the Jordan Lab at the Milken Institute SPH, with materials for the COVID-19 vaccine trial.

97. GW served as a phase three clinical trial site for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, helping ensure the vaccine was safe and effective for a diverse population.

War, Peace and Activism Down the Ages

98. The first student protest was recorded in the Law School in 1872 over diploma fees.

99. In 1898, a junior named William L. Mitchell dropped out to join the U.S. Army. He would reach the rank of general and eventually be considered the father of the U.S. Air Force. Two decades after dropping out, he returned, finished his coursework and received his B.A. in 1919 “as of the class of 1899.”

100. Since its founding, the School of Nursing has supported veterans through scholarships, specialized resources, an accelerated bachelor’s degree option and more.

101. According to former GW President Steven Knapp, GW was known as the “Holiday Inn of the Revolution” during the Vietnam War because so many protestors took refuge in its residence halls.

102. More than 2,000 students attended a 1969 rally in University Yard opposing the House Un-American Activities Committee, at which activists Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman spoke.

103. In 1969, the Black Student Union and Student Board of Trustees worked together to organize a march on Rice Hall to protest the lack of scholarships for Black students, absence of classes on African American history and small number of Black faculty members.

104. That same year, 40 members of Students for a Democratic Society seized control of Maury Hall to protest what they believed was university complicity with the Vietnam War.

105. GW is often recognized as one of the top schools producing Peace Corps volunteers and Fulbright scholars.

106. The Store, a student-run food pantry in District House, helps bridge gaps in food security for the GW community.

107. In response to calls for action from students, GW is implementing a single-use plastics policy.

108. GW is now home to major research and policy initiatives on civil conflict in the U.S. and throughout the world, including the Program on Extremism, launched in 2015, and the Institute for Data, Democracy and Politics, founded in 2019.

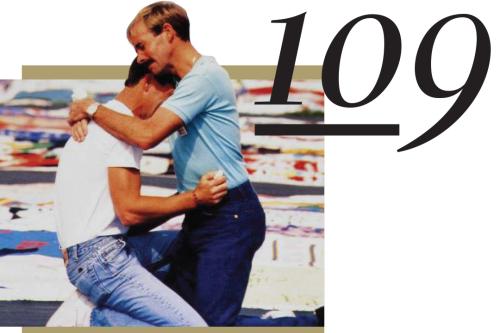

109. This photo of mourners at the AIDS Quilt on the National Mall appeared in the 1990 Cherry Tree.

110. In 1993, Honey W. Nashman co-founded GW’s Office for Community Service. In 2015, the associate professor emerita of sociology and human services made a major leadership gift to support GW’s engagement with local, national and international service at the renamed Honey W. Nashman Center for Civic Engagement and Public Service.

111. GW has held an annual day of service in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. since 1996. Since 2009, it also has held an annual service day at the beginning of the academic year at which thousands of students and other GW volunteers participate in service projects around the D.C. area. The first Day of Service coincided with a challenge from First Lady Michelle Obama to GW students: If they could complete 100,000 hours of community service during the 2009-10 academic year, she would speak at the 2010 commencement. They did, and she did. That fall, she joined in with GW students at the university’s second Day of Service

A Legacy in Art

112. In 1856, Columbian College introduced an art course, “Shades, Shadows and Perspective,” as a requirement for the BA degree.

113. In 1859, courses in art criticism and history were required of all Columbian College students, who were encouraged to study the private painting and sculpture collections of board members including philanthropist and collector William Wilson Corcoran.

114. Corcoran’s private collection became the Corcoran Gallery of Art, formally opened in 1874 at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 17th Street, NW. In 1878, Corcoran donated additional funds to establish an art school associated with the gallery.

115. In 1897, the Corcoran moved to a new Beaux-Arts building designed by architect Ernest Flagg, where it remains today.

116. Celebrating its 10th anniversary in 2021, the Corcoran School's popular annual NEXT exhibition showcases outstanding student art every spring.

117. In 2015, the George Washington University and The Textile Museum opened on campus. The museum boasts more than 21,000 examples of handmade textile art representing five continents and five millennia.

118. The Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collections, housed in the museum, comprise nearly 2,000 maps, prints and artifacts that trace the history of Washington, D.C.

119. While starring in “Joan of Lorraine” at Lisner Auditorium in 1946, actress Ingrid Bergman told journalists she was disappointed in the venue’s policy of segregation. The cast and crew signed a petition opposing the policy, and after a year of debate, the auditorium began allowing Black patrons. This clay sculpture by alumnus Calder Brannock commemorates the event.

120. In 2014, the Corcoran School—then known as the Corcoran College of Art and Design and now as the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design—became part of GW.

121. In 2018, the Corcoran School welcomed back works of art from the Corcoran Gallery to serve as the foundation of the Corcoran Study Collection, which is available to students, faculty, researchers and the public.

122. Among the materials in the Corcoran Study Collection are the journals of William MacLeod, the original curator of the Corcoran Gallery of Art. On July 2, 1881, he underlined in red pen an era-defining event: “Attempt to assassinate President Garfield!”

123. “Project Runway” host Tim Gunn earned his BFA in sculpture from the Corcoran in 1974 and later served as the school’s director of admissions.

124. Legendary “Twin Peaks” director David Lynch took Saturday classes at the Corcoran in the mid-1960s before moving away from D.C.

125. “Scandal” star Kerry Washington in her senior yearbook photo, 1998.

Presidential Ties

126. Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis graduated from GW in 1951.

127. A decade after her graduation, her husband, President John F. Kennedy, received an honorary Doctor of Laws and delivered a speech on University Yard at the inauguration of GW President Thomas H. Carroll. President Kennedy joked that “it took her two years to get this degree, and it took me only two minutes, but in any case we are both grateful.”

128. The Kennedys were not the only presidential family to receive degrees from GW. At Winter Convocation in 1929, for instance, President Calvin Coolidge and Grace Goodhue Coolidge received honorary degrees.

129. At Commencement in 1946, when his daughter Margaret graduated with her B.A. in history, President Harry S. Truman also received an honorary degree.

130. Bill Clinton was the first president feted with a GW inaugural ball in 1993.

131. In 1972, a former FBI agent named Alfred Baldwin kept watch from room 723 of the Howard Johnson hotel as a group of men attempted to break in and wiretap the Watergate offices of the Democratic National Committee. The ensuing scandal would bring down President Nixon and shape American politics for decades. In 1999, GW acquired the Howard Johnson building; room 723 was used for student housing.

132. GW’s special collections include a signed autobiography of G. Gordon Liddy, one of the scandal’s most notorious conspirators.

133. Thomas Mallon, professor emeritus of English, was a PEN/Faulkner finalist for his historical novel, Watergate.

134. GW emergency room physicians and faculty members successfully treated President Ronald Reagan when he was shot in 1981.

135. Head of trauma Joseph Giordano, GME ’73, former chair of the Department of Surgery, and Lewis B. Saltz, professor of surgery, were among the first doctors to treat Reagan, and Benjamin Aaron, now emeritus professor of surgery, was lead surgeon during the two-hour emergency operation.

136. In 1974, GW purchased the F Street Club, originally built in 1849 for U.S. Navy Captain Charles Steedman and afterwards a members-only club and a lodestar of the Washington social scene, which Eleanor Roosevelt called “a charming house.” Since its purchase by GW, Presidents Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton have attended events at the F Street House.

137. The house was rededicated as GW’s alumni house in 1999, and in 2008 was renovated to serve as a residence for then-GW President Steven Knapp. When Thomas J. LeBlanc became president in 2017, he took over the residence.

138. A satirical article in the 1977 Cherry Tree suggested GW might buy even more prestigious properties, like the White House.

139. President Carter visited GW in 2007 to discuss peace in the Middle East.

140. President Reagan at GW, 1991.

141. Former President George H.W. Bush and former first lady Barbara Bush delivered GW’s Commencement address on the National Mall in 2006.

142. President Clinton and his daughter Chelsea watched GW’s basketball team upset the top-ranked University of Massachusetts in 1995.

143. President Barack Obama and his family also caught a game at the Smith Center in 2009.

144. Then-Senator Joe Biden at GW in 1985.

145. It’s not just American presidents: GW students have learned from and interacted with a wide range of national and international guests. Visitors in just the last half-decade include President Emmanuel Macron of France, late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Apple CEO Tim Cook, Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and dozens of cabinet secretaries and members of Congress.

Hail to the Buff and Blue!

146. The original colors of Columbian College were blue and orange. They changed to buff and blue in 1904 when the college was renamed. The new colors commemorated the uniform George Washington wore when he resigned as commander in chief of the Continental Army in 1783.

147. In 1957, GW had the colors analyzed by the Munsell Color Company and standardized. These remained until the university developed its new identity standards, including color palette, in 2012.

148. Then-student Eugene Sweeney wrote “Buff and Blue” in 1924 as part of a contest to compose a new fight song for GW’s football team. In the 1990s, Patrick M. Jones rewrote the song so that it could be used for any GW athletic contest and titled it “The GW Fight Song.”

149. GW’s first official gym, known as the “Tin Tabernacle,” was completed in 1924 and stood in what is now University Yard. It was demolished in 1976.

150. Hall of Fame NBA coach Red Auerbach, M.A. ’41, who came to GW on a basketball scholarship, said playing in the Tabernacle as a student athlete had a major influence on his coaching technique. There was no room out of bounds, so players had to be able to stop quickly lest their momentum carry them into a wall. When Auerbach became a coach—on professional courts where the consequences of going out of bounds were less painful—he still emphasized spatial awareness and mobility in his players.

151. The Charles E. Smith Center, which now houses the majority of GW’s intercollegiate varsity sports, was built in 1975 and renovated in 2009.

152. Though football is no longer a varsity sport at GW, it thrived in the first half of the 20th century. The 1908 football team was GW’s most successful, winning the conference championship, then called the South Atlantic Intercollegiate Athletic Association, despite having no home field. The team had to rent one from the American League for $300.

153. In the 1920s, the football team was known as the “Crummen,” after coach Henry Watson Crum, and the “Hatchetites,” after the student newspaper.

154. In the lead-up to the 1948 homecoming game against the University of Maryland, GW fans kidnapped Testudo, the 400-pound bronze turtle statue that served as UMD’s mascot, from his pedestal in College Park, Md. Photos of shenanigans with the mascot appeared in the 1949 edition of the GW yearbook, The Cherry Tree, among them this mocked-up application to GW—sternly marked “Rejected.”

155. Cheerleader Ann Marie Sneeringer and football tackle Ed Rutsch, 1959.

156. Norm Neverson became the first African American to receive an athletic scholarship from the university when he was recruited for the football team in 1963.

157. Garry Lyle was the last GW athlete to be drafted by the NFL, by the Chicago Bears in 1967.

158. Men’s basketball started at GW in 1906. The team defeated Georgetown twice during its inaugural season, earning a trip to the Southern Conference Championship.

159. The GW women’s basketball team in 1922…

160. ….and in 2020.

161. GW’s basketball program has produced some of the school’s most successful athletes, including Yinka Dare, who led GW to an appearance in the NCAA’s Sweet Sixteen in 1993 before being drafted 14th overall by the New Jersey Nets the following year.

162. Dare wasn’t the only pro baller to come out of GW. Others standouts include Jonquel Jones, who was selected sixth overall in the 2016 WNBA draft; Pops Mensah-Bonsu, B.A. ’06, who played professionally for a decade, and double alumna Cathy (Joens) Engelbrecht, B.A. ’04, M.P.H. ’09.

163. Yuta Watanabe, B.A. ’18, now with the Toronto Raptors, was just the second player of Japanese descent to play in the NBA.

164. GW alumni have broken racial barriers in their Olympic sports. At the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens. Katura Horton-Perinchief, M.P.H. ’08, represented her native Bermuda as the first Black woman to compete in Olympic diving. And Aquil Abdullah, B.A. ’96, was the first African American Olympian to compete in rowing

165. The Ellipse on the National Mall, between the Washington Monument and the White House, was the baseball team’s official home until 1993.

166. The team got a clubhouse to call home in 2014, when trustee, alumnus and former GW outfielder Avram “Ave” Tucker, B.B.A. ’77, made a $2 million donation that supported student athletes and enhanced the team’s facilities in Arlington, Va.

167. GW’s official mascot, “George,” has taken numerous forms over the years, but has always involved a version of the Continental Army uniform and, usually, cartoonish headgear.

168. GW now has 20 men's and women's athletic teams, including baskeball, baseball, gymnastics and soccer.

169. George sometimes appeared with “Martha”…

170. …or even a horse named Nelson.

171. George joined the Washington Capitals’ Stanley Cup victory parade in 2018.

172. In 1934, a dog named Shorty served as an unofficial mascot, as did one named Smoky in 1947.

173. Then-president Stephen J. Trachtenberg presented a bronze statue called “The River Horse” to the Class of 2000 along with a quirky invented-origin story about hippos in the Potomac River.

174. The Marvin Center once contained a bowling alley.

Worth a Thousand Words

175. A fashionable crew of students in 1890.

176. Students in the library of Columbian College, 1892.

177. Board of the Columbiad, GW’s original yearbook, in 1898.

178. Columbian College seniors, 1898.

179. The Bicycle Club, 1899.

180. Elmer Louis Kayser, the university’s first official historian, had a 70-year tenure at GW, arriving at the university as a student in 1914 and remaining until his death in 1985.

181. A cartoon published in 1921 GW’s student satirical newspaper, The Ghost.

182. GW’s 100th Convocation.

183. Students with car, 1942.

184. Female students enjoy leisure time on the roof of Strong Hall in the 1930s

185. Scenes from a student election in 1957

186. Winter 1958.

187. Only at GW, late ’50s or early ’60s edition.

188. Registration Day at the Hall of Government, 1957

189. 1960 was the first time students registered using IBM punch cards instead of handwritten forms. This unidentified pup used neither

190. A reception welcoming international students in 1961. GW is home to 4,000 international students, faculty and staff, and nearly half of all GW students participate in study abroad programs

191. GW students have tea at the Embassy of Pakistan, 1954

192. In the student union, 1963.

193. The staff of radio station WRGW, 1982.

194. The Marvin Center housed a short-lived barbershop in 1970. Its proprietor blamed the closure on the “long-haired thing” then in vogue-as modeled by this student from the 1970 Cherry Tree.

195. Laid back in the early 1970s.

196. Playing pool in the Marvin Center, 1971.

197. GW students, 1983.

198. Goofing around, 2000.

199. Student trends on campus, 2009.

200. A graduate watches 2020’s virtual Commencement.

Photo Credits: 1. Rembrandt Peale // 18. Elmer Louis Kayser // 28. William Q. Force // 45. Wikisource // 58. U.S. Library of Congress // 85. GW Magazine // 110, 111, 115, 160. William Atkins // 126. GW Historical Materials // 200. Sydney Elle Gray

Unless otherwise noted, historic images courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center of the George Washington University Libraries.

Special Collections Research Center

With 200 years to cover, this article is far from a comprehensive collection. For more, please visit the Special Collections Research Center.