If This Hall Could Talk

Ahead of a major renovation of Thurston Hall, GW Magazine delves into its history—the joys, the tragedies and the birthday pies to the face—as told by denizens from the past half-century.

By Danny Freedman, BA ’01

In 200 years, no GW touchstone even comes close. Not the appearance of President James Monroe and the Marquis de Lafayette at the first commencement or the hippopotamus outside Lisner; not the aura of the Tin Tabernacle or the patchwork athletic glories; not any mark of physical and academic manifest destiny.

None of them has become living legend quite like Thurston Hall.

For decades Thurston has been the magnet on the edge of campus that attracts as strongly as it repels. It is college concentrate: more than a thousand teens funneled into nine floors—mostly four to a room—all of them utterly on their own together.

“Thurston is a dorm of unending chaos, excitement, noise, people and frustrations,” as The Cherry Tree yearbook distilled it in 1978. While the mechanisms of those joys and pains may have changed, the feelings remain.

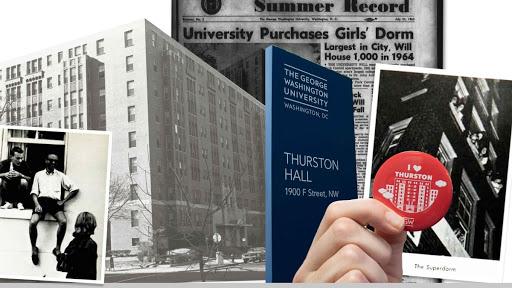

The building itself, originally the Park Central apartments, is nearly a century old. The university bought the building and in 1964 re-opened it as a women’s dorm, switching to co-ed in 1972 and, later, freshmen-only. Today it’s a structure that seems as if held together by cement and lore and smears of toothpaste reaching back to Lyndon Johnson’s administration, which plug a galaxy of pinholes in every wall.

It’s endured 56 years of far more waking hours than sleeping ones, a perpetual spasm of youth on an otherwise august street that dead-ends at the tip of the executive branch.

“I’m told that there are no windows or clocks in casinos in Las Vegas because they want people to have a sense of timelessness—just keep gambling,” former President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg told The Washington Post in 2007. “That’s sort of how it is in Thurston.”

Even timeless things do change over time, though. The Thurston that saw tear gas and

nightsticks at its doorstep in the 1960s and ’70s was different than the Thurston of the 1990s, where there was Mario Kart, a lot of Domino’s pizza, cable TV and in the basement an all-you-can-eat cafeteria. And the Thurston of just a year or two from now will be a radical shift from the Thurston of recent years.

After this semester the building will be taking on a major interior renovation, under a plan approved by the Board of Trustees last summer. Unlike past iterations of Thurston, this will be a sweeping redesign: plans call for a sky-high atrium and sunlit courtyard, city views from the top floor, outdoor terraces and other spaces for students to study and gather. Thurston still will house a heap of freshmen—more than 800—but in neat stacks of double- and single-rooms.

The work is aimed at making Thurston “a point of pride for the university,” President Thomas LeBlanc has said.

Gone will be the building’s age spots and some of the perennial injustices that always are ground to peccadillos by hindsight. Gone will be whatever was the most recent definition of “surviving Thurston.” In time they’ll be replaced by new ones.

What will remain are the ghosts of youth—celebrated in the stories that follow—and a name and a red brick facade that shoulder all this history into another decade.

Shenanigans and Tomfoolery

A Neighborly Invite

I was getting ready to move and found the letter deep in a storage bin with my old GW ID. We knew that Chelsea Clinton was at Sidwell Friends at the time, and back then she’d gotten a hard time in the press and was under a microscope. I think we just thought: We should hang out with her. That sounds like fun.

I don’t even remember what we wrote in our letter or what we’d hoped would happen. I think we just wanted to hang out. We weren’t trying to get to the White House, we just wanted to be friends with her.

When we got the letter back, I’m sure we probably were super excited. We probably thought: This is it, we’re hanging out. And then it was just a letter from the director of correspondence, which I don’t think we even knew was a job that existed. We had no frame of reference. Now, looking back on it, I just laugh and think we were so naive to think that would actually be a thing. That’s cute of us.” — Meredith Goldberg, BA ’00 (as told to the author)

A Window of Opportunity

In the spring of 1967, a group of us bought at auction the right to first choice of a room at Thurston “Superdorm” Hall for the following academic year. We chose a suite for six on the second floor—Room 210—so we could easily climb in and out of the window to dodge a curfew that was in place at the time.

That window served as an auxiliary entrance and exit for many Superdorm residents throughout the year. Perhaps the most dramatic was the exit by two male friends disguised as women, dressed in stolen clothes of mine. They entered the dorm through the main door, walked up to our suite and each threw a pie in my face to celebrate my birthday! They jumped out the window and ran off. — Hazel Weiser, BA ’70

Cosmetics Fix

On the last night of freshman year only one of my roommates and I were left in our room. Another roommate, who had already left, had peeled nearly all the paint off the wall by her bed over the course of the year, leaving the area almost completely discolored, and we worried that we might get fined for it.

My roommate found a bucket of white paint in the laundry room and brought it back to our room, where one of our friends somewhat jokingly suggested we paint the wall. We didn’t have paint brushes, and we definitely didn’t have money to buy any, so our friend ran to her room and grabbed old makeup sponges and brushes. We managed to paint the entire wall with beauty blenders and old brushes—and even more shocking, it actually looked decent. When it dried, you couldn’t tell the difference from the rest of the room. — Mae McGrath, CCAS ’22

Political Ground Zero

Heading Into (and Out of) the Storm

In September 1969 my mother drove me from Boston to D.C. with all my stuff in the car for school. When we pulled up in front of Thurston, there were three tables out front with radical groups recruiting freshmen: The first table was the Weathermen, the second was the Students for a Democratic Society and the third table was the Black Panthers. My mother was horrified—I was a kid from a local public high school in Waltham and she was really uncomfortable about leaving me. And I said to her, “No, I’m here. I’m going to school.”

It was at the height of the Vietnam War, and D.C. was overrun with strikes and moratoriums where young people from across the country ascended upon Washington to march. Being four blocks from the White House, Thurston was an amazing destination for kids from all over the country. I have vivid memories of busloads of kids from other universities just unloading in front of Thurston. They had no place to live—they just all got out and into the lobby, and that was it. I don’t think they cared where they stayed, and the lobby gave them a roof over their heads. It was what was known as a happenin’, and they could just experience the happenin’ and be part of the action.

The dorm, along with Mitchell Hall and everything else in that area, was tear-gassed constantly due to the strikes and moratoriums. Even though I wasn’t on the street when those happened, I remember feeling the uncomfortable results of the tear gas—eyes watering, sneezing.

It was a mixed feeling to be there at the time. On the one hand, it was mobbed and there was nowhere to go. And on the other hand, we were in the middle of the action.

One of these strikes was around the time of finals—probably in the spring of 1970—and GW closed; we were all told to go home. I saw one of my professors and he just said, “Go home.” My parents wanted me to come home, too, because it was crazy down there. And I remember, in the midst of it all, going to the airport and flying to Boston. — Ellen Zane, BA ’73, vice chair of the GW Board of Trustees (as told to the author)

Surviving the Night

As Thurston staff in the 1970s, we had a saying: “We’re housing the revolution.”

Student dress was military surplus, tie-dye, bell-bottom jeans, black arm bands for solidarity, heavy shoes, always a gas mask—and of course some type of bookbag for class. Anyone who wore their reserve uniforms—and many on campus were reservists—had a hard time navigating the streets.

Many times classes were cancelled due to chaos on campus. There was an especially difficult October week when there was a very large protest that drew thousands of students from all over. Many had friends in Thurston, so of course they were “bunking it” here. We were way over our normal occupancy.

One scary evening, armed National Guard troops were at our doorstep. We watched as students were being clubbed trying to get to the doors. Tear gas was everywhere. Tension was very high and we realized that a false fire alarm would empty everyone in the building into a very bad situation outside. Our solution was to put staff monitors at every fire alarm.

Happy to say we all survived that night and kept our residents safe. And difficult times can lead to enduring friendships: Fifty years later, two of my closest friends date to Thurston Hall. — Jane Stecher, MEd ’70

Short Takes, Social Media and Et cetera

Living on a Sometimes Front Line

We were in the thick of it in D.C., and being in F Street-facing rooms gave me a front-row seat. I watched during the 1971 May Day anti-war demonstrations as the heavy park-like benches that sat in front of the dorm were dragged into the street to block F Street. They were crushed by National Guard tanks. The dorm was tear-gassed and we were under martial law. — Tina Silidker, BA ’74, who lived in Thurston from fall 1970 through spring 1972

Probably How ‘The Fonz’ Did Laundry, Too

Two roommates and I lived on the third floor, next door to the laundry room. Sometimes we would hear a very loud crashing sound—periodically a few male students lifted or tilted the coin-operated laundry machines with all their strength and threw them back on the ground. Apparently the machines then started to work without inserting coins. — Helene Brecher, BA ’78

‘Done With Dorms’

Thurston was so large, and so densely populated, that after my master’s [degree], I decided I was done with dorms. Entry-level jobs in my new higher-education profession—student personnel work—were mostly dorm-director jobs. I changed course, never used my master’s for student personnel work, found an entry-level job through The Washington Post classifieds, and began the management consulting career that’s lasted until now. — Leslie Bobrowsky (Zuckerbrot), MA ’71, who was a first-floor RA while getting her master’s degree

Kitchen Confidential

Every floor had a lounge with a TV, couches and a small kitchen, which had an oven. The only time I ever cooked was to bake hash brownies for [my roommate] as she was recovering from leg surgery at GW Hospital after a skiing accident. How naïve. Luckily, she didn’t suffer any untoward effects from these. — Marilyn Barton, BA ’73

Thurston: A Timeline

1821

U.S. Congress charters Columbian College, President James Monroe signed the act.

1888

Mabel Nelson Thurston becomes the first—and, for a year, the only—female to attend the undergraduate Columbian College, part of what then was called Columbian University. The next year, 11 women joined her in Columbian College. (For the university as a whole, its first four female students were admitted to the medical school in 1884, producing GW’s first female graduate—Clara Bliss Hinds, in 1887—before the med school in 1892 re-banned women for the next 19 years. In 1888, two women earned bachelor’s degrees from the university’s Corcoran Scientific School.)

1964

“Superdorm,” as it was known in the beginning, opens as a women’s dorm, in the former Park Central apartments at 19th and F Streets NW.

1967

The residence hall is named for Mabel Thurston.

1972

Thurston becomes co-ed.

1979

Fire engulfs the dorm’s fifth floor, injuring some three dozen students as 900 residents scrambled out of windows and doors into the pre-dawn cold. Many at first assumed it was another false alarm. A D.C. fire battalion chief told The Washington Post the department sometimes responded to as many as three alarm pulls per night at Thurston.

1989

President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg, who led GW from 1988 to 2007, bunks with students in Thurston Hall for a night, which he made a tradition of doing. The occasion invariably led to prank calls (“billions,” one of his student hosts in 1990 told The Hatchet, before they disconnected the phone) and gag pizza deliveries to the room.

1992

Domino’s Pizza says that it delivers more pies to Thurston than to any other dorm in the nation.

1993

Security cameras added to every floor of Thurston to crack down on fire-alarm pulls, which sometimes happened multiple times a night.

2018

A first-generation college student “living and learning community” is established on eighth floor.

2020

Thurston closes for renovation and is expected to reopen by fall 2022.

The Fire

College and city life were, to an Ohio farmer’s son, a wondrous fire hose of experience—even the night it all nearly crumbled.

I arrived at Thurston Hall in the fall of 1974 to the windows all open with stereos facing out toward F Street in a cacophony of party.

In applying to college, my only thought was escape from my Ohio farm upbringing. Our local judge played on the GW football team in the 1930s, and I loved politics, so GW was the only college to which I applied.

I lived on the International Floor in a six-person corner unit. My roommates and I talked sex and girls and science and pop culture, politics and why we left our families.

I cried the first night, but never again.

My finances were desperate, but with student loans and work—as an usher at Lisner Auditorium and as a telephone operator at a switchboard (primarily serving the hospital … but also sometimes connecting the lines of two friends and listening to the confusion unfold)—I paid for my tuition, dormitory and food ticket.

Before Thurston, where I stayed my freshman and sophomore years, I’d never seen the poverty of a big city. I’d also never tasted alcohol (or any drug), an awakening that led my sophomore roommate and me to stock an exotic bar in our closet, and launched an interest in learning about wine. And our location at the center of the federal government became a reality of daily life. Friends in Thurston worked in the State Department, in the White House and in Congress—myself included, interning for Sen. John Glenn, the astronaut.

Walking to Thurston in the dark one night after studying at the library, Sen. Bob Dole, who would be Gerald Ford’s running mate, popped out of the F Street Club across the street. He talked with me for 15 minutes. When I arrived at my room, I called my parents to tell them the news. My mother met me with an equal report. “We have good news ourselves: We had a second crop of lima beans!”

Never have I forgotten the distinction between values inside of the D.C. Beltway, and the reality everywhere else.

To begin my first year of law school, in fall 1979, the housing office hired me to be an RA on Thurston’s fifth floor—but there was a shakeup on the floor that spring and they asked me to step in early. The housing director told me that I should not worry about programming, but just survive.

I was optimistic. I should have known better.

Thurston had continued to get more and more out of hand in those years. Every night someone would pull a fire alarm, requiring evacuation. Residents routinely used fire extinguishers as squirt guns and would put ammonium nitrate on door handles to explode upon touch.

When I unexpectedly took over as the RA, there was always hateful graffiti or property damage, as though it were a group joke instead of a safe residence. Students were just getting more and more brazen.

On April 19, a friend and I awoke to fire coming through all four sides of the door to my room. I thought, This place is going to burn down; I could hear everybody screaming through the windows into Thurston’s central courtyard trying to get out.

With the smoke and fire consuming my room, I reached out of the window and grabbed a copper utility wire, wrapped it around my right hand and slid down three stories with my friend, and fell the last two to safety.

I was fine, it seemed, except for my right hand where the wire cut down to the bone. The student in the room next to mine suffered burns on most of his body.

The guilt over my inability to help my residents was painful. I’d always felt overly responsible, even growing up. In Thurston I felt like I was there to keep order and I didn’t do that. That was the joke: no one could keep order. But I remember my students’ screaming, “help me, help me, help me.” That just doesn’t go away.

I recall awakening one morning afterward, showering and dressing. As I sat on the edge of my bed tying my shoes, I looked at the clock and noted the time to go to breakfast. Next, I returned my gaze to the clock and noted the time to go to dinner. I had sat on the bed unconscious the entire day. For a short time, I would find myself walking into street signs outside.

In the aftermath, I was impossibly conflicted. To the housing office, I was their on-site contact with necessary answers; to fifth floor residents, I was the guy to make things better. I mostly tried to focus my energy on putting others at ease—being positive and encouraging, asking how they perceived the fire and what I could do to help. It was a big moment of growth for everybody who was involved, and it was formative for me, too.

At age 64, I see the lateral scar on the back of my right hand, ever fading with the memory. In the long view, the fire was a minor part of my great time at GW—just one night in seven years. It was just another growing experience of many. — Luther L. Liggett, BA ’78, JD ’81

‘For Exceptional Performance While Under Fire‘

In my senior year, I was one of the RAs on the eighth floor of Thurston in the spring of 1979 when there was a significant fire in the building. This certificate was created by another RA in Thurston and presented to each of us who were on the residence hall staff that night.

The figures in the upper-right reflect part of my own story: The smoke got so thick on the eighth floor that, after getting students to evacuate, a security guard and I retreated into my room on the interior of the building. We put some wet towels at the foot of the door and went into the bathroom to move farther from the smoke. The RAs had been well trained to counsel students to keep their window screens undamaged, or a fine would be assessed. On that night of the fire, the guard opened my bathroom window and pushed out the screen. My first thought was that I would get assessed for my now missing screen. — Jim McPhee, BA ’79

"Adulting"

A Faculty Perspective

I was frankly a little terrified. It’s Thurston, it has a reputation. D.C. tour guides would go by on Segways and I remember distinctly my first semester one of those guides pointing to the building and saying, “That’s Thurston Hall of the George Washington University. It’s the third largest freshman dorm in the country.” But I haven’t found that Thurston lives up to its reputation. It’s delightful.

I’m currently the faculty-in-residence, and I’m in my fifth year. There’s a faculty apartment—if you head off to the right when you enter, just before the elevator there’s a little hallway, and my apartment is at the end of that hallway. It’s a proper apartment with a kitchen, dishwasher, and washer and dryer. It has a huge front room and that’s my public space, where I host students. So I have my privacy and then I can also open it up and invite in these wonderful young people who are in this threshold year of their lives, and are curious and open and smart.

"There’s a faculty apartment—if you head off to the right when you enter, just before the elevator there’s a little hallway, and my apartment is at the end of that hallway. It’s a proper apartment with a kitchen, dishwasher, and washer and dryer."

I’d known about the faculty-in-residence program. And as I was moving into a more administrative role as deputy director of the Writing in the Disciplines program, and was going to have more meetings and a more varied role on campus, I thought it’d be really great not to have a commute. And I teach in the first-year writing program—I really like first-year students. I think it’s a very exciting year. Plus I had never lived in a dorm. I went to community college for a couple of years and then I transferred to Georgetown and lived off-campus. So I thought this would be new and different, and that was part of the appeal.

When an opening came up, I sold my condo in Congress Heights and moved to Thurston.

I think a faculty-in-residence was a bit unusual for the students to wrap their heads around, and there was some uncertainty about my role, but then again first-year students also don’t really know what to expect.

It was easy for me to introduce myself to them as somebody who taught in the first-year writing program, which every student participates in. I began hosting events to help them explore the city’s institutions, history and longstanding issues, like gentrification—we’ve done walking tours of Shaw with a community organization, followed by a meal at Ben’s Chili Bowl, and every semester we visit NPR to spend time with film critic Bob Mondello—as well as a weekly “Cookies and Conversation” event. Students come by and we’ll chat or watch a movie or talk about music, and other kinds of conversations emerge from that.

The RAs and the other staff deal with “roommate disputes,” but sometimes I can help a student think creatively about issues in their academic or social lives. Most students are probably coming from relatively homogeneous communities and then suddenly they have a thousand neighbors from all over the place, not to mention their roommates. Or a student has been written up by GWPD and is terrified about what consequences will be. Or how a student might approach their parents about changing a major. Especially in the first year students might be concerned that something they could do would totally ruin their lives. But, with a few exceptions, there really isn’t anything.

The students are able to—and do—knock on my door and say, “I’d like to talk to an adult about this,” whatever the thing is. Sometimes they’re really clear that they’re not seeking advice from me; they have some ideas and just want me to be a sounding board. I am perceived as the approachable adult in the building. I’m their neighbor.

And I’m constantly learning from them. Every generation has a new take on the world. Hearing the things that they’re thinking about, the concerns they have, what they see as constraints and what they see as possibilities, that’s always shifting, and it’s helpful to me to be aware of all that when I’m teaching. I can also help colleagues understand what concerns are surfacing in the dorm, what students seem to be anxious about, and if classes are looking light I can legitimately report half the dorm is down with the Thurston Plague this week.

Something I didn’t expect was how much joy there would be with this, like when people who’ve been coming to “Cookies and Conversation” knock on the door Halloween night to show off their costumes. I had a student last week who’d been bemoaning the challenges that she had in getting a work-study job, and this week she came by and said, “I don’t want a cookie, I just want to let you know I got a job!” You get to share highlights with them. — Randi Kristensen, deputy director of GW’s Writing in the Disciplines program, assistant professor of writing and faculty-in-residence at Thurston Hall (as told to the author)

Turning Off the Music(al)

The show, Nine Stories and A Basement: A Thurston Musical, is about a girl, Mikaela, coming

back to Thurston as an RA for her senior year. On her first night back, Mikaela falls asleep and dreams her entire freshman year over again, but set in the 1960s.

At the end of that first act there’s a fire, based on the actual 1979 fire, and Mikaela is trapped in the building. At that moment she wakes up from the dream, and then has to finish her senior year—and Thurston’s last—in the present day.

The play gives us a chance to relive the Thurston of the past and some of the issues of the late ’60s, like the treatment of women on campus, and the parallels between social activism then and today. And it’s symbolic of the hardship people go through while they’re in college; the growth that’s required. It’s not going to be easy and you’re going to come out a different person. The question of the first act is, essentially: Where do I stand if everything’s burned? And then the question of the second act is: OK, I need to move forward. I have all this baggage, what am I going to leave behind, and what am I going to take with me?

The process so far has been a whirlwind, from doing a lot of the research and the writing on my own, to then getting a cast and bringing them into that process. It’s a “devised show,” which means the cast has a role in developing the characters and the story. Thurston encapsulates so many stories, and I want to make sure the cast feels like their stories are being represented.

Thurston is the only place I’ve lived on campus. I was there as a freshman, then as an RA my sophomore year. I studied abroad junior year and returned to Thurston as an RA this year. Being surrounded by people who are in such a dynamic time in their lives, I think I’ve been able to hold on to that wonderment of the world and of college a bit longer than a lot of my peers. I just get to see people doing such human things, like making friends—freshmen showing up to college and attaching onto the nearest person they find because they’re scared and in a new place, and then you see them adjusting to this new way of life.

Going into this play, I wanted it to be a place for people to celebrate Thurston, and then to let go of it.

Letting go will be something different for the people in my year: We’re going to be the first class in nearly 60 years that doesn’t get to return to Thurston for all of the memories created there. It’s going to be a totally different building inside.

It’s a complicated feeling. This is probably for the better—the building needs to be renovated—and it’s good to let go and to move on and not have something you’re attached to, to kind of hold you back. But at the same time it’s nice to have the physical marker to spur memories.

I’ve been giving alumni tours every year that I’ve been here, and I see what they experience by coming back. That gave some inspiration for the play in a lot of ways. For instance, my freshman year, I brought an alumnus from the ’60s to my room and they said, “This is it. This is the room where we would put a ladder across the alleyway between Mitchell and Thurston and the men would climb across the ladder into the all-women Thurston dorm to avoid the curfew.”

This year for alumni weekend I interviewed alumni to get more material for the show, and people came in and cried as they spoke.

This was a transformational home for so many people, and I just want to give them that space to let them breathe for a second and say: Yeah, this is an odd treasure of a place that you’re not quite sure is an actual treasure, but it did a lot and it won’t be there anymore in the same way.

I still have to finish the play, but now from home. I have a piano there and all of my recording equipment and a computer, so that’s still part of the online coursework that needs to get done, but it likely won’t be performed. That’s the unfortunate conclusion that I’m still coming to grips with. This was going to be a big thing for me in finding similar work after college.

I hate hurried goodbyes, and that’s pretty much what it’s going to be right now, both with friends and for this goodbye to Thurston. We’ll have to come back to get the rest of our stuff, so I will see the building. But this March move-out is pretty much our goodbye. — Andrew Hesbacher, CCAS ’20, majoring in international affairs and music (as told to the author)

* As the campus response to the novel coronavirus evolved, eventually keeping students off-campus and learning remotely for the rest of the spring semester, so too did Andrew Hesbacher’s plans. Instead of a musical, he made a documentary about life inside Thurston based on interviews with alumni.

The Future

Thurston Redux

For more than 50 years, Thurston Hall has played a central role in GW campus life. Thousands of relationships, stories and memories shared among members of the GW community emanate from that residence hall, which has developed a stature on campus unlike any other.

But time and significant use have taken their toll on the facility, which currently houses nearly 40 percent of GW’s first-year undergraduate students.

Reimagining this storied residence hall is a key element of the university’s strategic initiative to create a preeminent student experience. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has altered life on the GW campus dramatically.

While the safety and health of our students have always been top concerns, more than ever we recognize the need to create a place for students to call home at GW that enhances both physical and mental health. For all these reasons, the Thurston Hall renovation is a priority that will continue to move forward, the only capital project to do so in a challenging environment.

The two-year endeavor—now under way with the building scheduled to re-open in fall 2022—will offer former residents and friends of Thurston multiple opportunities to engage and contribute to its transformation.

The goal is to produce new and inviting social, academic and residential spaces for students to live and learn as well as to upgrade the building infrastructure. This will make the building more functional, sustainable and community-oriented.

There will be new three-season atrium, student lounge, and spaces with natural light feature prominently in the concept for a complete interior renovation.

The concept also includes a multi-purpose space, food service and penthouse student space offering views of the surrounding city. The hall will house roughly 825 students in doubles and singles as well as faculty-in-residence and residential life staff.

VMDO Architects, based in Charlottesville, Va., designed the renovation concept.