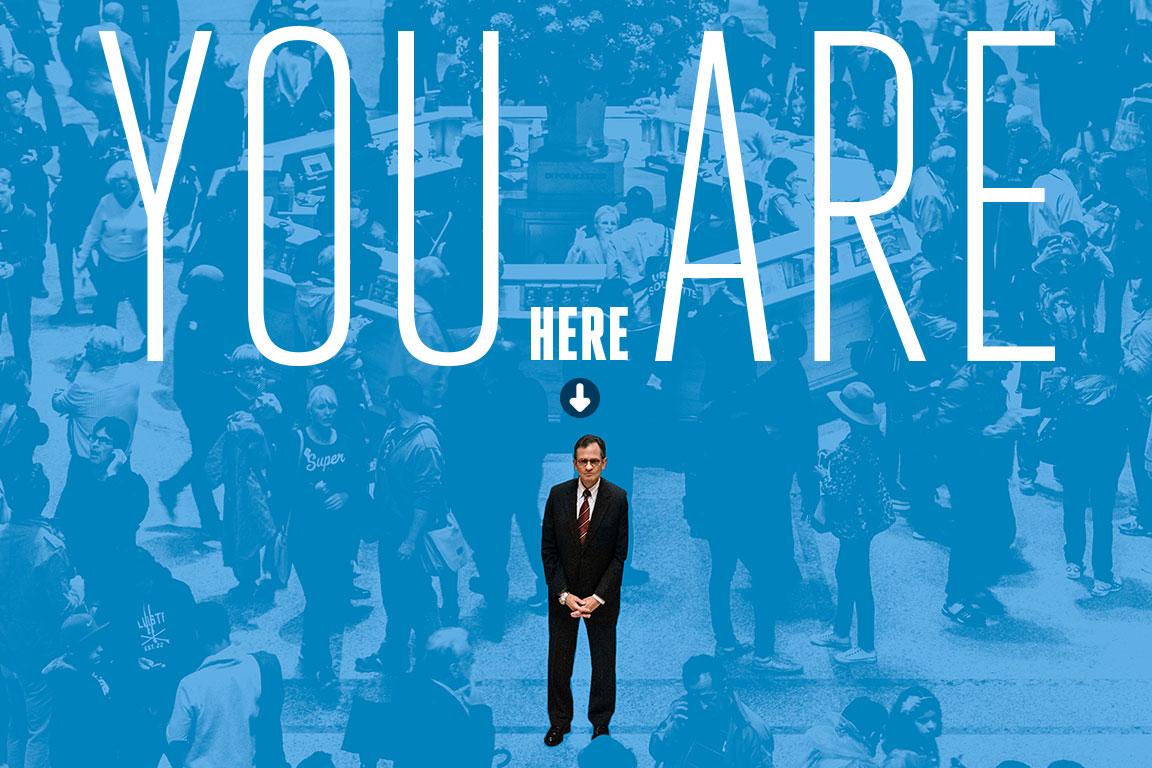

You Are Here

(Photo Illustration/John McGlasson)

As president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Daniel Weiss, BA '79, finds his way anew on familiar turf.

Story by Julyssa Lopez | Photos by William Atkins

AMONG MORE THAN A MILLION OBJECTS AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART—BETWEEN

RENOIR portraits in gilded frames and full-body Rodin sculptures cast in bronze—there are hidden hallways and secret pockets that lead to the nervous system of the institution. The 2.1-million-square-foot building tucks its office and operational spaces behind almost 400 majestic galleries like a secret labyrinth.

Swing through an inconspicuous door next to a Renaissance painting and you may find 15 conservators staring up at you from a restoration lab on the other side. A staircase could lead to a row of cubicles where members of the marketing and external relations department are answering media inquiries. In the southwest corner, you could end up in the facilities department, where around 175 employees provide support services for the monumental museum. These areas are where objects are cared for, where exhibition labels are written, where financial plans are made.

On the ground floor, a small, shadowy corridor snakes behind a security desk and leads up a few floors to a control room of sorts.

This is the realm of Daniel Weiss, BA '79, the Met's new president and chief operating officer, and the man in charge of the bustling metropolis behind the country's largest museum. He is the mechanic keeping all the museum's gears in motion.

Dr. Weiss has only been in his position since July, but already his office feels lived in. His baroque desk is covered in neat stacks of paper that detail the museum's day-to-day operations. A book on portrait painter John Singer Sargent, who was featured in one of the Met's exhibitions last year, sits on a tabletop. A packet with updates about the museum's new public space, the Met Breuer building, lies nearby, decorated in a mosaic of Post-it notes.

The new leader is settling into a rhythm and learning to navigate the complexities of the 145-year-old museum. As the former president of Lafayette College and, most recently, Haverford College, Dr. Weiss knows how to find his way around large institutions. He compares the Met to a college campus, with dozens of departments, personalities and dining options.

But that doesn't mean the Met's numerous wings and winding layers aren't a challenge. The space can be a nightmare for a new employee trying to get a lay of the land. "It's almost like Batman's mansion, the public and private space here," he says.

Dr. Weiss squints through his round-rimmed glasses and walks toward his window.

"Can you see that?" He taps on the glass, gesturing toward a line of rooms visible on the other side of the museum. People the size of ants move around inside.

"Right there. Those are laboratories for object conservation. They're in pockets all over, and you wouldn't know it from inside." He stands for a moment watching the conservators from afar. He's still learning how each piece moves and connects to the whole. But he's figuring it out quickly—he has to, now that he oversees 1,500 of the museum's 2,200 full-time employees in all administrative areas.

When news circulated that Dr. Weiss would take the helm as president of the Met, The New York Times noted the museum's decision to "combine both business acumen and scholarly credentials" by hiring a "medievalist with an MBA." Dr. Weiss studied psychology and art history at GW and got a master's degree in art history from Johns Hopkins University in 1982. He then earned an MBA from Yale University in 1985 and spent years as a consultant for the management firm Booz Allen Hamilton.

"Imagine having the opportunity to spend time in your favorite place in the world every day."

Dr. Weiss returned to Hopkins and, in 1992, completed a PhD, with a concentration in Western medieval and Byzantine art. He taught there for several years, becoming the dean of the Krieger School of Arts & Sciences. Later, he served as president of Lafayette College and Haverford College.

His new role can be seen as the culmination of those experiences. He was brought to the museum to be a "thought partner," Met Director and CEO Thomas Campbell told the Times, and to supervise departments that range from fundraising to the museum's archives and its shops. Technology and information services, legal affairs, security and construction, and merchandising and government relations are just some of the responsibilities that fall under Dr. Weiss' purview now.

He must find his footing at a time when the Met is in the midst of expanding its digital presence and duplicating its collection online. It's also renovating several galleries and preparing to open an outpost for modern and contemporary art at Manhattan's landmark Breuer building, the former home of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

If Dr. Weiss is overwhelmed, he doesn't show it. His posture is relaxed in his dark suit in a way that communicates approachability. He is enthusiastic, quick to crack a smile as he discusses his new role. He trusts his experiences will guide him. But there's something else to the way Dr. Weiss talks about his job: a touch of incredulity. After all, he is an arts lover who gets to operate what is arguably the most important cultural institution in the country.

"Imagine having the opportunity to spend time in your favorite place in the world every day," he says.

Dr. Weiss walks around his office and extends a finger toward the pale green walls, which are minimally appointed with paintings that he handpicked from the museum's collection. He remembers, as a freshman, going to the National Gallery of Art and buying a poster of a painting by British Impressionist Alfred Sisley. He mounted it proudly over his bed in Thurston Hall.

Now, a real Sisley—an oil painting of a wintry scene—hangs to the left of his desk.

IT'S SOPPING WET ON AN OCTOBER AFTERNOON IN Manhattan. A category 4 hurricane that had been projected to hit the city veered off course but still left juddering winds and a bitingly cold rainstorm. Pedestrians on Fifth Avenue seem to have the same idea in mind: Find shelter.

The towering structure of the Met, with its sculptural columns and Beaux-Arts façade, offers relief from the weather—and New Yorkers and tourists alike know this. Crowds of people slosh up the building's majestic stairs under the canopies of their umbrellas.

"It's bigger than I imagined," one woman says, her rain boots squeaking as she makes her way through the Met's massive doors. She cranes her neck up at the museum's main artery, the Great Hall. The stunning entrance unites several galleries. It's also the principle route Dr. Weiss takes to get through the schedule of meetings that his assistant leaves on his desk every morning. The itinerary is printed on two or three double-sided index cards that fit neatly into Dr. Weiss' jacket pocket.

He often bustles from one corner of the museum to another, running directly into tourists gaping at the building's palatial arches. "Sometimes I have to remind myself I'm not in Grand Central," Dr. Weiss says with a laugh. "When people are walking slowly, they're doing exactly what they're supposed to do. They're enjoying the art."

His morning started at 8 a.m. today when he walked into the museum from the Park Avenue apartment he is renting a short distance away. He had back-to-back meetings with two of the museum's trustees—he has scheduled several of these every week to get to know the board members individually. Then, Dr. Weiss walked down a flight of stairs to introduce himself to lawyers in the general counsel's office and staff members from the archives department.

Because of the severe weather conditions, Dr. Weiss convened the museum's senior staff and led a meeting to examine emergency and preparedness protocols. Leaks caused by storms can be the mortal enemy of centuries-old paintings and delicate sketches on paper. Part of his role includes the guardianship of the collection, so he has to think about everything that could affect the museum's more than 1.5 million objects. The paradox is keeping the museum both accessible to the public and also secure. (Weeks later, he held a similar meeting to address security in the wake of the Paris attacks.)

"The most important thing an art museum does is protect the art," Dr. Weiss says. "If you don't do that well, everything else doesn't matter."

At lunchtime, he walked across the street to one of the restaurants dotting Madison Avenue for a meeting with his predecessor, Emily Rafferty. She retired last spring after almost 40 years at the museum. Exalted for her fundraising skills and poise, Ms. Rafferty was the first woman to helm the Met's operations. She also seemed to possess an alchemical ability to be in multiple places at once. She'd represent the museum at events across New York City, appearing elegant and perfectly coiffed every night.

"The most important thing an art museum does is protect the art. If you don't do that well, everything else doesn't matter."

Hers are difficult—and stylish—shoes to fill, but Dr. Weiss is stepping into the role with aplomb. As Ms. Rafferty did during her tenure, Dr. Weiss serves as an ambassador of the museum at galas and donor receptions. One of his assistants guesses that he has an event almost every night, which stretches his daily schedule to nearly 12 hours.

The parade of meetings makes every day different for Dr. Weiss. He was up early one morning to give the prince of Japan a private tour of the Asian galleries. Another day, he met with a young woman interested in starting her own arts business in Manhattan. His agenda is about as unpredictable as the splatters of a paintbrush.

"It's a very big portfolio—the entire administrative side of the museum," Dr. Campbell, the museum president and CEO, says in a phone interview. "But Dan has an insight to problems and judgment and experience that I think is exceptional. I already feel secure in having him in charge of the various parts."

As an art historian, Dr. Weiss also understands the cultural context and pedagogy that goes into the museum's exhibitions and programming. He has been visiting the Met since he was a high school student on Long Island, N.Y., and as a professor he would bring students to the galleries to experience art firsthand.

"I've taught here, I know the material and I understand the museum very deeply," Dr. Weiss says.

His years of art history seep into daily conversations. Just this afternoon, he found a 20-minute gap between his hourly meetings and phone calls and used it to wander to the expansive Tisch Galleries and watch the installation of the fall show "Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom." He spent time with the curators, discussing the 230 works that represent Egypt's artistic and cultural traditions between 2030–1650 B.C.

Dr. Weiss' affinity for art history started his freshman year at GW. He had enrolled as a psychology major and needed one more class to round out his schedule. He ended up taking an art history class with Jeffrey Anderson, now a professor emeritus of art. "He was absolutely transformational for me," Dr. Weiss says. "He was this young guy who was super articulate, extraordinarily passionate about what he was doing and wicked smart. I was just mesmerized by him and his passion for this art."

Back then, Dr. Weiss admits, he was a bad writer. The first paper he wrote in a freshman English class got a D-minus. ("And even that was a gift," he says.) Dr. Anderson helped him improve his writing. At the end of his senior year, Dr. Weiss won an award for the best paper in the art history department.

The experience energized him and compelled him to stay on the art history track. And he won a lifelong mentor and friend—he visited Dr. Anderson in Chicago just before starting his job at the Met.

ASIDE FROM HIS ART HISTORY EXPERIENCE, Dr. Weiss has something else working for him in his new role. Dr. Campbell is quick to point it out: "He's got a fantastic sense of humor, which is hard to find in people."

He is good-natured and relaxed on a day-to-day basis. When the museum's finicky glass elevator makes a painstaking pause on every floor, Dr. Weiss doesn't stress over showing up late to a meeting. He diffuses the situation. "We're on the local train, guys."

He appears unfazed even when it comes to large-scale projects. Among the Met's top priorities is preparing for the opening of the Met Breuer building, which will focus on modern and contemporary art.

The new location opens with two exhibitions in March 2016, a debut that comes with some pressure. Observers have been waiting since 2011 to see what the Met will do in the space.

Meanwhile, the museum's staff is building up the Met's digital presence and offering ways to engage with the collection online.

Both projects are designed to engage art lovers all over the world—and they are mammoth

undertakings. Yet Dr. Weiss talks about them calmly and says that his lengthy career guides his thinking and leadership on these two initiatives.

"There are certain central themes that unite all the institutions where I've worked: the primacy of hiring outstanding people, providing staff with the support they need to do their jobs, listening carefully to what it is that they do," he says.

Some of his management philosophies were adopted from his time as a consultant for Booz Allen. The job required him to pay attention precisely to the needs of clients. It taught him to listen, he says, and to try to understand his colleagues' perspectives as much as possible.

He started the job shortly after receiving an MBA from Yale in 1985. He was working in New York and building a professional portfolio. But despite the skills he was gaining, something was off. "I wasn't reading The Economist on the train. I was reading The Art Bulletin," he says.

Dr. Weiss would think back to his undergraduate art history classes and eventually realized that he hadn't just enjoyed the material—he had unlocked his passion. So he quit his job.

"It was risky," Dr. Weiss says. "I gave up a good job and a good income to sleep on the floor in my friend's apartment and live on a graduate student's stipend while I got a PhD—and I knew that when I finished the degree, there would be no guarantees of a job."

His wife, Sandra Jarva Weiss, BA '80, JD '83, saw it as a much more straightforward decision.

"It was clear that seeing art on vacations wasn't going to be enough for Dan," she says. "He needed to fuel that interest and that passion."

She understood his dedication to art. It was their mutual interest in the subject that brought them together at GW.

They have identical memories of the day they met. Dr. Weiss had taken a part-time job at the Kennedy Center shop his sophomore year. Ms. Jarva Weiss had come to the Kennedy Center during her first few weeks at GW and scored a job as an usher. She'd seen him walking back and forth along the halls to stock the shelves.

He remembers noticing a beautiful blonde in the Kennedy Center's black-and-burgundy uniform. She remembers him nodding a shy hello and making small talk about the shows on view at the theater.

The next day, Dr. Weiss had to wake up early for his 9 a.m. shift. He wandered into Thurston Hall to grab coffee before heading to work.

"On a Saturday morning, at 8 o'clock, there's no one down in the basement of Thurston having breakfast—except for one person," Dr. Weiss says. It was Sandra, the girl he had met the day before, clad in her Kennedy Center uniform. "It hadn't come up that we were both students at GW," Ms. Jarva Weiss says. "But there we were."

They became fast friends. Dates involved biking to the National Gallery of Art and enjoying the Smithsonian museums. Now, more than 30 years later, dates involve strolls through the Met's Greek and Roman galleries at night, after the tourists have gone.

Dr. Weiss splits his time between New York and Pennsylvania, where his wife still lives while their youngest son finishes high school. Ms. Jarva Weiss plans to move to New York next year. Dr. Weiss says he makes the distance work—he hops a train on the weekend and occasionally comes home during the week. A couple of days ago, he rushed to Pennsylvania for his son's back-to-school night and then was back in New York by 5 a.m.

He inevitably has had to reduce the number of things on his to-do list. Among them, he put aside the book he's writing about a Vietnam War poet named Michael O'Donnell.

"It was clear that seeing are on vacations wasn't going to be enough for Dan," His wife says. "He needed to fuel that. interest and that passion."

Dr. Weiss learned that Mr. O'Donnell was a pilot who was shot down shortly after publishing one of his poems. The anecdote moved Dr. Weiss enough to start the project and he got deep into the research but had to stop when he took the job at the museum. He promises he'll get back to it once his schedule settles down a bit.

"I feel very drawn to this character and his powerful story," he says. "If something moves you, the odds are that there's something there that you can tell others about."

The idea reflects, in a way, how Dr. Weiss feels about art history. The stories found in the museum grip him repeatedly as he's walking through the galleries. He's getting ready to wrap up his day and jump on a train home to Pennsylvania for the weekend when suddenly a room full of portraits by John Singer Sargent catches his eye. He doesn't have a lot of time before the train leaves.

"Ten seconds—just 10 seconds!" he says to the staffer trying to get him through this final meeting, and he darts into the gallery. He stops in front of a 9-foot portrait Sargent painted in 1899. It depicts the beautiful Wyndham sisters, who came from an aristocratic family in London. They lounge in their glimmering silk dresses and illustrate the elegance of the era's society women.

"Henry James said of Sargent that at the very beginning of his career, when he was still very young, it was clear he had nothing else to learn. He was that good," Dr. Weiss says.

He lingers in front of the painting a few more moments. Then he turns and begins walking out of the gallery when a voice interrupts him.

"Daniel Weiss? Daniel Weiss!" A security officer is peering over excitedly, waving an outstretched hand. "How are you?" she says. "I haven't been able to meet you yet!" Dr. Weiss smiles and waves back. "It's so nice to meet you." He stops for a few moments to talk with her.

More and more, he is becoming a fixture in the museum. "I've only been here three months, but it doesn't feel like that. In some ways it feels like I've been here a long time," he says. "I'm gradually not the new guy."

Other Winter Features

Just Passing Through

With the automobile boom in the rearview and the Interstate Highway System ahead, a professor spent the late 1960s and '70s documenting a moment in time on the American road.

Jonquel's Best Shot

The Bahamian standout took a 900-mile leap and landed as one of the WNBA’s top prospects.